So, in your school, is handover and transition treated like a relay race; seeing your staff as the team of runners, smoothly passing the baton to each other; allowing the next person to capitalise on the effective handover?

The analogy we often use for transition and handover in schools is of a relay race.

In a relay, a team works together. Each person runs their leg of the race. No one person can win the race alone. And the passing of the baton is key – a smoothly passed baton allows the next runner to make an effective start. They don’t lose time. With a dropped baton, time is spent fumbling to find it before the running can continue.

So, in your school, is handover and transition treated like a relay race; seeing your staff as the team of runners, smoothly passing the baton to each other; allowing the next person to capitalise on the effective handover?

The information we hold about the children we teach is vast and varied: medical needs (including who has asthma or allergies), children with SEND, what strategies have worked well to motivate the class and guide their learning and other sensitive information, such as which children might find it tricky leaving mum or dad in the playground. There is also lots of curriculum coverage and attainment information. We need to decide what would benefit the next teacher/s to know, to smooth the path of transition for the children.

In primary maths, information about coverage and learning could be key in ensuring that time is not wasted. There may still be some coverage gaps, after the disruption to learning in the last couple of years. It is important that the next teacher understands this to adjust the next years’ coverage accordingly; whether this is fitting in missed topics or giving time to secure learning that was covered but not fully secured. We know that if we start at the wrong pitch in learning, with a prior step missing, we often have to back-track later, which isn’t ideal.

When we begin teaching an area or topic, it would be normal to recap previous learning. But knowing whether we need to just remind and support children, or whether we need to properly teach or re-teach something is helpful to know.

What would it be helpful for teachers to share?

I’ll give you two fictional school scenarios:

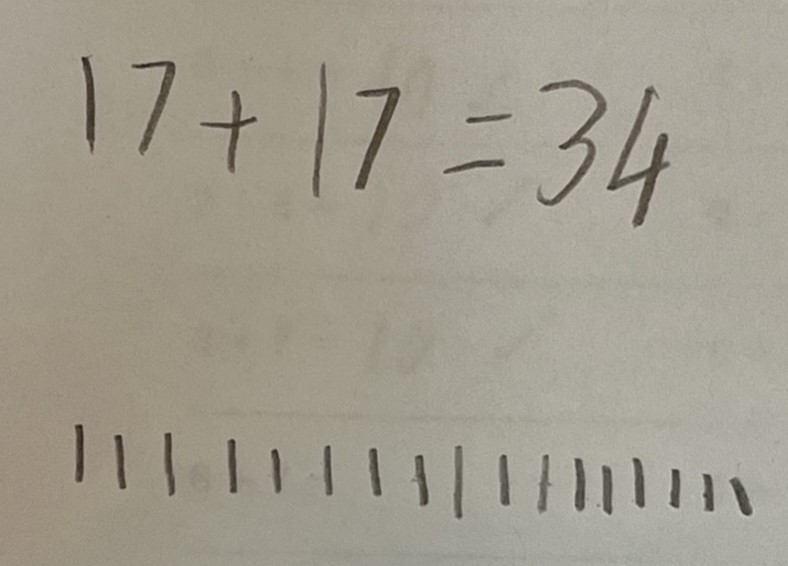

In Year 4, the children began work on counting through zero. They began to explore negative numbers. Some children did not fully secure the learning and so would count from 4 to -4 but miss out the zero.

In this first scenario, the learning is relatively small in the scheme of learning within Year 4 and could probably be fixed with a short focus on counting through zero before the Year 5 learning is layered on top. If you were teaching this class in Year 5, it would be helpful to know this but might not take much time to address it.

Here are the related National Curriculum programme of study statements:

- Year 4 - count backwards through zero to include negative numbers

- Year 5 - interpret negative numbers in context, count forwards and backwards with positive and negative whole numbers, including through zero

In the same Year 4 class, the children also took quite some time to learn their multiplication tables. As a result, they were not quite secure on using written multiplication by the end of the year. They could double numbers by partitioning / regrouping but not many children had secured a written strategy for multiplying any 2- or 3-digit number by a 1-digit number. They are now more secure with recalling multiplication facts, however.

In this second scenario, the learning of a written multiplication method takes time and rehearsal. Written multiplication is not often a ‘quick’ thing to teach. It is positive that the children’s multiplication fact recall is more secure, as this will help, but time still needs to be given within Year 5 to secure this learning before moving onto the Year 5 teaching.

Here are the related National Curriculum programme of study statements:

- Year 4 – multiply two-digit and three-digit numbers by a one-digit number using formal written layout

- Year 5 - multiply numbers up to 4 digits by a one- or two-digit number using a formal written method, including long multiplication for two-digit numbers

From the two scenarios above, the negative numbers issue is probably a smaller and easier gap to address. A short amount of time spent on recall and rehearsal of counting forwards and backwards through zero should be sufficient for the pupils to be ready for the Year 5 learning.

The written multiplication gap may take more work to close. Children will need to secure the method for multiplying a 2- or 3-digit number by a 1-digit number before attempting 4-digit numbers or multiplying by a 2-digit number. The overall maths plan may need to be adjusted to allow for additional time to secure this learning. Simply starting at the Year 5 pitch is unlikely to be helpful to many children and could even create bigger gaps in understanding.

The key is the Year 5 teacher having all this information so that they can plan accordingly before the point of teaching.

Back to our relay race analogy. Let’s explore ways that school leaders and maths subject leaders can enable effective handover to happen – passing the baton smoothly. Here are some ideas.

What might a maths leader do to support transition and handover?

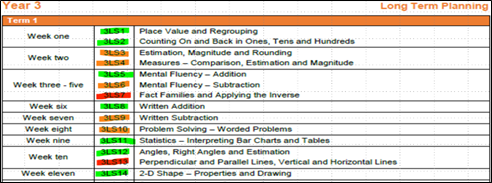

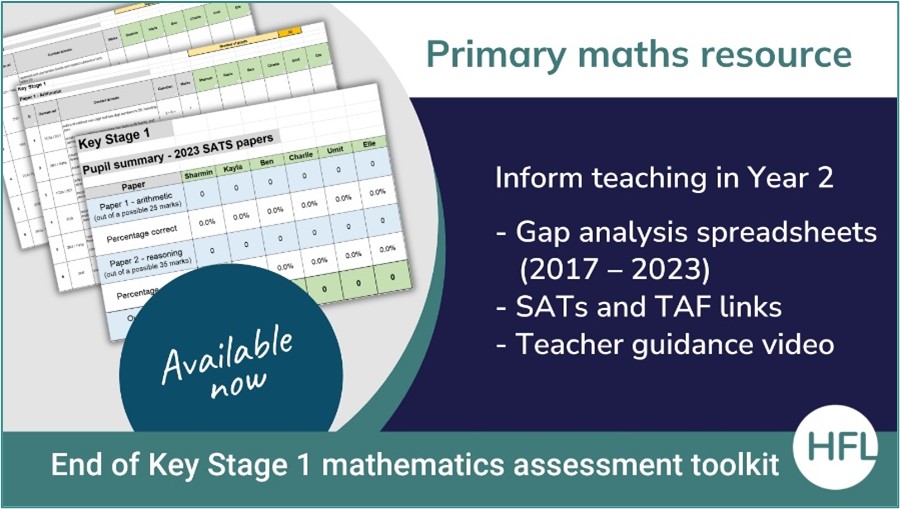

- ask current teachers to RAG rate their curriculum map or long-term plan to show the level of security and confidence with the learning for most children

- ask teachers to specifically identify anything that was either not covered or didn’t go as well and so will need time given to it before new learning is layered on top

- ask teachers to share specific pupil information including about attainment and progress, in whatever form your school uses

- remind the next class teacher to adjust their medium and/or long-term plan for maths, considering the handover information they receive

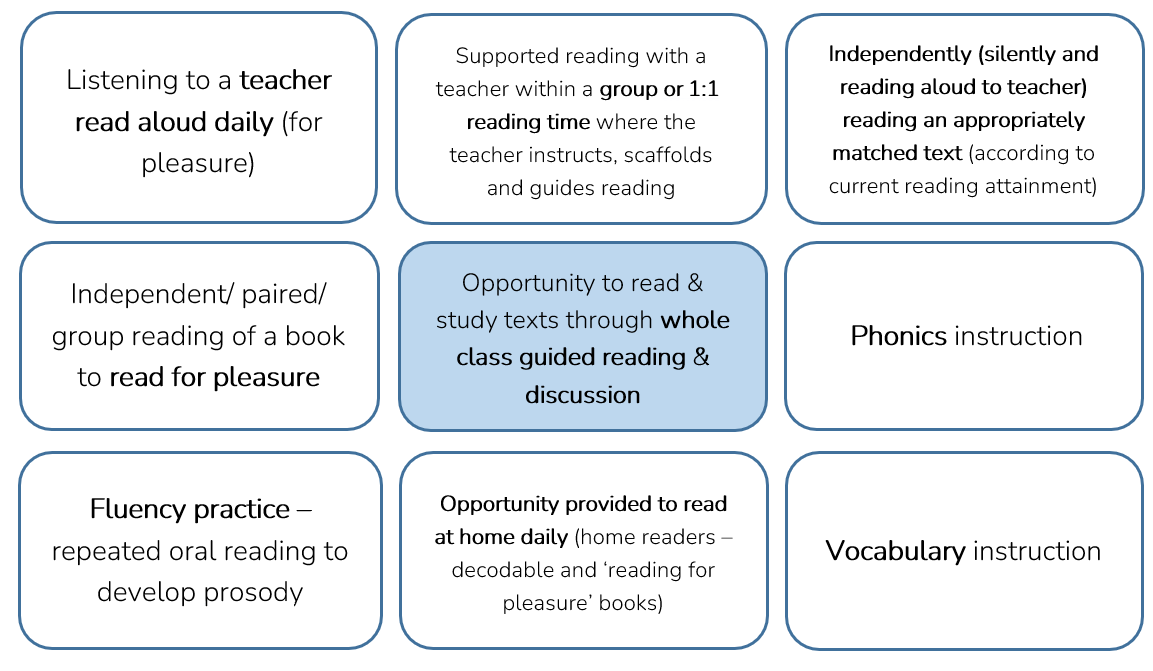

The idea of using red, amber, and green to indicate coverage and security of learning is not new. Many schools do this towards the end of the academic year and use it to support handover and transition.

Here you can see a part of the Year 3 curriculum has been RAG rated. Place value has been identified as secure (green) for most pupils. Two areas have been highlighted red and need a further conversation, to allow the next teacher to understand why and what they might do to address the gaps. It also looks like both mental and written subtraction are not secure for some children.

The above is one big piece of the jigsaw at this time of year. We need to ensure that we handover the information we have to ensure that the learning continues smoothly.

But, as well as the handover conversations between teachers, and what the next teacher does with this information, there are other ways to smooth the transition for children and their maths learning. Here are three further ideas, focusing on reducing ‘lost learning’ over the summer and allowing children to pick up again smoothly from where they left off in the previous year group:

- Keep fluency sessions going until the end of term and then pick them up quickly again in September

- Offer ideas to parents and families for everyday maths, which include fun things they might like to try at home, including over the summer break

- Plan in reactivation of key learning in September

We’ve explored each of these further below:

Keep fluency sessions going until the end of term and then pick them up quickly again in September

We know the end of the summer term can become very busy with sports day, trips, plays and celebrations. Time for the maths curriculum can get squeezed. This is a challenge but if regular maths input is reduced, the period the children are not ‘doing’ maths is extended and we know the summer holidays are long. Therefore, even if a daily maths lesson becomes impossible, continuing to do a 10 – 15-minute maths fluency session regularly will help to keep the learning ticking over.

Fluency sessions need to be short and sharp, picking four or five concepts to do daily. Doing each concept for a couple of minutes and repeating these, making very small changes, will help to embed and secure learning.

What concepts might you choose?

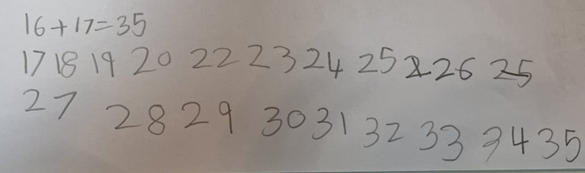

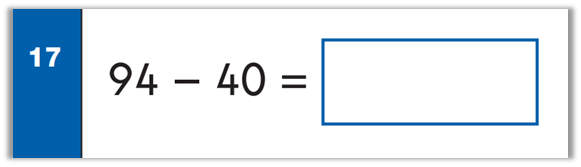

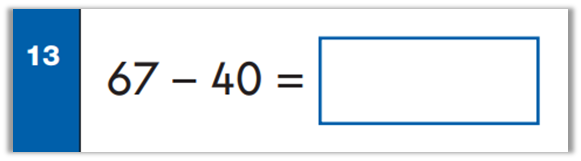

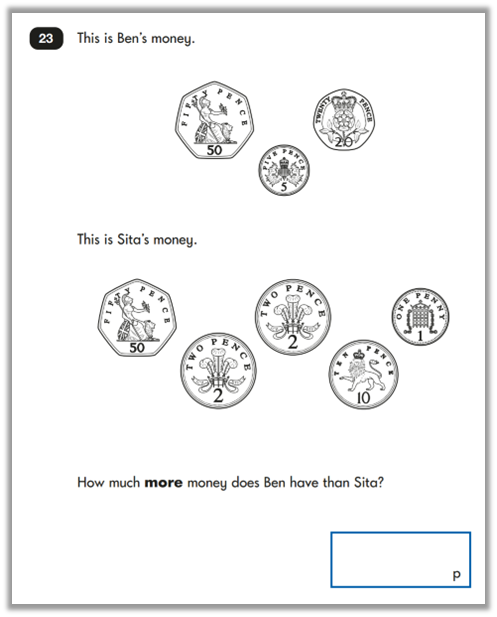

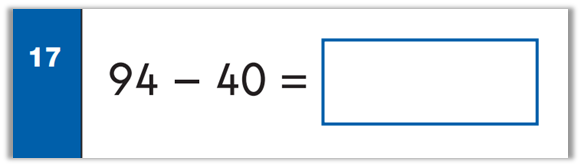

Choose high value learning that ensures that they are ready for their next stage in education. Most curriculum plans start with number and place value in September, so include counting, place value and number magnitude. Having base facts at your fingertips is essential so practise those. Reasoning about what strategies to use to solve a calculation is also important. Despite what most people think, maths is not all about the correct answer. It is also about how the correct answer is achieved. In schools currently, I am seeing lots of examples of highly inefficient strategies being used, particularly in KS1 SATs papers, but the correct is answer eventually found.

What might a fluency session look like?

Let’s consider a Y4 class.

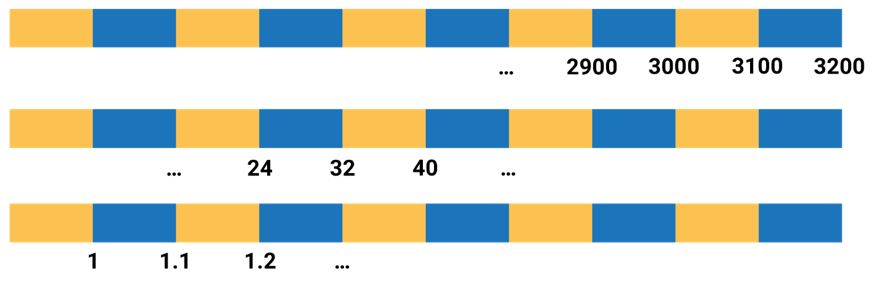

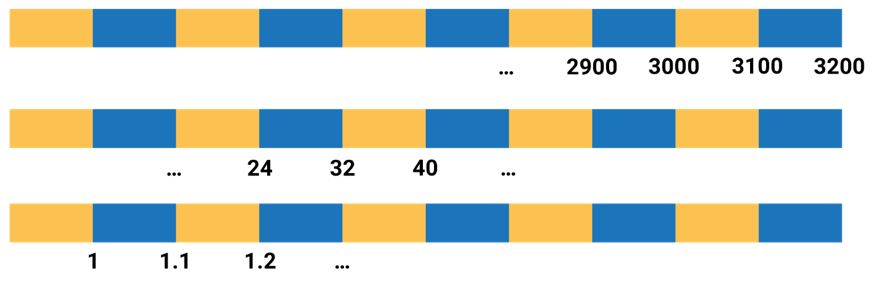

Concept 1: Counting

You could reach for a trusty counting stick or have a slide ready and rehearse counting in different intervals – bigger intervals, skip counting, decimal steps. Think about what the class need to practise to further strengthen their understanding of the number system or multiplication tables. Ensure you don’t always start at the start with zero; vary the starting point and count both forward and backwards.

Some examples:

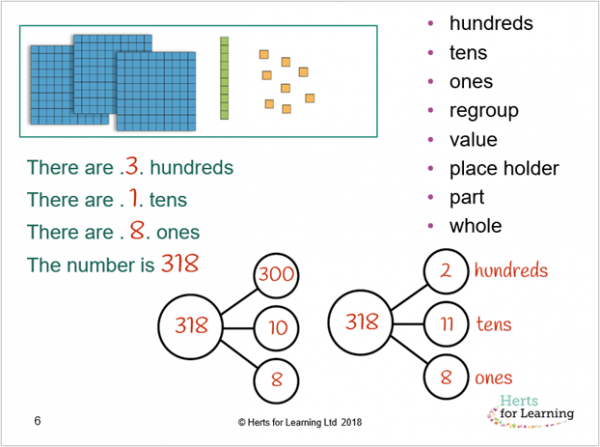

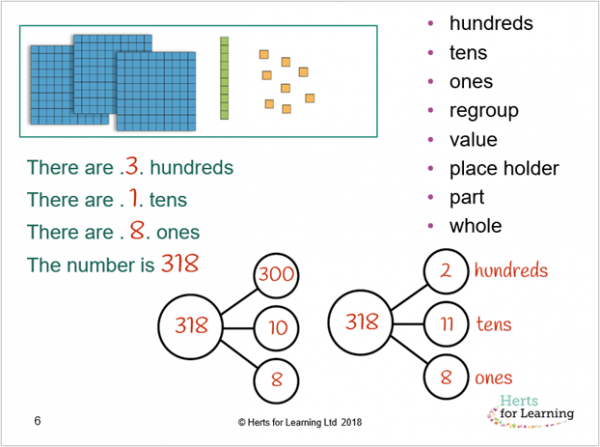

Concept 2: Place value

As with the counting, the number range could vary so it includes the fluency range for Year 4 – four-digit numbers and decimals to two decimal places.

The focus is on constructing and deconstructing numbers so there is a good understanding about how numbers can be manipulated.

Emphasise the flexible regrouping of numbers as demonstrated here; 318 is 3 hundreds, 1 ten and eight ones but it can also be 2 hundreds, 11 tens and 8 ones.

This understanding is essential to fully understanding formal written strategies. For more about the links between place value understanding and understanding written methods, read Can’t calculate? Could place value be the culprit?

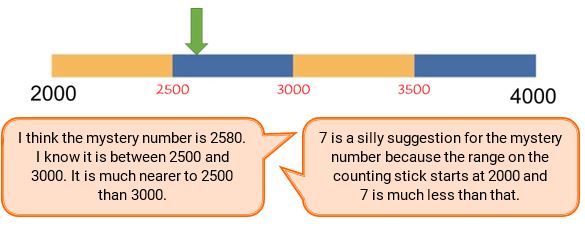

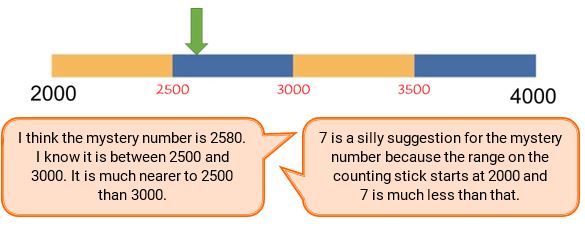

Concept 3: Magnitude of number

Children can find estimating along empty number lines or scales tricky. The first thing to secure is the usefulness of benchmarks. When introducing a new number range, always identify the midpoint (middle) first, and then the quartiles. Once these are known, ask the children to identify a mystery number. They will need the benchmarks to be able reason about their chosen numbers.

In addition, when discussing mystery numbers, as well as asking for sensible suggestions, also ask for silly suggestions – getting the children to give non-examples with reasoning is equally as beneficial – and everyone loves a silly answer.

Concept 4: Base facts

When rehearsing base facts, don’t be scared to go back to the basics. Revisiting bonds to and within ten is a good starting point and they can be quickly built back up to the age-appropriate fluency range.

3 + 7 = 10, so 0.3 + 0.7 = 1.0, and 3,000 + 7,000 = 10,000.

It is important that children see the link between the base facts and how these are used in the broader number range.

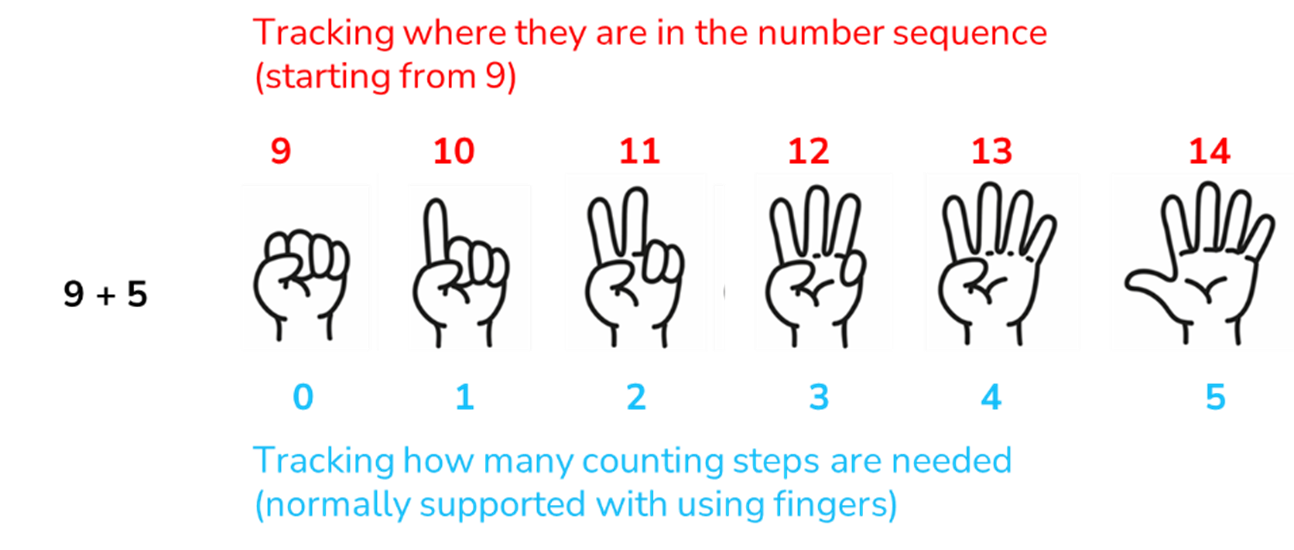

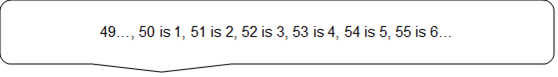

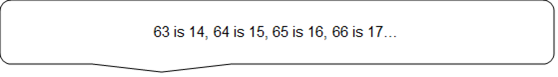

A quick and resource-free way to rehearse addition facts is to play ‘tennis’. You pick a target number, for example 14. You serve an imaginary ‘ball’ to your class saying a number, for example 9. They then return the imaginary ‘ball’ back to you saying the number that added to your number makes to target number so in this case the class would say 5. You then return the ‘ball’ saying another number, for example 3 and the class would return the ball saying 11 and so on.

The next time, you could play ‘tennis’ again with a linked target number such as 140, 1400 or 1.4. Make explicit links back to the base facts rehearsed earlier to ensure connections are made.

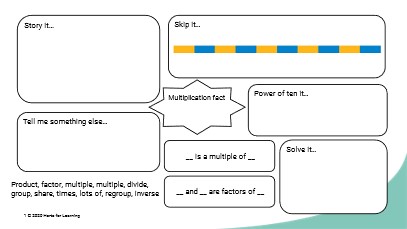

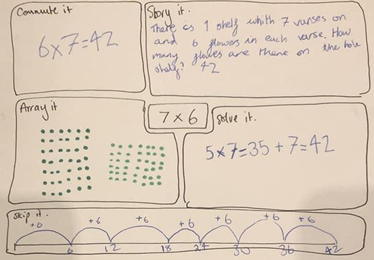

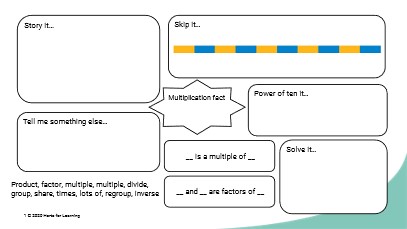

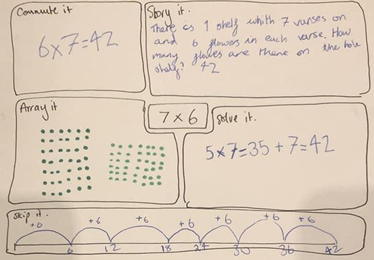

If you want to rehearse and explore multiplication facts, using this or a similar practice scaffold can support pupils making links. The idea with these is that you complete one part of the scaffold, and the children complete the rest.

I might give the multiplication fact in the middle as 7 x 6 = __ and ask pupils to complete the other sections. This version includes key vocabulary and a ‘tell me something else…’ box. This is useful because you can encourage children to be creative and show off their knowledge.

Here is a similar scaffold:

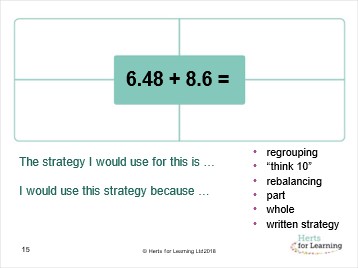

Concept 5: Strategy choice

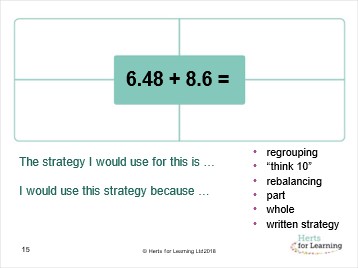

When faced with a calculation, it is important not only to calculate it correctly but also consider the most appropriate strategy, giving time to discuss the most efficient way to solve a calculation.

Let’s take an example from the 2022 KS2 SATs, maths arithmetic paper (Q 6):

6.48 + 8.6 = ___

It is within the Year 4 fluency range so could be part of the Year 4 fluency session.

This simple structure encourages children to think about multiple ways to solve the same calculation and consider the most accurate and efficient strategy for them. The idea is that you put the calculation in the centre and think of up to four different ways to solve it.

What four strategies would you choose? Which one do you think is the most efficient and accurate for you?

Read more about fluency sessions.

What ideas could be shared with parents and families for everyday maths, including fun things they might like to try at home over the summer break?

As we have already mentioned, the summer holiday is long and during this time, children will not have maths lessons, and we wouldn’t want them to! However, we might want them to continue to have opportunities to think mathematically.

Planning a day trip, or holiday outing

There are many decisions to make when planning an outing. As a parent myself, I wouldn’t want my children planning every trip, but even if the adult decides the destination, there are still lots of other aspects to discuss, agree and plan:

- time – What time do we want to arrive? What time will we need to leave home to arrive at x time? How long will we be there?

- money – Cost of tickets, amount for lunch, snacks or treats, or saving pocket money for the the gift shop?

- measures – How far away is it? What is the best route?

- spatial thinking – following a map

Playing a board game

Most board games support mathematical learning. Track games are particularly great at supporting counting, but many also support problem solving. Even in simple games such as Ludo or dominoes, there is an element of strategy – deciding when to start the next counter, considering the position of other people’s counters, considering the matching dominoes in your hand that link together, for example.

In games such as Monopoly, Cluedo and Ticket to Ride, many problems need solving and working strategically or systematically are important skills that can be developed, as well as guessing and checking, or visualising. All play can have mathematical connotations.

Finding ‘Maths Everywhere’

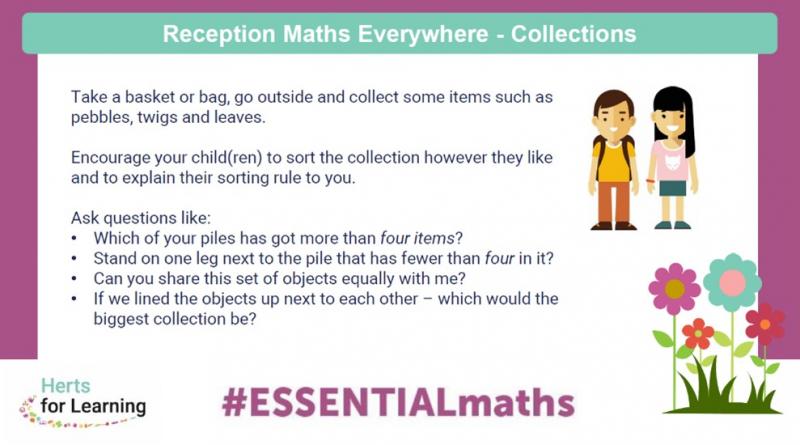

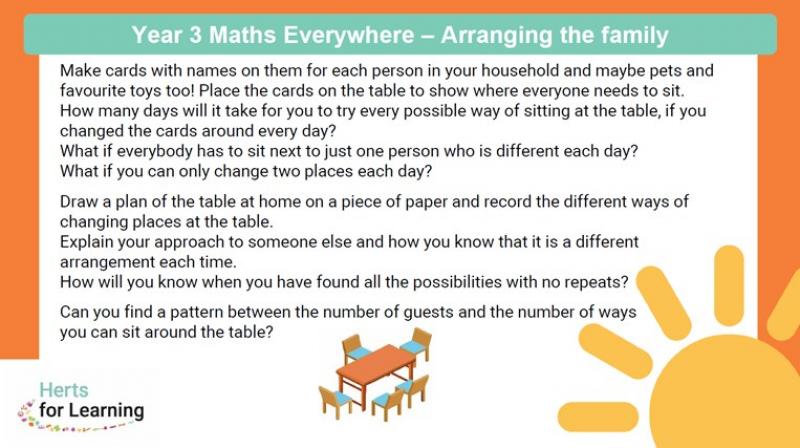

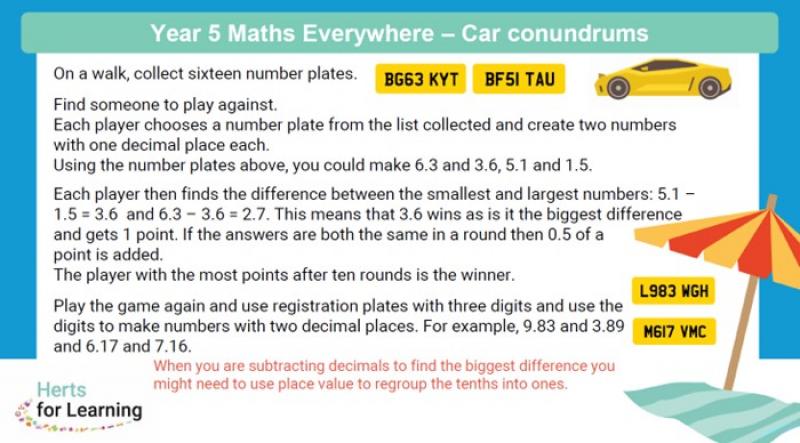

Doing tasks such as setting the table or putting toys away in the correct place have mathematical value. Our Herts for Learning ‘Maths Everywhere’ resources are perfect for giving ideas. They range from Reception to Year 6 in focus, but all could be adapted to make them appropriate to different ages of children within the same family or group.

The ‘Maths Everywhere’ cards make simple suggestions. Above are just 3 of the set. The first is about collecting, sorting, and counting objects. For younger children this is particularly helpful as they involve skills such as matching, subitising and classifying.