It was a pleasure to meet with Prof. Teresa Cremin again at HFL’s recent September Symposium. Although she is especially well-known for her groundbreaking and tireless research into the huge benefits of reading for pleasure, it has primarily been her work on writing teaching that has impacted me most personally, and profoundly changed my professional life, ever since I first met her 15 years ago. Since that time, children choosing to write in this country has fallen to rock-bottom. The latest National Literacy Trust report has found that fewer than 3 in 10 children and young people enjoy writing in their free time. The percentage of children who write something in their free time on a daily basis has halved over the past 12 months to just 1 in 9 in 2024. We need to ask ourselves why this is the case, and in doing so, turn our attention to what we, as educators, can control: the experiences of writing that children receive in the classroom. I thought it might be a good idea to repurpose this blog (originally shared on the WfP Centre website in 2021) and share it anew, in the hope that it might inspire some thought and encouragement to consider how we can put the enjoyment for writing at the forefront of the agenda in all of our schools - because, as I always say, writing is never just about writing.

First and foremost, if a child doesn’t want to write and/or feels that they aren’t very good at it – that’s often one of the biggest hurdles to their development as a writer. As teachers, it’s our job to listen – and I mean really listen – to our children and, before we do anything else, find out how they feel about writing and about themselves as writers. And in doing so, we need to ask ourselves the same question.

Teachers as writers; children as writers

Between 2009-2010, I had the privilege of working with Teresa Cremin, who was working with a group of teachers in Newham as part of a UKLA ‘Teachers as Writers’ project1. During our first session, she asked us to create ‘writing rivers’ – thinking about our range of experiences of writing from the earliest point in our lives up to adulthood. In doing so, we were challenged to consider how we felt about that writing and why. I quickly realised that, in contrast to my childhood, I no longer wrote for enjoyment or pleasure. I wrote for purely functional purposes – to send an email or create lists of tasks. No feedback, no creativity, no joy. What message about writing was I giving to my pupils? Well, here I came to the embarrassing realisation that I too was sucking the joy from their writing lives. When I met Teresa, I was teaching in year 5 and in my second year of teaching. At the time, my school used a literacy scheme which followed a formulaic pattern of looking at an extract or passage of text, answering questions about it, teaching an element of grammar or punctuation (out of context) and then asking the children to write in the same genre with the same content or context, using the aforementioned grammar/ punctuation (and often in just a day or two). I was the gatekeeper who decided what they would write about, how and when2 – and there was never any choice or discussion about this. At this point I should probably add that I am an English Literature graduate, and I just accepted that this was the way the subject was taught at school. Not once had I really questioned it, but at the same time I knew that the children didn’t really enjoy their English lessons – and I didn’t enjoy teaching them.

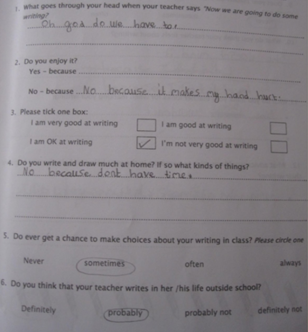

In fact, judging from their answers to a writing survey, over half (56%) of my pupils did not feel positively about writing at all. One child (I’ll give him the pseudonym Jason) was refreshingly honest in his responses.

I could feel his “Oh god - do we have to?” in the way he sat in his seat every day; the way he came into the classroom, looking at his feet and barely saying “Hello”. I could feel it from the way he scowled at other children whenever they asked him what book he was reading; the way he rolled his eyes when he was asked to pull in his chair. Jason was described to me on numerous occasions as ‘lazy’ and ‘rude’. Most teachers seemed to have dismissed him as a child who couldn’t be bothered, and by the time he arrived in year 5, Jason was falling far behind his peers. Highly unlikely to get the required level 4 by the time of SATs, his needs were no longer a priority, and he knew it. Looking back at his handwriting, it seems to say that he was trapped by a lack of fluency – unable to join his letters and write freely; he was stuck. He would often spend ages writing the date or a learning objective and barely get around to writing anything else before the lesson ended. His “Oh god - do we have to?” reflected exactly how Jason felt every single day. I admired his honesty hugely, and Jason’s admission has stayed with me ever since. In the fifteen years since then, all too often in the children I have met and taught, these struggles with writing go hand-in-hand with similar struggles in communication, behaviour, self-expression and self-esteem. It makes sense really – if you think you can’t write, does that mean you’ve got nothing to say? And if you’ve got nothing to say, what worth do you have?

Becoming a writer-teacher

After analysing the children’s feedback from their writing surveys, I decided to implement Teresa’s suggestions with gusto – clearly something had to change and it was going to start with me. We had talked about teachers writing alongside the children, writing the same thing we had asked the children to write. At first, I’ll admit I felt very sceptical – and anxious – about this concept. Surely the children would all be talking and not know what to do if I sat down and wrote alongside them? Surely they’d need me to help them when they were writing? I couldn’t believe what actually happened when I announced that, from now on, I would go on the same writing journey as them. At the time, we were writing our own narratives based on a hazardous journey, such as that of Michael from ‘Kensuke’s Kingdom’. I was also going to write an opening to my story. A silent respect followed an initially surprised reaction – they were far more quiet than usual and stayed that way for the rest of the lesson. They occasionally looked up to watch me as I chewed my pen, referred to the thesaurus, asked a child next to me to read a sentence to check it made sense to them. To my surprise, I found out that as long as they knew what resources they had at their disposal, they were quieter, more focused than usual and produced some wonderful writing. As well as doing my own writing, I would spend longer talking to the children, having in-depth conversations with children about how it felt to write, the process of writing and giving advice using tips and tricks that I had been relying on in my own writing process. We talked about how their writing made me feel as I read it, and whether that was their intention or not. I suddenly understood how it felt to feel that same frustration and vulnerability when staring at an empty page and the words don’t come. I would share that vulnerability by talking aloud as I wrote in front of the class – circling words that ‘didn’t feel right’ or underlining parts that felt boring or needed reworking. That day started a process that I have tried to stick to ever since. In my classroom, we all write – we are a community of writers, all working towards a common goal of publishing something we are proud of.

Putting pupil agency and autonomy on the writing menu

The next step was to focus on the children’s writing process. The time it was taking for Jason to meticulously write the date and LO before getting down to any writing was bothering me. What was the purpose of that anyway? Teresa wanted us to introduce writing ‘journals’ to the children. They could write whatever they wanted to in their journals; it wouldn’t be marked and they could share their writing only if they wanted to. Again, this felt like a risk. There were no rules about the journals, other than if you chose to draw or doodle you had to write about it in some way. I wondered to myself: what if a child didn’t choose to write at all? What if they had nothing to write about?3 As it turned out, as long as I kept the profile of the journals in the highest esteem, and they were given time to generate their ideas and we used them every day, this was never a problem. The excitement about the notion that they didn’t have to write the date, or cross out with a ruler, and they could draw on the front cover and doodle in the margins – in fact wherever they liked – was incredible. Never before had the children been provided with autonomy over their work in this way, or been provided with this level of trust. I also felt a little upset about their reaction – how sad that my pupils were so excited about a doodle and not having to write a date. What had it come to when I kept being asked: “But are you sure, Miss? We don’t have to underline the LO?”; “Won’t I get in trouble if I draw?” and “Can I really use a pen now?” or “Can we really write about what we want?” with a mixture of disbelief, excitement and anxiety.

In case you need any reassurance about the drawing element – the children’s drawings were an essential part of their writing. They provided a counterpart to their ideas and a process with which to visualise what they wanted to say and inform their word choices4. We would talk about their drawings and use them to consider impact on audience, the pictures we wanted our reader to see when they read our words. Jason took to his journal like a duck to water. He loved it - so much so, that when it came to ‘sharing time’5 he started to jump at the opportunity to share what he had written. I began to see a change in him on the day when he wanted us to read part of a setting description he was writing for a story based on a desert island (our reading of ‘Kensuke’s Kingdom’ was filtering into his own writing decisions). As he read his work, we all stopped at a phrase he had written and were unanimous in our praise. I still remember it now:

As I stepped into the soft, settling sand…

“Wow”, I said, “Jason – you’re a writer.” His reaction will never leave me. I don’t think I’d seen him smile like that before. Days after that, we could see the other children borrowing his phrase and it cropped up in some of their poetry after discussing alliteration – all referring to ‘Jason’s trick’. Jason began to start offering advice to other children; he wanted another journal to take home with him. He started writing stories with his mum.

Changing attitudes

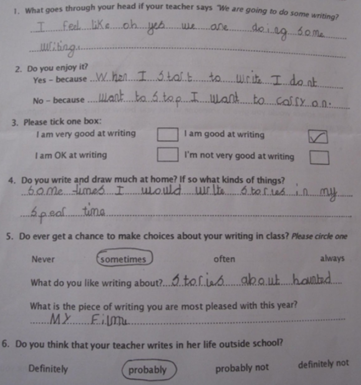

After the year (and the ‘teachers as writers’ project) had ended, I asked the children to complete the same survey. I was shocked by the change in their responses. You may remember that 56% of my pupils had felt negatively about writing. This had dropped to 12%, as now 88% of the children had a positive reaction to the thought of writing. Before we started the project, 74% of the class did not write, or rarely wrote, anything at home. This had reduced to 16%, as 84% were now continuing their writing at home or creating their own writing projects6. Jason’s responses were some that stood out the most:

I often wonder now about how Jason is getting on. Does he still write? Does he think he’s a good person? Is he happy? While I was delivering some training about writing for pleasure recently, I started talking about him and cried. He’ll never know what an impact he’s had on me; but his words will stay with me forever.

1 This project formed part of the UKLA ‘Ideas in Practice’ book, Teaching Writing Effectively: Reviewing Practice, published in 2011.

2 Harold and Connie Rosen wrote in The Language of Primary School Children (1973), p.92: “The question of children using written language for their own purposes and of maintaining confidence in their own ‘voices’ is one that presents itself not only in the introductory stages but all through primary school.” I had not thought about this before the ‘Teachers as Writers’ project.

3 I have heard this a lot – the assumption that children have no ideas and nothing to write about. I’m ashamed to admit I thought the same. I would now argue that if a child says they have nothing to write about, it’s because the idea that they have a choice in what to write is such an alien concept. By the time they’re in KS2, they truly believe they can only write something based on the content or context their teacher has provided for them. I can assure you – give a child the time to generate their own ideas and build back the trust that we, as adults and educators, value what they have to say and will listen to them, and they will have enough ideas to keep them writing into adulthood.

4 More information about children’s writing journals can be found in the UKLA Minibook (35) Children’s Writing Journals by Lynda Graham and Annette Johnson. As they state: “...the drawings children include in their journals are the visual counterpart to the written choices they are making. For children, illustration is a natural expression of their literacy, a means to communicate and transform their ideas and insights.” (2012) p. 16.

5 Sharing time is vital to the success of writing for pleasure (see Ross Young & Felicity Ferguson’s Real-World Writers pp. 71-72). It gives children the opportunity to see each other’s work and provide feedback, based on the intention of impact on reader (from the writer) and whether this has been successful or not. A visualiser is key here too – seeing the writing is as important as hearing it. Sometimes we can spend ages debating whether a particular verb has the right effect or not – this is where the magic happens.

6 According to Clark, C. and Teravainen, A. (2017) in Writing for Enjoyment and Its Link to Wider Writing, (London: National Literacy Trust) children who write at home are seven times more likely to write above the expected writing standard.

This blog was originally published in 2021, on the Writing for Pleasure Centre website. It has been revised and updated in September 2024.