Assessing confidence

Further reflection on this as a generic issue, not only in Mastery Readiness schools but also within schools that I support through my advisory role, led me to ask myself the question, ‘How do you effectively assess children's confidence?’.

In attempting to answer it, I revisited part of the Primary Maths Specialist Teacher Programme (MAST) that I attended at the University of Brighton and the use of the HFL Education Diagnostic Assessments.

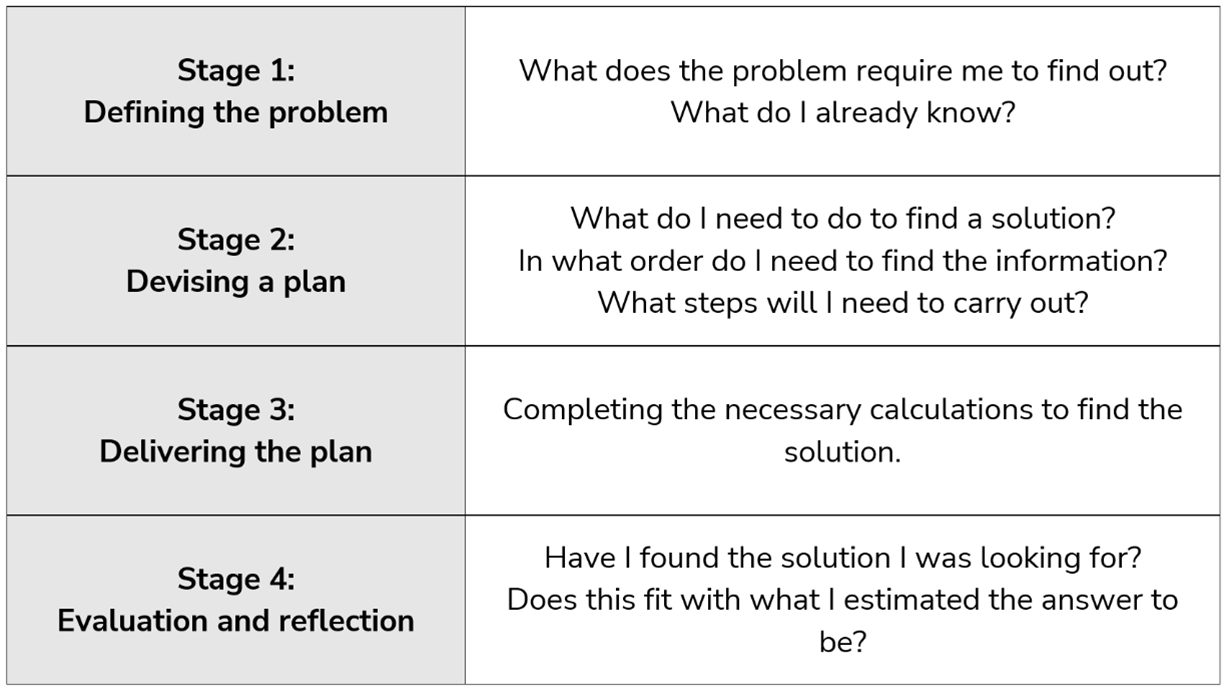

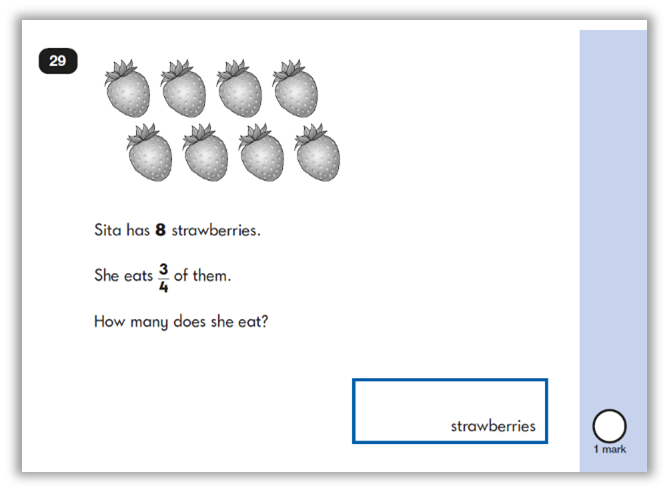

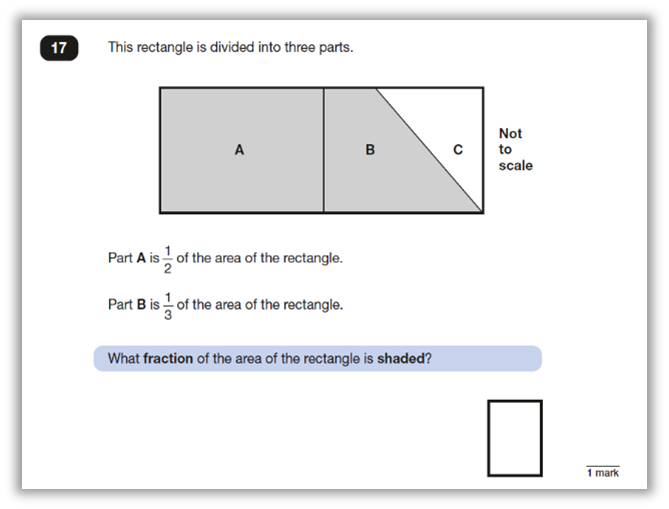

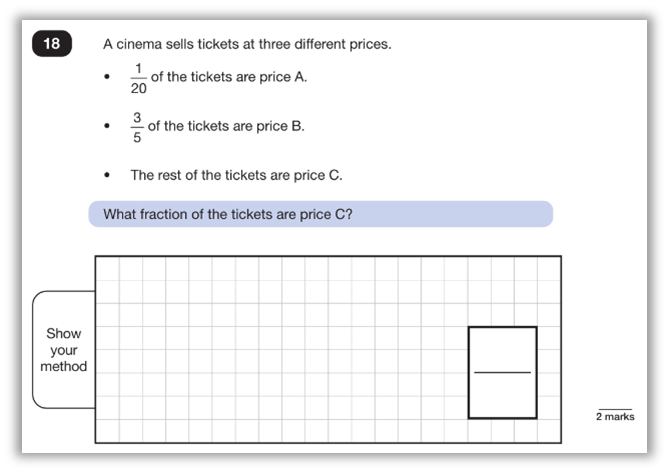

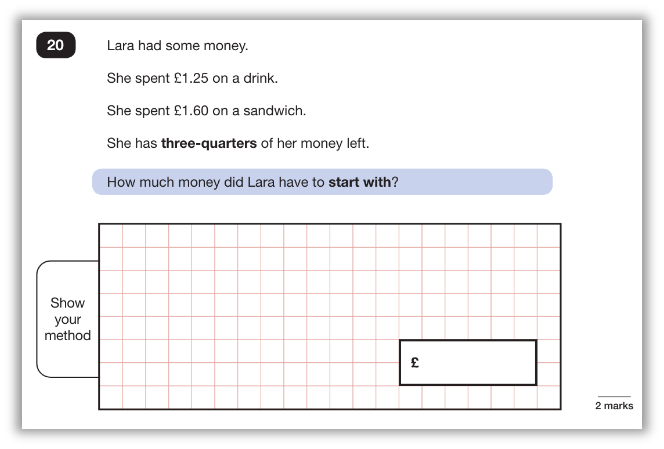

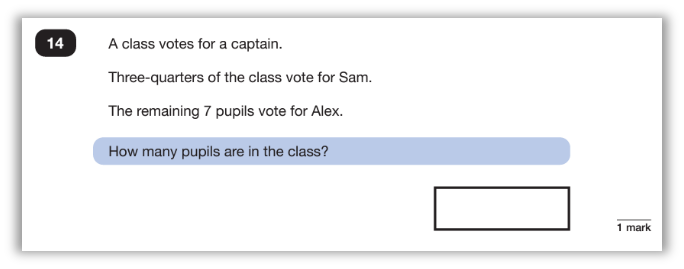

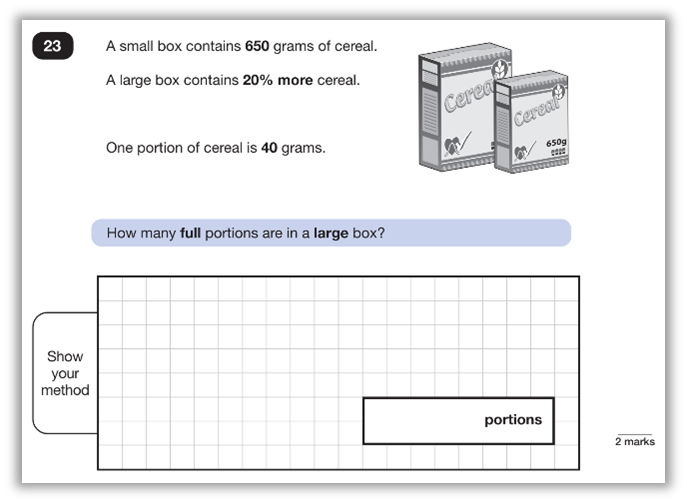

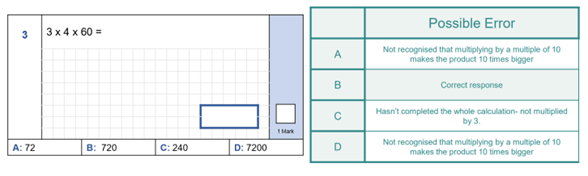

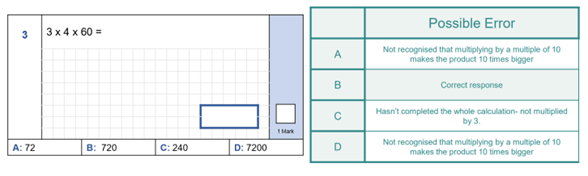

The universal rationale with both is the use of ‘Audit Questions’ for assessment of the children’s understanding; any misconceptions that they might have and any errors that they might make. Here is an example from the HFL Education Year 6 maths gap finder SATs preparation toolkit:

As you can see, the questions have carefully designed multiple-choice answers linked to common errors. The ‘possible error’ guidance then enables teachers to conduct efficient question-level analysis to guide subsequent teaching.

To focus attention on the children’s confidence, linked to effective research, I created a rationale and steps in an assessment procedure:

Rationale: The process needs to be based on both quantitative research (by analysing arithmetical outcomes) and qualitative research (through analysis of Pupil Voice scenarios) and can be achieved by working in one-to-one situations or with small groups of children who are around the same level of understanding, as assessed in lessons. Analysis of the individual children’s responses are key in achieving appropriate outcomes.

Step One: Ask the children to look at an arithmetic question and ‘rag-rate’ it regarding their confidence to answer it

- Green for definitely yes

- Amber for maybe or slightly unsure

- Red for definitely not.

Highlighter pens could be used, or the children mark the question with ‘R’ or ‘A’ or ‘G’.

Step Two: Analyse the children’s responses verbally by asking them to elaborate on their choices and unpicking both their replies and any gaps in their understanding/confidence.

Step Three: Ask them to try to answer the question and apply support/modelling of key concepts with children who are ‘red’ based on the previous step.

Step Four: Ask the children how confident they are in their answers and to revisit the rag-rating and change it, if necessary, based on their actions in the process.

Step Five: Carry out teacher intervention processes regarding any misconceptions. Move on to another question and repeat the process. Plan future teaching.

Outcomes

I carried out this process in another Mastery Readiness School, St John the Baptist CE VA Primary School in Great Amwell, Ware where I have worked with Lydia Hunt, the Headteacher, and Louise Gooderidge, the Leading Teacher.

The question shown earlier (3 x 4 x 60) was included in a range of questions that were answered by groups of four children in Year 6 who were deemed to be close to Age Related Expectations but were not confident in their approaches.

There were a range of responses given by the children, including:

- I thought it was amber but then when I looked closer, I realised that I could do it easily, so I changed it to green.

- I thought it was red but then the teacher allowed me to realise that it was actually amber for me, and I could do it with some help.

- I knew it was green, but I made a silly error in my multiplication.

- I put it as amber because I do not know my twelve times table.

- I thought that you just added zeros but now I know that you are actually multiplying by ten.

- Because there were two digits, I multiplied by one hundred.

- I forgot to multiply by ten because sixty is six times ten.

Impact

In all the questions that were explored, all the possible errors were discussed in depth and linked to key mathematical concepts. This was especially regarding the children understanding the powers of 10 and how the product can be 10 times bigger.

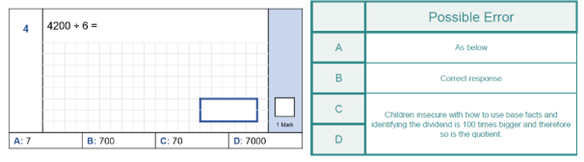

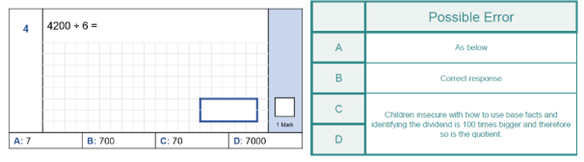

This was also linked to inverse operations regarding dividends and quotients:

The use of zero as a placeholder was also explored in depth, especially with regards to the implications for working with decimals.

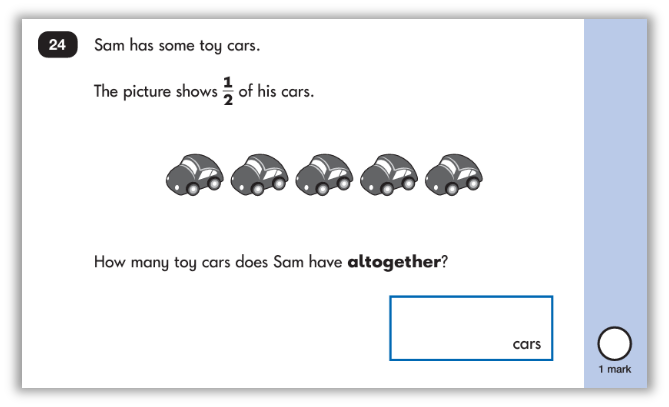

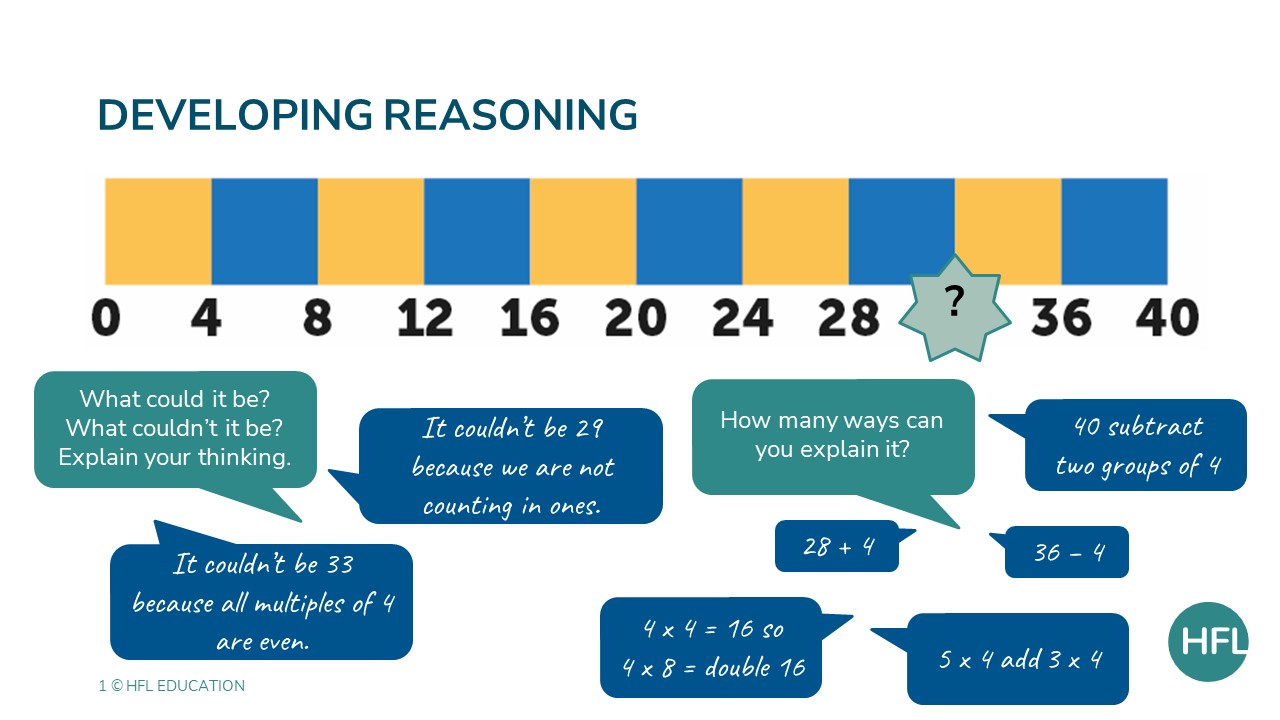

As time was spent in analysing the concepts, the children also had opportunities to be flexible in their approach, and to look at the questions without the initial thought of carrying out a formal calculation if it was not needed.

With the 4200 ÷ 6 question, the children did not immediately link it to times tables.

The specific key concepts were analysed for how effective pedagogy would enhance the outcomes and the idea of children as fluent and flexible calculators was explored.

Future teaching and intervention sessions were planned by Louise and instigated over time. This had significant impact and she asserted that children’s confidence had risen and their arithmetic scores had increased dramatically recently in practice tests.

Conclusion

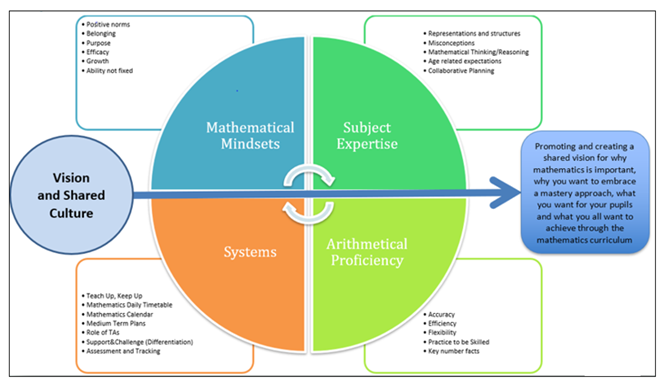

In the initial Mastery Readiness workshop, the question of, ‘Why does a school need a vision?’ is explored in depth and related to two quotes by Nelson Mandela:

‘Vision without action is just a dream, action without vision just passes the time, and vision with action can change the world.’

‘It’s easy to become distracted doing things that are related to, but not core to our vision. The whirlwind of being busy can deceptively lead us to believe we are achieving something.’

I believe that it is imperative to have an apparent, personalised and informed vision of what a school aspires to achieve, with a clear focus on outcomes for children; and what that looks like in practice.

Subsequent analysis can produce identified actions and associated outcomes that are proactively monitored for effectiveness and adapted as necessary.

Within that process, it is imperative that the vision is the main ‘driver’ (and does not just become wallpaper) with the key questions of ‘What does it ‘actually’ look like in action - as a continuum?’ and ‘What is the impact?’ with ‘How do you know?’

We are delighted to announce that HFL Education’s ESSENTIALMATHS V2.0 is now live and available to purchase.

We are delighted to announce that HFL Education’s ESSENTIALMATHS V2.0 is now live and available to purchase.