This is not the fault of the teams. In fact, it is often the opposite: capable, dedicated in‑house staff doing everything they can within the limits of capacity and time. But the environment around them has changed faster than any one‑ or two‑person team can realistically keep pace with.

1. The single point of failure problem

For many trusts, the biggest operational risk sits in plain sight: staffing levels that create unavoidable single points of failure.

A technician responsible for multiple primary schools may provide excellent support—right up until the day they are on leave, unwell, or pulled into an urgent issue elsewhere. Unlike other functions, IT incidents often can’t wait. A failed server, a wireless outage, a compromised account—any of these can halt learning, disrupt safeguarding processes or take key systems offline.

When teams are this lean, even minor absences can reduce reactive capacity to zero. Central teams are then forced to shuffle priorities, often abandoning longer-term digital improvements to address immediate firefighting. Over time, this creates an organisational pattern where important but invisible work—patching, monitoring, testing backups, reviewing logs—simply cannot happen.

This is where the risk lies: not in the tasks you see, but in the ones that aren’t being done because there is no time or additional capacity to do them.

2. The automation gap

Modern IT environments in private sector rely heavily on automation—particularly Remote Monitoring and Management (RMM) tools—to keep devices secure, patched and compliant. These platforms are widely used in other sectors, yet remain inaccessible or unaffordable for many trusts operating with small teams.

Without automation, core maintenance becomes a manual process:

- Patching hundreds of devices

- Checking system health

- Monitoring alerts

- Ensuring antivirus and firmware are current

- Tracking backup status

When these tasks depend on someone being physically available, the workload quickly exceeds the hours available. This leads to what many experts refer to as “security debt”—a silent but growing backlog of updates and maintenance that weakens resilience over time.

In an era of rising cyberattacks on schools, this is an exposure MAT leaders cannot ignore.

3. The skill-level treadmill

Technology now evolves monthly. Cloud platforms, cybersecurity standards, safeguarding requirements, data protection obligations—each demands a level of ongoing professional development that is increasingly difficult for small internal teams to maintain.

The expectation on an in-house technician today is vast:

- Deep understanding of Google Workspace or Microsoft 365 administration

- Networking and firewall configuration

- Cybersecurity and threat detection

- Device management at scale

- Backup and disaster recovery

- Support for curriculum technology

- Compliance and data protection

But small teams rarely have the time or headroom to step away from day‑to‑day tasks of reactively resolving IT issues for long enough to develop this breadth of expertise. The result is often role fatigue, burnout and the risk of high turnover—leaving trusts even more exposed.

The issue isn’t capability. It’s capacity.

4. A shifting risk profile for trust leaders

Understaffing IT is no longer just a technical issue—it is a governance and strategic risk.

Reports such as the Kreston UK Academies Benchmark Report highlight a continued move toward trust‑wide digital centralisation as MATs grow. But centralisation without investment in resilience, tooling and specialist support can unintentionally amplify risk rather than reduce it.

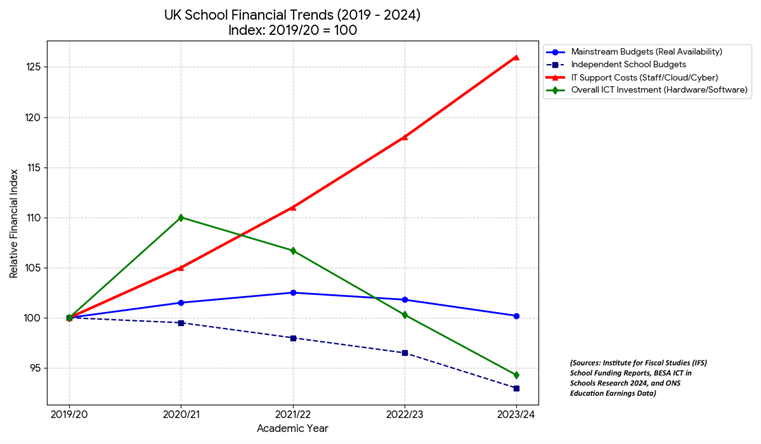

What was manageable five years ago is no longer sufficient today. The shift from on‑premise servers to cloud identity, the rise in cyber threats, and the need for automation mean that the traditional “one technician per 2-3 schools” model cannot keep pace with the complexity of modern digital estates.

Trust leaders increasingly recognise that resilience now requires:

- A team larger than one technician per 2 primary schools or two technicians per secondary school

- Access to wider pools of technical expertise

- Automation platforms that reduce manual workload

- Specialist escalation paths when complex issues arise

This doesn’t replace internal staff—far from it. It strengthens them.

5. Building a more resilient model by partnering with external MSPs to minimise cost while also reducing risks of failure

Many trusts are now adopting hybrid models that combine strong internal teams with access to external specialist support, additional capacity and enterprise‑grade tools. This approach helps address the challenges of:

- Cover for sickness and holiday

- Access to niche expertise that doesn’t justify a full-time post

- Reducing the manual burden on internal staff

- Improving strategic planning and governance oversight

- Ensuring resilience during growth or digital change programmes

For Trust executives, this is fundamentally a risk‑reduction strategy—one that aligns operational capability with the increasing demands of a modern digital education environment.

Support can be brokered through partnerships with IT Managed Service Providers (MSP) such as HfL’s own Technology in Schools. MSPs can bring bespoke wrap-around support and capacity through access to helpdesk facilities, cover for sickness and holidays, reduced cost of Automation, RMM and other tools and support for specialist projects and maintenance. Having an MSP on a retainer can add resilience to your trust and mitigate the ever growing risk that the skeleton crew is carrying.

Conclusion

Lean IT teams have served trusts well for many years. But the digital environment in which Trusts now operate has changed dramatically over the last 5 years. Complexity has increased, cyber risk has risen and many essential tasks now depend on expertise and tooling that a small in‑house team simply cannot sustain alone.

For CEOs and COOs, the question is no longer whether the current team is capable—they often are. The question is whether the environment around them has become too complex, too high‑risk and too fast‑moving for a small team, however talented, to manage in isolation.

Strengthening resilience is no longer about scale for its own sake.

It’s about protecting learning, safeguarding, data and operational continuity in a world where digital stability is now essential.

If you are interested to find out more or how HfL can help your Trust, reduce cost of licenses, provide holiday and sickness cover and elevate your internal IT Teams with expertise or RMM and Automation tools, please send us an email to itsales@hfleducation.org