Sitting down to write can be daunting. There’s a blank screen in front of us, a few ideas in our heads, and the impetus to write. We note down a plan, a general structure, and ideas begin to blossom but tying them together takes time. We have the pleasure and privilege of reading lots of blogs, so we know why they’re written, and what makes them enjoyable to read. Yet, it’s not always easy to marry those things together to get to the finished product. Ideas bounce around our heads, words and phrases appear in our mind, but it takes care, motivation, and the many steps of the writing process to get to the publishable result.

We place writing demands on children every day in school. It’s a hugely complex and demanding skill: ‘Children need to coordinate several different processes. For instance, children need to work out what they want to communicate and how, handwrite or type accurately, regulate their own thoughts and behaviour, and monitor their work.’ (EEF, Improving Literacy in KS2, p. 28)

Not only this but writing places great demands on our emotional resources alongside the cognitive demands. To do something so demanding, we need to feel that writing is a worthwhile pursuit – that we are motivated, volitional, autonomous and confident writers. If we’re going to leave a little piece of ourselves on the page, an insight into our identity for scrutiny, then there had better be good reason to do so. As Young & Ferguson state: ‘Emotionally healthy young writers are able to produce better texts because they have secure writerly knowledge (cognitive resources) to draw on, they know how to manage the processes involved in writing, and they can use and apply a variety of writerly techniques’ (Young & Ferguson, The Science of Teaching Primary Writing, p. 13).

We know that there has been a stark decline in the percentage of children and young people in the UK who are volitional writers. In June 2023, the National Literacy Trust produced results from their latest survey which showed that only 34.6% of children and young people aged between 8-18 enjoyed writing in their free time. At the time of writing, figures from the latest end-of-KS2 data for writing are yet to be released, but in 2022, 69% of pupils met the expected standard in writing, down from 78% in 2019. Some people might blame the impact of Covid for these statistics, which would be undeniable, but is there a bigger picture here? Since 2016, children choosing to write in their free time has been in a steady decline - from the peak of 50.7% (in 2016) with a 16.1% drop to where we are now.

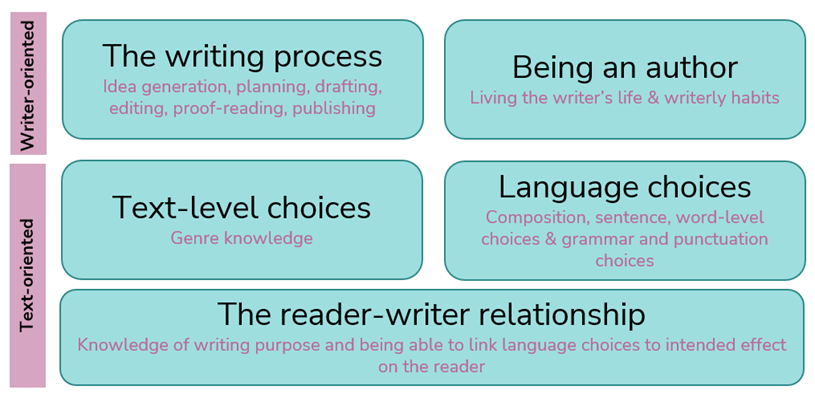

Despite these gloomy figures, there is hope. An increasing demand for research-informed writing teaching is blossoming, led by the clarion call of Ross Young & Felicity Ferguson at The Writing for Pleasure Centre and other hugely influential academic researchers. In a recent article, written by Debra Myhill, Teresa Cremin and Lucy Oliver, entitled ‘Writing as Craft: Reconsidering Teacher Subject Content Knowledge for Teaching Writing’, the authors suggest that there is a distinct lack of empirical evidence concerning what constitutes teacher subject knowledge for writing. They propose reframing writing as a ‘craft’ rather than a subject and suggest five key themes of writing craft knowledge (the pink writing underneath is our own, the headings are suggested within the article):

Whilst we cannot go into details for all of these areas, let’s briefly focus on the three text-oriented themes – (i) the reader-writer relationship; (ii) language choices and (iii) text-level choices. In other words, and this is a huge simplification (but needs must): how can we write effectively based on our purpose for writing and how we want our reader to feel/think/do/understand, and what language and text choices can we select to do this?

The National Curriculum currently does not help teachers to understand the craft of writing. Statements such as: ‘In narratives, create characters, settings and plot’ offer up no guidance as to how a writer would go about bringing a character to life, or the techniques writers use to construct a vivid setting. This lack of direction often leads to writing being skewed towards box-ticking of grammar terms and punctuation (sometimes leaving out the craft of composition entirely). The authentic craft of writing therefore, in many classrooms, remains a mystery to all involved.

However, within its aims, the National Curriculum does emphasise the importance of an awareness of purpose and audience: ‘Effective composition involves forming, articulating and communicating ideas, and then organising them coherently for a reader. This requires clarity, awareness of the audience, purpose and context, and an increasingly wide knowledge of vocabulary and grammar.’ (The National Curriculum in England: Key Stages 1 and 2 Framework Document, 2013, p. 15)

There are various suggestions for a range of writing purposes, but we could broadly categorise them as: (i) writing to entertain, (ii) to inform, (iii) to persuade and (iv) to discuss. Michael Tidd has previously blogged about his approach to devising a writing curriculum using four writing purposes here: Writing for a Purpose (or 4!) | Ramblings of a Teacher (wordpress.com). Of course, these can overlap, but there is usually an overriding one at play. Carefully constructed writing curriculums should support children in building understanding of writing for different purposes, help them to connect with their audience as a writer, and provide them with opportunities to make choices about their writing.

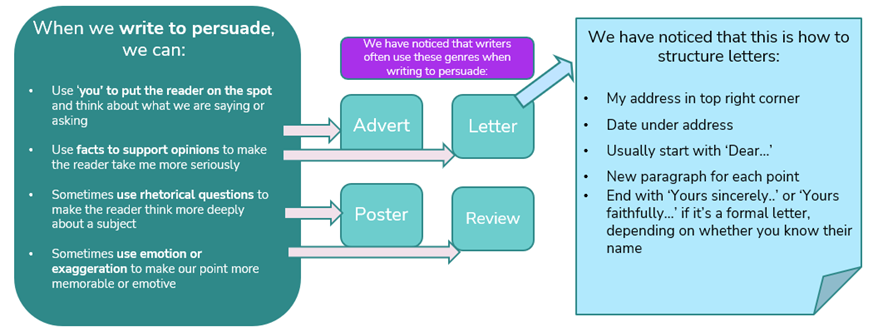

When we start to notice that writers tend to use similar writerly techniques according to their writing purpose, we can start to build writing schemas alongside a developing understanding of genre knowledge. In this example, children start to understand the language choices they could make when writing to persuade, which could be used within any of the genres listed below. Any language choices, and therefore success criteria, that the children are invited to use can therefore remain the same; their knowledge of purpose can be retained and revisited whilst learning about new or alternative text-types:

Thus, curriculum design should be carefully crafted to allow children to recognise that their language choices do not exist in a vacuum, and they can return to their knowledge of writing purpose to transfer this into different contexts (such as a variety of genres) and make links to any new learning - not only within English lessons but across the curriculum.

Of course, we need to combine an understanding of both the cognitive and emotional demands that are placed on children when they are learning to write. Both domains must inform our decisions when creating any sort of writing curriculum with schools. We must include children in the decision-making concerning their writing – making writing an enjoyable experience for them along with feeling a sense of satisfaction in their own high-quality creations (Young & Ferguson, 2021). And we also need to empower teachers to feel that they are authentic writers too, who can teach writing well with enjoyment and confidence.

If you are in a position where you would like to find out more about our ever-evolving thinking when it comes to writing teaching, and would like to receive support to develop an effective writing curriculum, then do come along to our training in September. The training will support you to:

- investigate the most effective evidence-based practices regarding writing teaching;

- consider whole school long-term planning for writing and evaluate existing provision;

- personalise writing schemes to ensure they meet the needs of the school;

- develop confidence in supporting pupils to progress in their writing attainment and enjoyment.