How time flies! It feels like only yesterday that Ellen shared her fantastic blog about the power of poetry in the classroom ahead of last year’s National Poetry Day. Packed full of teaching strategies for both the reading and writing of poetry, it also includes lots of recommended poets and text recommendations to help you on your journey to becoming an inspiring teacher of poetry – do check it out!

Engaging with poetry - through reading, writing, listening, and performing – is a valuable way to nurture children's language development, emotional expression, creativity, imagination, and cultural awareness.

“See it and live it. Look at it, touch it, smell it, listen to it, turn yourself into it. When you do this, the words look after themselves, like magic.”

Poetry in the Making’ by Ted Hughes

Poetry does indeed possess an enchanting quality. It has the power to inspire even the most reluctant writer, offering a sense of freedom with its limitless nature and lack of strict rules. For a child who feels overwhelmed by writing, poetry can provide a refreshing escape and a powerful outlet for self-expression, too!

Of course, not every child will immediately connect with poetry, and that's perfectly fine. It often takes time for both children and teachers to discover its joy. As a child, I was captivated by poetry from the moment I had the privilege of watching Michael Rosen perform in assembly when I was around only 6-years old. I eagerly read, wrote, and performed poetry for anyone willing to listen. However, my enthusiasm waned when I first began teaching, as I felt unsure of where to begin.

With a well-planned curriculum, high-quality texts, and a class full of eager learners, I quickly found my footing as a poetry teacher. Since then, there’s been no turning back, and now I burst into spontaneous rhyme at every opportunity...

Narrative tales or rhymes that catch,

Riddles to solve, or raps with an edge,

Limericks, haikus, nonsense, and lists,

Acrostics, shapes where creativity twists.

Ballads that sing, sonnets so fine,

Cinquains with rhythm, each word in line,

No matter the style, no matter the tone,

There's a poem, a poet, a verse for everyone!

... now that is out of my system, we hope this blog inspires you to plant the seed of poetry in your classrooms, allowing it to grow into a flourishing tree, with countless ‘poetrees’ blooming throughout your school.

Where to begin?

National Poetry Day offers a fantastic opportunity to begin showcasing the joy poetry can bring. This year, National Poetry Day will take place on Thursday 3rd October. This year's theme is ‘counting,’ and the Forward Arts Foundation website provides a wealth of resources, poems, and classroom recommendations. It’s an excellent way to kick off the poetry year and spark a lasting interest in poetry among pupils.

To prevent poetry from becoming a ‘one-day-a-year’ event, here are some of our favourite strategies to raise the profile of poetry so children can reap its rewards year-round.

Read and reflect

Layers of meaning require layers of reading. Head back over to Ellen’s blog, The Power of Poetry in the Primary Classroom, which explores why poetry should be read (and re-read) in layers. Learn how this can be incorporated into guided reading lessons and accomplished effectively using a range of easy-to-implement classroom strategies, where any child can contribute – low stakes, high impact, immense joy!

In this useful blog, Poetry in primary schools – how to build an effective curriculum, Alison Dawkins also shares how to plan your own poetry curriculum, including which poems you may wish to choose for your class.

Do your pupils have a chance to choose, read and chat about poetry? Continue reading to learn more…

Immerse

It’s helpful to create an environment that reinforces poetry as something of great value. Our classroom environment should be an extension of our teaching. Keep children enthusiastic about poetry by:

- maintaining an engaging, accessible, and diverse poetry area, featuring a range of poets and poetry books.

- encouraging children to talk about poetry in informal, social settings, making it an authentic part of their interactions and fostering a genuine interest.

- displaying poems—both the children’s and your own—around the school.

- exploring and sharing best practice! Head over to Open University’s Poetry Archives for examples of effective classroom practice.

Listen

One of the most effective ways to engage children with poetry is by exposing them to the rhythm and diversity of a wide range of poems and poets. Experiencing the flow of different poetic styles helps children to connect more deeply with poetry and the poets themselves. Do your children hear you, as their teacher, read poetry aloud? Do they see your enthusiasm and passion for the subject? Your attitude to teaching poetry can significantly influence how your pupils perceive and engage with it.

In today’s technological age, we have the advantage of accessing poems as they were meant to be heard—read and performed by the poets themselves. With numerous videos and audio clips available online, children can listen to a variety of voices and styles, which can inspire them to create and perform their own poetry. Useful resources include the CLPE, Book Trust’s Poetry Prompts, BBC Teach, Poetry By Heart, and other online platforms featuring poets like Joseph Coelho, Valerie Bloom, Matt Goodfellow, Janet Wong, Grace Nichols, Karl Nova, Nikita Gill and so many more!

Read aloud and perform

“ I think poetry should be alive. You should be able to dance to it.” – Benjamin Zephaniah

Poems are often crafted to be read aloud and dramatised, creating an immersive experience much like music. When children engage with poetry in this way, they don't just hear the words—they feel them. The rhythm of each line, the variations in pitch and tone, and the repetition of rich language help children internalise the poem. This helps children to not only understand the poem but also to derive meaning from it.

So, how can we incorporate this day-to-day?

- Fit it in whenever you can! One of the best things about poetry is that there are poems perfect for even the briefest moments of the school day. Send your children home with a rhyme to remember or greet them in the morning with something thought-provoking.

- Freeze-frame, conscience alley, thought-tracking, performing in role – the list goes on. Whatever the strategy, poetry can be explored and presented effectively through drama and movement. Try incorporating the two across the curriculum or as a standalone lesson for full impact. Patrice Baldwin explains more about how teachers can use drama to connect their pupils with poetry.

- Memorising rhymes and poems offers many benefits, including enhancing memory, language development, and mindfulness (see this article for further insight into the benefits of learning poetry off by heart). The process also fosters a strong emotional connection to language and brings a sense of accomplishment and joy once they master a poem!

- Organisations like ‘Poetry by Heart’ often host inspiring competitions, where children choose a poem, learn it by heart, and perform it aloud. You can incorporate this into your routine or by organising a poetry event locally or in school. Give children ample time to practise in a safe and supportive environment before performing to larger audiences.

- Poetry Cafés at lunchtime or after-school are a fantastic way to create a relaxed environment, where children can share their poetry and are perfect for those who are building their confidence in performing or for those who simply love poetry.

Compose (to write or not to write?)

For those who have recently joined our ESSENTIALWRITING journey, you're in for an exciting experience! Our poetry units are carefully designed not just to immerse children in the art of reading poetry but to also provide them with abundant opportunities to write and perform their own pieces. If you aren’t subscribed, you may like to try out this sample poetry plan for Year 5, based on the poetry of Karl Nova.

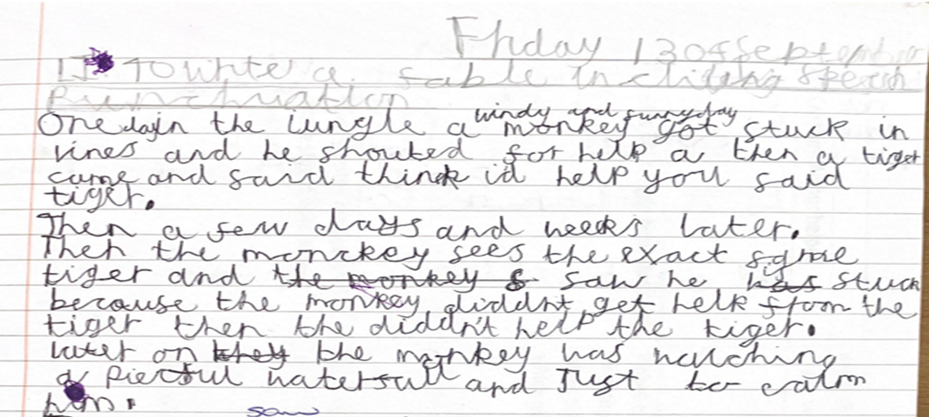

For some children, particularly those who find the act of writing itself challenging, the prospect of picking up a pencil can feel daunting. Our goal is to inspire such a love for poetry through reading and immersion that even the most reluctant writers will be eager to try their hand at creating their own poems. However, we also recognize the importance of offering non-writing forms of poetry creation, which can serve as a gentle introduction to the world of poetry without the pressure of transcription. Children may wish to try ‘blackout poetry’, ‘cut and stick’ poetry, or use digital tools to create shape poems, photo poems, or even film poems, blending language and poetic devices with visual or digital imagery.

Collaborate

Here are some effective strategies to share poetry and make it a meaningful part of your classroom culture:

- Invite both well-known and emerging poets into school for workshops and presentations

- Encourage the sharing of poetry across different year groups

- Become a poet-teacher and embody the role of a poet yourself

- Michael Rosen’s ‘Long and Short’ strategy: this is a fantastic way to encourage collaboration! Get children gathering words and phrases in small groups. Some children will act as ‘longs’, crafting longer, more detailed phrases, while others are the ‘shorts’, generating short, punchy words related to the topic. This collaborative method helps pupils engage deeply with language and fosters a sense of teamwork.

- PARK (Poetry as a Random Act of Kindness): Before joining the HFL Education team, year 6 pupils in my school wrote short poems filled with positive affirmations and distributed them randomly to others. By the end of the week, every child had either received a poem or written one for someone else, creating a ripple effect of kindness and poetic expression.

Poetry for All

The poetic devices associated with poetry can sometimes deter teachers from sharing them with all children. However, poetry offers a wealth of benefits that make it an invaluable tool in the classroom, including for children with SEND, EAL, or other needs.

Poetry has been shown to enhance children's emotional literacy, vocabulary, foster self-expression, stimulate critical thinking and imagination, and provide rich opportunities for social interaction (see the National Literacy Trust’s Children and Young People’s Engagement with Poetry survey). For all children, poetry can be a gateway to a lifelong love of reading, a deeper appreciation of language, and a newfound confidence in self-expression.

Speaking of inspiring poets and impeccable communicators… why not join us out our ‘Powerful Pedagogy: Say It, Write It, Read It’ conference where we have the honour of welcoming the one and only Valerie Bloom, amongst others!

ESSENTIALMATHS V2.0 has been shortlisted in the maths category. The curriculum was developed to provide an engaging and comprehensive maths scheme, supporting teachers in delivering a top-quality education. The programme allows educators to easily identify and address gaps in a child’s understanding, and the carefully crafted single and mixed-age learning sequences guide students through a small-step progression aligned with the maths national curriculum from Reception to Year 6.

ESSENTIALMATHS V2.0 has been shortlisted in the maths category. The curriculum was developed to provide an engaging and comprehensive maths scheme, supporting teachers in delivering a top-quality education. The programme allows educators to easily identify and address gaps in a child’s understanding, and the carefully crafted single and mixed-age learning sequences guide students through a small-step progression aligned with the maths national curriculum from Reception to Year 6. Our EYFS Induction e-learning programme has also been shortlisted for the 2024 Teach Early Years Awards in the CPD (Continuing Professional Development) Category. This innovative, four-part, self-paced e-learning induction programme is designed to support practitioners who are new or returning to early years on their induction journey. By focusing on critical aspects of child development and early learning, the EYFS Induction programme ensures that educators are well-prepared to create nurturing and effective learning environments for young children.

Our EYFS Induction e-learning programme has also been shortlisted for the 2024 Teach Early Years Awards in the CPD (Continuing Professional Development) Category. This innovative, four-part, self-paced e-learning induction programme is designed to support practitioners who are new or returning to early years on their induction journey. By focusing on critical aspects of child development and early learning, the EYFS Induction programme ensures that educators are well-prepared to create nurturing and effective learning environments for young children.