ESSENTIALWRITING: A call for change

In a world where a series of de-personalised lesson slides can be downloaded in a single click, and where AI can script a generic model for writing, we run the risk of deskilling our most valuable assets: our teachers.

As advisers privileged to support schools throughout Hertfordshire and beyond, we frequently encounter a recurring narrative. Teachers report that many of their young writers are disengaged and unmotivated during writing lessons. Many even find the teaching of writing overwhelming or personally challenging themselves. Whether it is due to time constraints, the constant need to fill gaps from previous years, a demanding curriculum dominated by formal grammar instruction, or all of the above, we have heard it and continue to experience it first hand. Assessment data for writing also highlights the need for change.

The story continues with the very recent report from the Literacy Trust’s Literacy Survey, which explores children and young people’s writing enjoyment at school and in their free time. Sadly, it reveals that pupils’ motivation and enjoyment for writing is the lowest since 2010.

“Increasing evidence of a long-term downward trend calls for urgent action to reconnect children and young people with writing that promotes connection with creativity, self-expression and mental wellbeing.” – Literacy Trust 2024

ESSENTIALWRITING: Help is at hand!

The Primary English Team has been collaborating with school colleagues to develop and trial an innovative writing curriculum tailored for both teachers and children. This curriculum aims to enhance the knowledge, motivation, and confidence of teachers and children by exploring the craft of writing.

This close relationship with schools has provided us with valuable insight, allowing us to develop a clear philosophy with quality pedagogy and values that are built upon a strong evidence base.

The Rationale

So let us start with the why. Why Essential Writing? Why now?

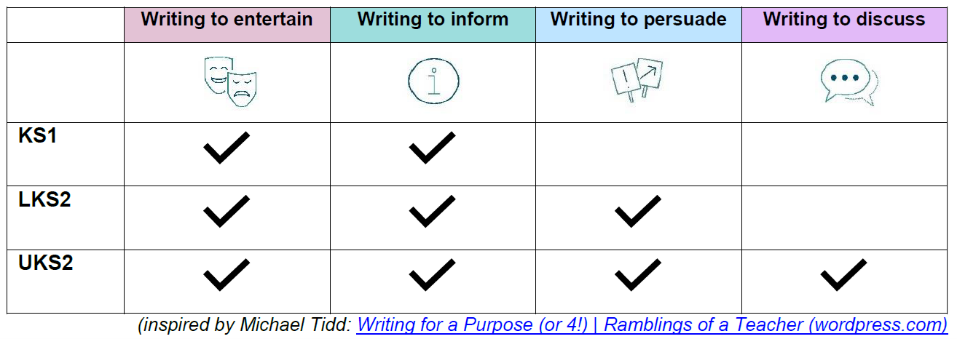

ESSENTIALWRITING is a progressively sequenced writing curriculum for years 1 to 6, that is built upon the principles of writing for authentic purpose and audience. The curriculum is designed to teach and review children’s understanding of language choices, according totheir writing purpose, across the year and in subsequent years.

Allow us to elaborate...

Why am I writing and to whom am I really writing?

As much as possible, within every unit plan, children are encouraged to write for a chosen, authentic audience and are provided with time to publish and share their writing with their intended reader(s). These authentic reasons to write, and seeing these experiences through to the very end, can drive motivation, engagement and pleasure – not to mention a real and genuine care for the writing process.

Thank you to teachers at St Paul’s Walden, Hitchin who commented that, when trialling the plans:

“Children loved writing for a real purpose and were excited to receive a response and see the impact of their writing!”

“The quality and quantity of the work has improved massively!”

Sequenced and progressive

ESSENTIALWRITING has been developed to ensure complete National Curriculum coverage from year 1 to 6. Objectives have been mapped out across the year with opportunities to review key objectives from the previous year group embedded. Objectives build sequentially over the year with deliberate emphasis and repetition of core skills that children will rely upon the most within their writing.

“Effective enactment of a progressive, sequenced curriculum, every lesson, every day, as a universal entitlement, offers far greater opportunity for all.” – Dan Nicholls

We understand the importance of a structured curriculum with high expectations for all children, and this is especially important for pupils currently experiencing disadvantage. We aim for new knowledge to seamlessly ‘stick’ to existing knowledge. This spiral curriculum is designed to introduce new concepts in manageable chunks and offer meaningful opportunities for application as children delve deeply into studying the craft of writing.

“When planning a curriculum, teachers and leaders should prioritise progression in knowledge of language and of its forms, usage, grammar and vocabulary. This knowledge, of the structures of language, can then be used by pupils across their spoken language, reading and writing.” - Research series: English, Ofsted July 2022

High-quality texts and written models

It goes without saying that this curriculum is centred around high-quality literature, and although ESSENTIALWRITING does use a wide range of engaging books, it is not a reading

curriculum. Our plans offer abundant opportunities for children to engage with texts through reading, discussion, drama and more; however, the focus is on writers having abundant opportunities to read the core texts as writers that notice the writerly craft.

The texts we have selected serve as rich inspiration, and by immersing themselves in these texts, children learn to deploy the techniques employed by authors and understand their impact on real readers. Rather than simply repeating content, a common pitfall in writing classrooms, children will now have the chance to analyse the choices writers make and the reasons behind them.

Or curriculum places a strong emphasis on the art of writing, leveraging our reading experiences to develop a deeper understanding of what constitutes effective writing. Through this approach, we aim to grow a generation of writers, who not only appreciate the craft of writing, but who also thrive in it!

Pitch-perfect!

While these diverse texts offer us a wealth of inspiration, from language models to sentence structures and idea inspiration, we acknowledge that they may not always be pitch-perfect or align with our desired success criteria. As a solution, we have developed teacher-written models tailored to each year group's programme of study. These models serve as guides, ensuring that teachers can deliver exemplar writing models that are responding to the needs and expectations of their pupils.

Oracy, drama and vocabulary development

The recent Ofsted English Subject report emphasised the significance of speaking and listening. It shared the importance of allowing children ample time to discuss their ideas before putting pencil to paper. The emphasis on oral rehearsal, reading aloud, and other opportunities to speak before, during and after writing, is woven throughout our approach. Just as we provide models for writing, teachers will also receive support in scaffolding children's spoken language and facilitating meaningful dialogue, too!

Agency

ESSENTIALWRITING deliberately builds in plenty of opportunities for children to feel agency within their writing. We know from research that this is absolutely crucial to enabling children to feel like real writers. This includes opportunities to write about what they know, what they like and what moves them.

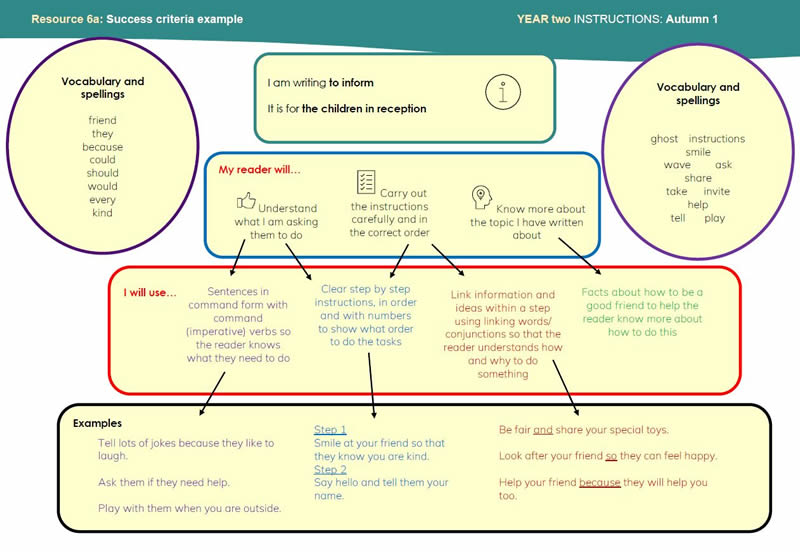

Success criteria

The development of our very own success criteria also supports children on their journey toward self-efficacy, ownership and how their own language, grammar and structural choices can impact their reader.

To support teachers and children to connect all writing choices to the intended effect on the reader all ESSENTIALWRITING units contain examples of Pyramid Success Criteria. The pyramid is designed to show how all decisions are informed by purpose and audience and how the writer wants their reader to think, feel or understand something in a particular way. These success criteria are built over the course of the unit and referred to whilst the children are composing their final written outcome.

Personal, adaptive and responsive

At the beginning of this blog we explored the potential deskilling of our wonderful teachers as a result of technological advances, pre-made resources and lesson plans.

You may be thinking, “Well isn’t ESSENTIALWRITING doing just that?”

Yes, Essential Writing is well-resourced, fully planned and sequenced but its true strength lies in empowering teachers with a sense of their own agency. Our lesson plans are designed to directly address teachers, offering guidance on how to respond to their pupils’ learning in real-time and make necessary adjustments as the learning progresses. We provide ongoing support to help teachers continually assess and address the strengths and needs of their children, guiding them in adapting their teaching accordingly.

Now, more than ever, the teaching of writing demands significant change. We firmly believe that by implementing the right curriculum, employing effective pedagogy, and prioritising the factors that we know motivate children to write, we can usher in a transformational shift.

Similar to the process of writing itself, this is a journey—one we hope you will embark on with us!

Join us today!

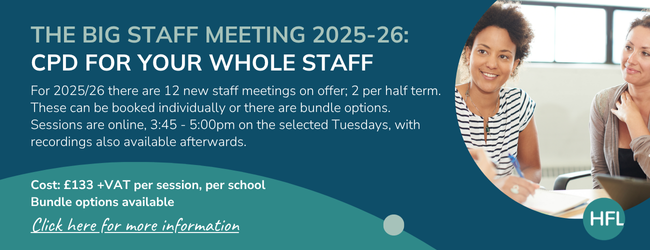

ESSENTIALWRITING subscription packages are available to purchase now! Explore the platform navigation and begin to use resources, ready for the new academic year!

Follow us on social media for more information or sign up today to be the first to hear announcements about ESSENTIALWRITING.

We are delighted to announce that HFL Education’s ESSENTIALWRITING is now live and available to purchase.

We are delighted to announce that HFL Education’s ESSENTIALWRITING is now live and available to purchase.