SEND transition planning

The summer term is upon us! Lighter evenings, hope of better weather and a diary full of teaching, sports days, residential trips and end of year celebrations! For Year 6, there's a mix of excitement about stepping into the unknown, coupled with some unease. Throughout their primary journey, staff have prepared pupils for this transition and now it is in the final stages.

Whilst this blog focuses on the transition from primary to secondary, the planning principles for transition are adaptable for any age phase. For those of you supporting transition in the early years consider exploring these blogs from the HFL Early Years Team:

- 5 Top tips for supporting smooth transitions in the Early Years | HFL Education

- Transitioning from reception: Year 1 readiness in science | HFL Education

Dr Dan Nicolls states:

Advantaged children leap confidently across these transitions, whilst disadvantaged gingerly and uncertainly step across; this is not for me.

Dr Dan Nicholls

Thoughtful transition planning between primary and secondary schools can create a seamless shift, ensuring pupils and their families feel they are moving from one safe space to another. Continuity, security, and creating a sense of belonging in the new school community are crucial for long term success, especially for those with SEND. Establishing this early could support pupil attendance, reduce the risk of emotional school-based avoidance (ESBA), and potential suspensions and exclusion.

Let’s explore some top tips on how schools can strengthen their transition plans.

Pupil voice

What if… I get lost? Get a detention? Forget my homework?

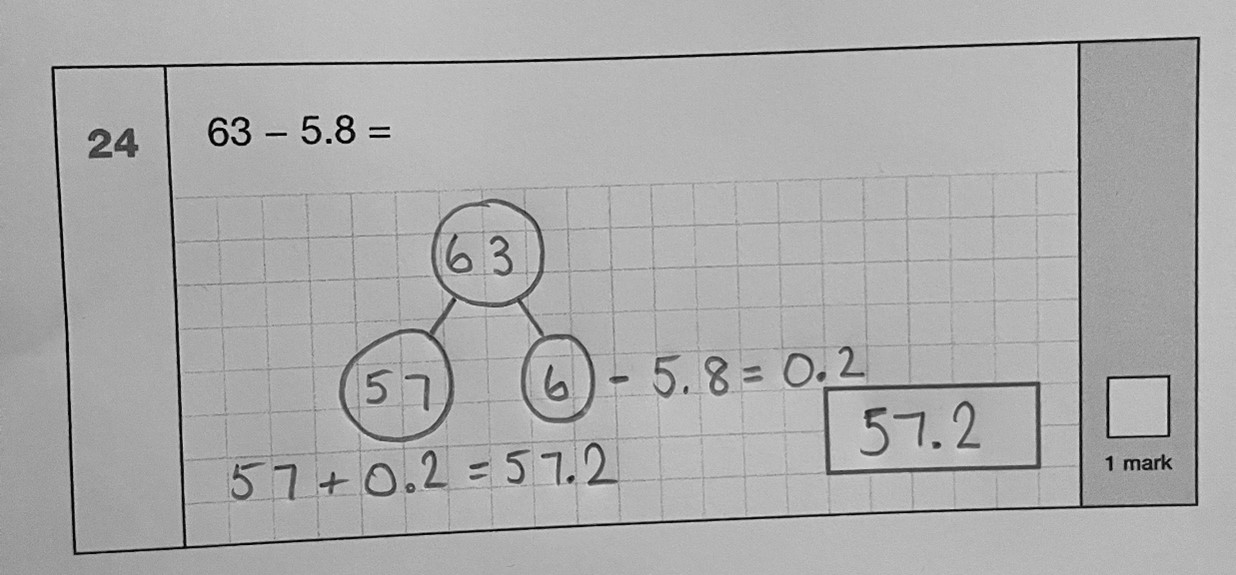

The purpose of listening to pupils is to personalise transition, share information with secondary staff and show pupils that everyday worries are normal during any change. Pupils should have opportunities to discuss their own concerns whilst also focusing on navigating unfamiliar school routines and systems.

Are the year 6 cohort given ample opportunity to ask questions about secondary school?

An ideal opportunity is when secondary staff visit their feeder primary schools. One effective approach I have used was giving pupils time to discuss, reflect and record questions with a primary staff member. In one such session, I was surprised when a group of pupils identified with social, emotional and mental health needs (SEMH), shared initial unease centred around showering after PE and putting on a tie. Not one mention of behaviour policies, homework or getting lost! The discussion uncovered concerns that were emailed to secondary staff who addressed them during their visit-many pupils commented on how approachable and responsive the secondary staff were.

Primary staff may wish to reflect on who will act as mediator and how they will share this with secondary colleagues.

Secondary schools may consider curating the information into a frequently asked question document to share with families.

Some useful tools to strengthen pupil voice work include:

- Helen Sanderson Associates: Consider the good day/bad day, perfect week documents. These person-centred tools provide information on what is working, pupil interests and can strengthen staff knowledge of pupils with SEND.

- Children’s Commissioner: A free activity pack focusing on pupil voice with worksheets and activities.

- Dr Pooky Knightsmith: A particularly useful tool to manage concerns is the If….Then…Planning tool.

- Black Sheep Press: Talking about Secondary School can be used as a visual scaffold to initiate and strengthen discussion as part of pupil voice, particularly for those with speech, language and communication needs (SLCN).

- Autism Education Trust: have provided some great templates which identify a concern and provide a free text to add in how this can be solved.

- Blob School book: a great visual to facilitate and stimulate discussions about a range of situations, such as the playground or classroom. Could be used with a class, group or individual.

Developing healthy networks

We need to be seen by our friends who serve as important attachment figures in our lives; we need to be safe with them; we need to be soothed by them; and we need to feel secure with them.

Daniel J. Seigel

Some pupils with SEND face challenges in forming and maintaining healthy relationships. Familiarity can support in establishing new friendships, but just because pupils have attended the same primary school does not automatically mean they have a positive relationship.

- How and when are primary schools sharing information about peer group support and friendships?

- How do secondary schools use this information from primary colleagues to group pupils?

- What support do both primary and secondary staff offer to pupils who are transitioning without a familiar peer? This could add an additional layer of vulnerability, particularly for pupils with SEND.

Moving from a small number of teachers in primary, to working with a larger number of adults in secondary school is a significant change. Pupils with SEND may benefit from having one key staff member who is responsible for taking an overview of how the pupil is settling in; this can be done through regular check-ins. Who will this be? A form tutor? Head of year? A specific teacher? They will build the foundations of a support system, provide feedback to the SENCO and as such may need to be involved in transition.

When working with a pupil with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), the previous setting told me they loved playing card games. I factored this in when visiting helping to quickly establish a positive relationship and included this when introducing new staff as part of enhanced transition. I created a photo book of key staff, including an image of us playing cards, which parents reported helped during periods of uncertainty during the summer holidays. Primary staff may want to use personalised photographs when discussing staff during transition discussions. I worked with one student who loved it when I asked questions about secondary staff, referring to them by name, with parents informing me it took away the unfamiliar. Another way to create connections for pupils requiring an enhanced transition, is to send an email or postcard over the summer.

For pupils with SEND it is important for secondary schools to establish positive connections with parents early on. When pupils and parents need a more bespoke transition, primary staff may wish to consider inviting the secondary school to specific meetings. Hosting at the primary school, where parents are familiar, can reduce unease and demonstrate a collaborative approach to transition.

Secondary schools should consider how communication processes are shared during transition plans.

- Who do parents communicate with and why? For parents who have a child with SEND is it directly with the SENCO?

- Is contact via email, telephone or in person? How long can parents expect before teaching staff respond to parent communication?

- When are formal meetings held each year to review provision/needs? Set expectations early on and be transparent.

Remember parents, whose children have SEND, will have experienced different journeys, and may require different levels of transition themselves. The Hertfordshire SEND Toolkit has some great practical tips to support communication with parents and there is a whole section on supporting transition.

Familiarisation with the school environment

A variety of opportunities for induction, taster days and visits between schools appear to improve institutional adjustments.

Exploring the environment enhances familiarity and one successful approach I have used involved pupils, in teams, completing a treasure hunt. Staff photographs were displayed in subject areas and pupil voice questions located the next clue. For instance, “where can you get a plaster?” (A helpful detail when year 7 pupils are breaking in new shoes!)

Many pupils with SEND benefit from visual scaffolding to embed learning and transition is no exception. Providing maps of buildings can be particularly helpful. Secondary schools could consider colour-coding by subjects or faculties for clearer visual support. One school used the colour of the subject exercise books! Sharing photographs of key areas, with pupils in them during a visit can aid familiarity, and scaffold primary staff discussion. One primary school I know well used this to practice mapping out movement from one lesson to another.

Secondary schools may need to consider if pupils with SEND will access additional support outside of the classroom. During transition activities consider

- Do they know where, when and how to access the support?

- If they need to leave a lesson, do they know the processes to achieve this? Do all staff know that this will be happening?

- How will this be factored into transition planning?

Continuity of provision

A proactive and anticipatory approach to provision can enhance transition and pupils settling into their new school.

Primary staff should think about how this can be shared with secondary settings. Do written records:

- Reflect the current level of need?

- Include information on strategies and reasonable adjustments used to support high quality teaching?

- Reflect additional support outside of the classroom, including break and lunch times?

Clear, specific, up to date documentation is particularly important to secondary schools as they often have a number of feeder primary schools.

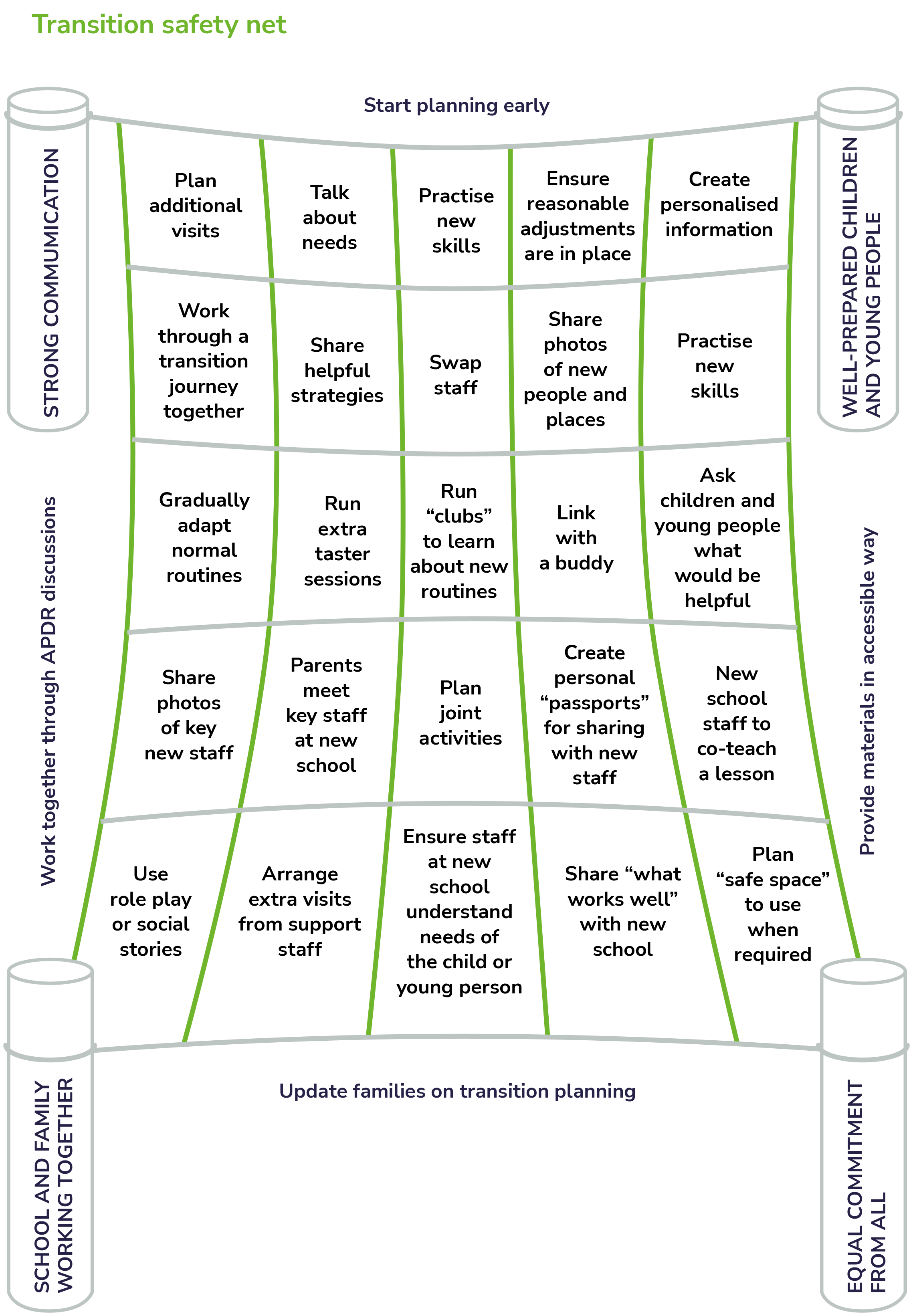

The transition safety net, within the Hertfordshire SEND Toolkit, is a great visual to support reflections.

Good quality information handed on by primary staff should assist secondary practitioners to quickly apply effective teaching strategies at a universal level, during high quality teaching, and, when required, at a more targeted level. The secondary SENCO should consider:

- How will this information be shared with all teachers to ensure suitable support from the start of the year?

- Do all staff have the skills and confidence to provide this support?

Reflections for the next year?Top of Form

As part of the transition process, it is important to review what worked well and consider this in planning for the following year. Towards the end of September, strategic schools should consider:

Primary settings | Secondary settings |

| How effective were you in gathering pupil voice and addressing concerns? | How did pupil voice enhance transition? |

| How did you communicate pupils’ needs and provision and how could it be strengthened? | How did you ensure staff understood and implemented adaptive teaching for students with SEND at the start of the year? Do staff need additional training on adaptive teaching to meet the needs of individual pupils? |

| Was the CTF (common transfer file) process in a timely manner? Who was responsible for ensuring this was completed? | What discussions would have enhanced transition information sharing? How will you achieve this? |

How did you gather feedback from parents and pupils? What did they find useful during transition? Did any school-planned events, as part of transition, inadvertently add pressure to families? Consider factors like cost, physical accessibility, and emotional impact on those unable to attend if offered during the summer holidays. | |

How do you measure success of transition? Could you link back with secondary schools in the autumn term to offer any additional settling in support? | How well have pupils settled in? How do you know? Consider how you will be forensic in this. Attendance data and behaviour logs can be early indicators but consider access to:

What does this analysis tell you and what will you do with the information? |

By reflecting on transition as a series of interactions that engender a sense of belonging and security, we will support all pupils, particularly those with SEND, to face the exciting challenges that secondary school presents. So, as you embrace the summer term consider the steps you will implement to enhance transition for the next academic year and beyond.

For further blogs on curriculum continuity during transition consider exploring the following blogs from our HFL colleagues:

- Preparing transition to secondary school…considerations for language learning

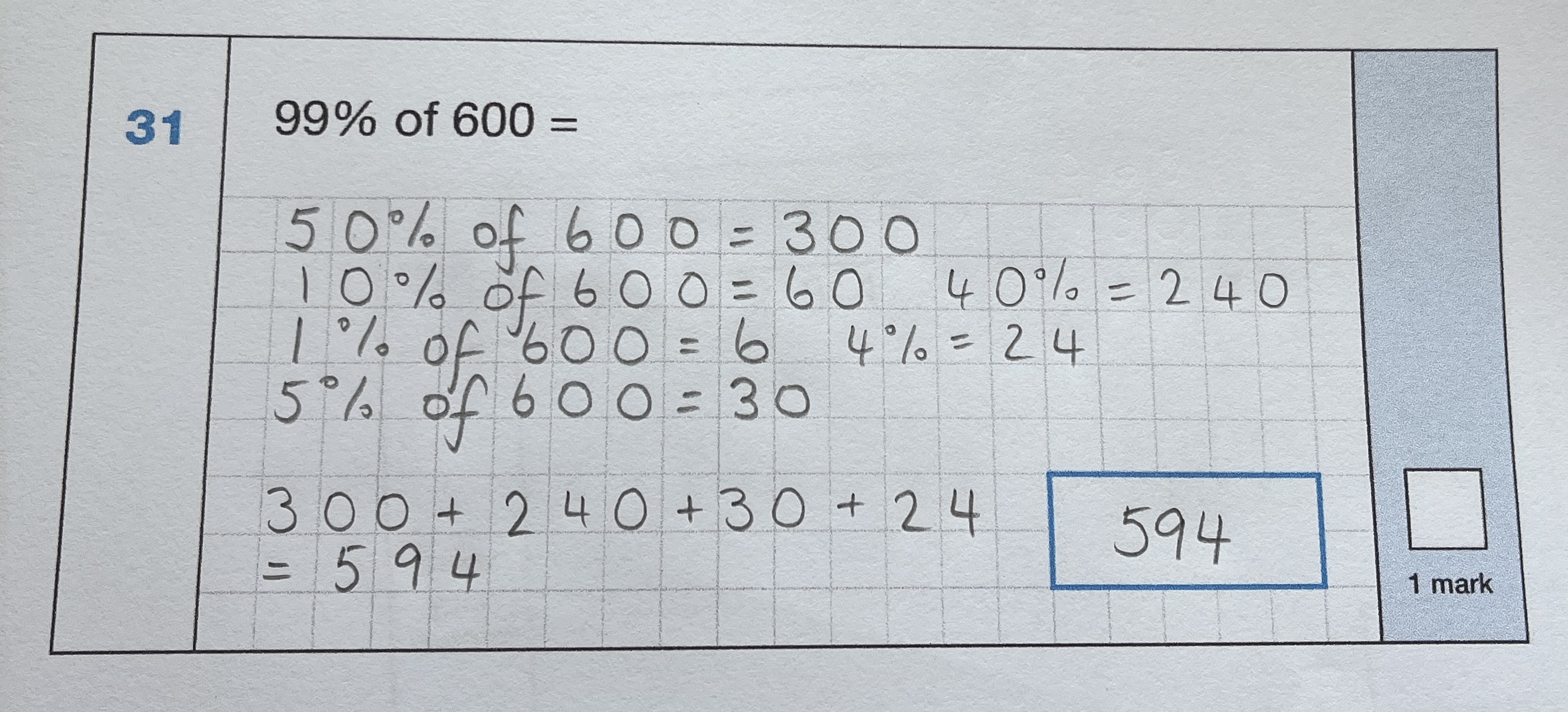

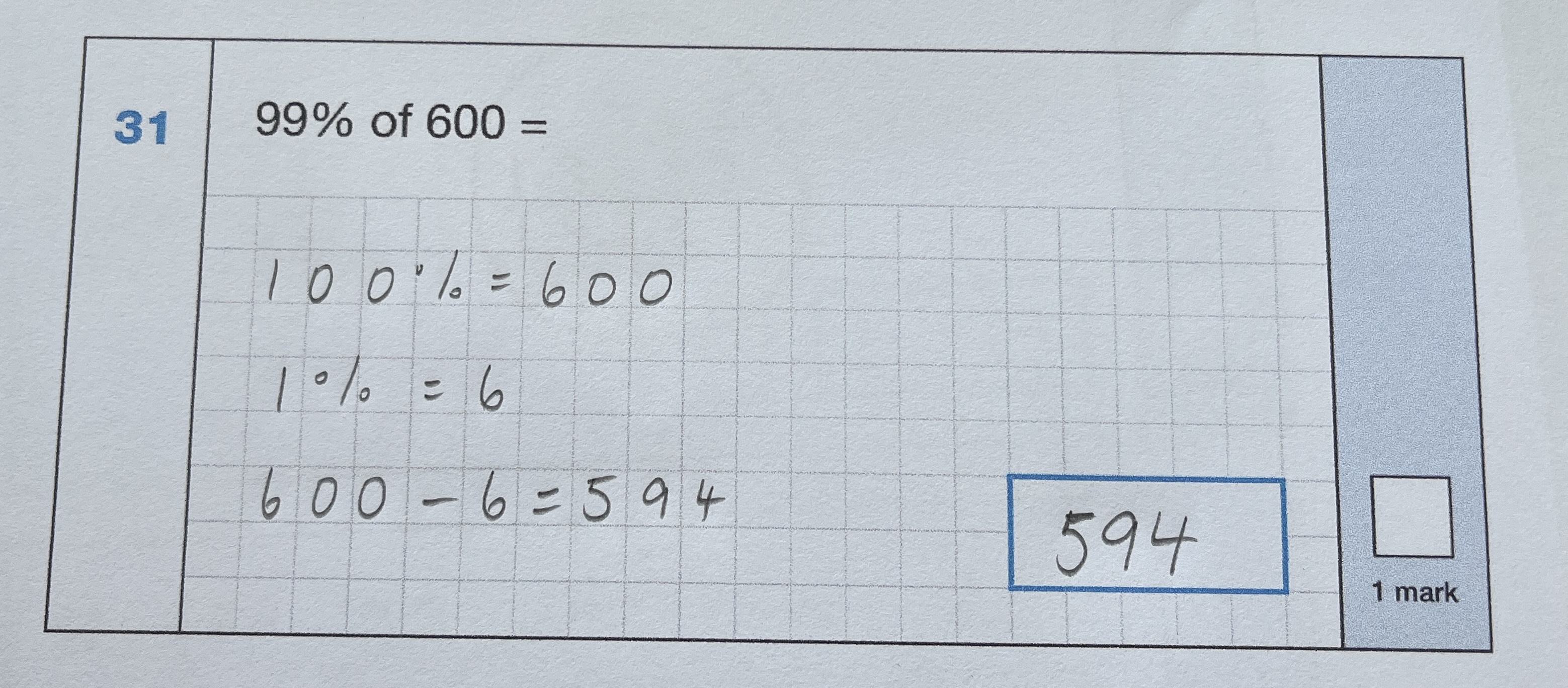

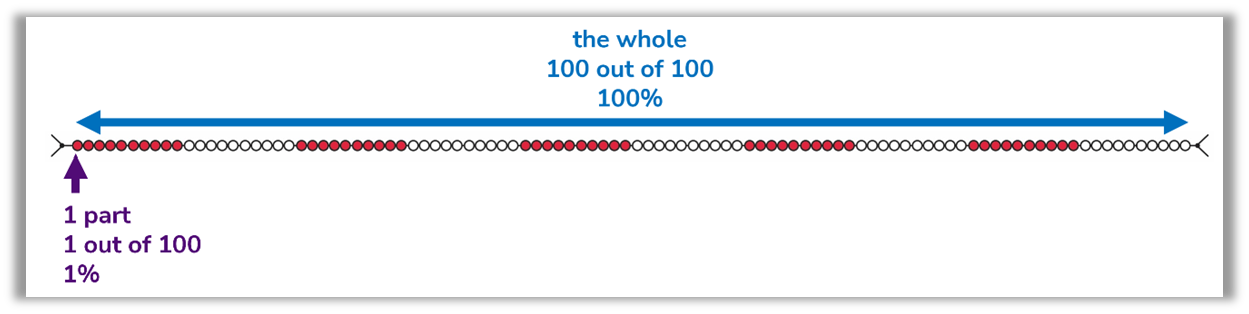

- Supporting lower attaining pupils in KS3 maths to become fluent and flexible calculators

References:

- Nicholls, Dan (December 3rd, 2023) Be Braver | heroes needed | Dan Nicholls (dannicholls1.com)

- Seigal, Daniel J. (2014) Brainstorm-the power and purpose of the teenage brain