In the recent ‘Poetry in Primary Schools’ 2023 report, published by the CLPE and Macmillan, based on a survey of nearly 500 teachers, “only 38% of those felt confident about planning units of work focussed on poetry. Many cited that they felt they didn’t have enough knowledge about poetry or experience of teaching it to do so. There was a significant link to a lack of training and development in this area of literacy” (CLPE/ Macmillan, 2023). With National Poetry Day just around the corner, this blog aims to provide some support and advice for teachers to ease any anxiety and instead experience the joy of using poetry in the classroom.

Michael Rosen states in his excellent What is Poetry? (2016) that: “Poetry belongs to all of us; everyone can read poems, make up poems or share poems with others.” We might tend to shy away from poetry if we feel it is too demanding or difficult for children to access, but removing any notion that a reaction to a poem is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ can alleviate that concern. One of the greatest things about writing poetry is that, depending on the form you are using, there doesn’t have to be any rules. Of course, there are often a lot of clever things going on in a poem (see ‘poetic devices’ below, for example) but poetry is where we can encounter or write about the things that are important, fun, silly or difficult about life without worrying about the norm of writing conventions. For children, many of whom are very anxious about getting things ‘wrong’ in their reading and writing, this can be entirely freeing and empowering.

There are a few useful routes into enjoying and responding to poetry, some of which we shall highlight below.

Listening to, reading and re-reading poetry

Something to always bear in mind when reading any poem – it needs to be read aloud. And once that has happened, it needs to be read again (and again, etc). Sounds, rhythm and phrasing are especially important in poetry, so hearing any poem read aloud is likely to have been the intention of the poet. Reading poems is a brilliant way to practise fluency – for example, through echo reading, paired or assisted reading and choral reading. To quote Michael Rosen again, “Every time I’ve ever read a poem – even one of my own – reading it more than once starts to open doors for me. It’s as if I walk into another room and find a bit more of it each time. That’s because poems often say things in strange ways. Reading them several times means that they become less strange” (2016, p. 85-86).

Building to a performance of the poem really helps to motivate children to read it aloud repeatedly. Seeing poets performing poetry ‘can offer children a unique sense of feeling and engagement with a poem’ (CLPE, 2020, p. 45). The CLPE’s website and the Children’s Poetry Archive have a wealth of videos and audio recordings that can be used in the classroom.

We should be offering poetry within the classroom (see section below, ‘Choosing Poetry’) as something that children will choose to pick up and read for themselves. We should aim to read poetry aloud regularly just to enjoy and hear the language at play, informally chatting about what we might think about it and our responses to it. We might be tempted to delve straight into an analysis of a poem but try to resist this in favour of allowing children the time to consider their own reactions and emotive responses first.

There will also be occasions when you, as a teacher, will want to go into greater depth with reading poetry in a more structured way. Here is an example of how you might do this (suitable for end of KS1 upwards), using Doug Lemov et al’s ‘Reading Reconsidered’ development of layered reading. The old adage ‘the more you look, the more you find’ is entirely relevant to reading poetry. Between every re-read, it is crucial to ask children to share their thoughts and generate discussion with the class about their understanding of the poem – based on what they know from a literal reading (e.g. What does that word mean? What is happening here?) but also what they think the poem or the poet could be saying to us, as readers. We can say to children, “I’m not sure – what do you think?” with genuine uncertainty and curiosity, as we start to probe a poem for potential hidden meanings or themes. In this way, we can become used to asking the children questions that we, the teachers, do not know the answers to.

Layered reading of poetry – a Y3 example

The Sound Collector © Roger McGough

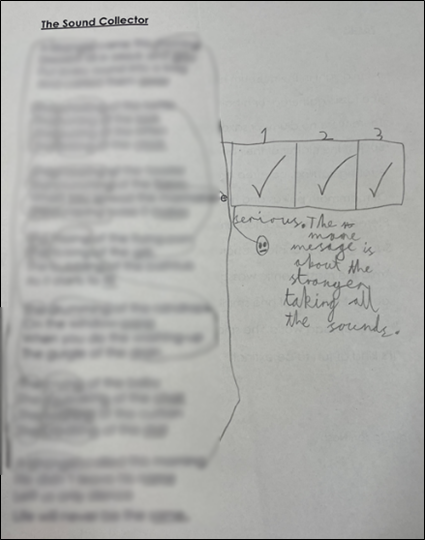

Here is an example of a child’s annotations of the poem ‘The Sound Collector’ by Roger McGough. You can watch Roger reading his poem online. The three boxes that the child has drawn (and ticked) on the page are used as a reminder that they needed to actively re-read the poem (not just skim or listen to it) and tick the box for each reading.

| Repeated readings | Key questions/ prompts | Explanation of activity |

1st reading (teacher reads aloud) | Discuss what you think is the mood of this poem… | In this example, the teacher initially provided the children with a range of emojis to select from. The class discussed which feeling/ mood the emojis could be representing and spoke about them within a specific context (e.g. “I remember a time when I felt ___ because___. The poem reminds me of that feeling because ______ “) to help decide what the mood of the poem feels like to them and why. |

2nd reading (teacher/ children read aloud in pairs or groups) | Discuss what you think is the main message of this poem… | Before the children were accustomed to doing layered readings of poetry, the teacher would give the class some suggestions of messages for them to discuss and choose from after their second reading. After a while, most children did not need this anymore and were confident to discuss and decide on what they thought the message of a poem might be, without prompting. Many children will take a text very literally – here is an opportunity to delve into wider interpretations and develop inferential skills (but again, being curious about all children’s interpretations and not looking for one ‘correct’ answer). You can see from the example, that this child took quite a literal explanation of the message of the poem but another child in the class thought that the main message was about ‘getting some bad news and then everything felt really weird, like the sound had gone’. |

3rd reading (children read individually or in pairs) | Find a word/ phrase/ verse/ section that interests you the most…. or Find a poetic device that the poet uses… | Upon the third reading, we can start to ask the children to give more of a personal response to the poem with some justification from the text or to start to think about, for example, the structure or poetic devices of the poem. In this example, the children discussed a poetic device that they could spot and this child underlined the use of rhyme and how that helped with the rhythm and emphasis of the words when he was reading it aloud. For support with teaching about poetic devices, Joseph Coelho’s MORERAPS poem is an incredibly helpful tool. |

4th reading (children read individually or in pairs) | Can you find any secret strings? | As Michael Rosen explains, this is one word or phrase that links to any other. This can be any pattern, such as a repeating image or anything that connects to something else. In this example, the child found secret strings between words that represented water as well as words or lines that repeated themselves. The imagery of water led to some wonderful discussions amongst the class, led by the teacher, concerning how our hearing is muffled or dulled underwater and whether the poet intended to create this feeling or not. |

The power of repeated reading here is in the magic that lies in the idea that we adjust our thinking about a text the more we read it. What often starts as a very literal reading of a poem becomes a deeper discussion, where children are genuinely curious to know and understand how their peers may come to different interpretations of the same text. This needs to be made explicit for children – we cannot read something in a vacuum; we bring to our reading the wealth of our own knowledge and experience, which are unique to us as individual readers.

Choosing poetry:

As Charlotte Hacking states, “So how do you become a good teacher of poetry? You read it, you respond to it, you even have a go at writing it. But to want to do this, you have to find poetry that speaks to you, that excites you, that inspires you, and then you do the same for your children.” (‘The Power of a Rich Reading Classroom’, 2020, p.43) Children need to identify poetry as being accessible to them, interesting, fun and engaging and about the things that mean something to them. With that in mind, children in primary school need to encounter a range of diverse poets and poetry – and here are some suggestions of poets and/or texts that we have enjoyed, plus useful resources.

Recommended poets and poetry texts (by no means an exhaustive list!):

| A selection of contemporary poets…. | A (small) selection of text recommendations: | A selection of classic poets… |

| Michael Rosen Valerie Bloom Joseph Coelho Benjamin Zephaniah Kate Wakeling Matt Goodfellow Adisa Eloise Greenfield James Berry Coral Rumble Brian Patten Grace Nichols Rachel Rooney George the Poet Karl Nova Debra Bertulis Brian Moses Mandy Coe Allan Ahlberg James Carter Roger McGough Neal Zetter Joshua Seigal John Agard A.F. Harrold Carol Ann Duffy | ‘The Final Year’ by Matt Goodfellow; illustrated by Joe Todd Stanton (verse novel, suitable for UKS2) ‘Love that Dog’ by Sharon Creech (verse novel, suitable for KS2) ‘Stars with Flaming Tails’ by Valerie Bloom ‘Rhythm and Poetry’ ‘by Karl Nova ‘Fairy Tales Gone Bad’ series by Joseph Coelho ‘Poems to Perform’ edited by Julia Donaldson ‘A Kid in My Class’ by Rachel Rooney; illustrated by Chris Riddell | Langston Hughes Christina Rossetti William Shakespeare Chaucer Elizabeth Barrett Browning Ted Hughes William Blake Alfred Lord Tennyson Emily Dickinson Wilfred Owen Walter de la Mare Spike Milligan Edward Lear Siegfried Sassoon Robert Browning |

Recommended websites to explore poetry further:

Poetry for Primary Schools — Just Imagine (a brilliant range of suggested poetry texts from EYFS – Year 6 from Nikki Gamble)

Poetry | Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (clpe.org.uk)

National Poetry Day - the UK’s biggest mass-participation celebration of poetry

Children's Poetry Archive - Listen to the world's best children's poetry read out loud.

References:

‘Poetry in Primary Schools’ 2023 Report: Poetry in Primary Schools 2023 | Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (clpe.org.uk)

‘What is Poetry? The Essential Guide to Reading & Writing Poems’ by Michael Rosen (2016: Walker Books)

‘The Power of a Rich Reading Classroom’ by the CLPE (2020: Corwin)

‘Reading Reconsidered: A Practical Guide to Rigorous Literacy Instruction’ by Doug Lemov, Colleen Driggs & Erica Woolway (2016: Jossey-Bass)