(Updated Autumn 2024, to link to Sept 2024 version of Ofsted EIF and Handbook)

This blog summarises some of the key points I made in my recent talk given at the Herts for Learning Curriculum Symposium, which focused on the role of assessment across the curriculum, with particular reference to the new Education Inspection Framework (EIF) and School Inspection Handbook. Not that I think we should ever do things just because we think they are what Ofsted wants us to do: I truly believe and have always advocated that educationalists should act in the way that they believe to be right and in the best interests of the children. But, when that also happens to coincide with what Ofsted are saying, it’s a win-win. And this new Education Inspection Framework represents some real shifts (for the better) in Ofsted’s approach to assessment.

There are a number of key paragraphs in the School Inspection Handbook that relate to assessment practice. I shall explore a few that I think are particularly significant.

Firstly, regarding the implementation of the curriculum, paragraph 243 indicates a number of key areas on which inspectors will focus. The two bullet points that specifically refer to assessment state that inspectors will focus on the extent to which teachers:

"... check pupils' understanding systematically, and identify misunderstandings and adapt teaching as necessary to correct these

use assessment to check pupils’ understanding to inform teaching"

(School Inspection Handbook, paragraph 243)

In relation to the school’s use of assessment, the Handbook states:

"When used effectively, assessment helps pupils to embed knowledge and use it fluently, and assists teachers in producing clear next steps for pupils."

School Inspection Handbook, paragraph 387)

NB this paragraph then goes on to warn that:

"However, assessment is too often carried out in a way that creates unnecessary burdens for staff and pupils. It is therefore important that leaders and teachers understand its limitations and avoid misuse and overuse."

Looking at these points, we can see a clear emphasis on what is going on in the classroom - i.e. in the moment, informal assessment. So we need to ask ourselves the questions, how well are teachers using formative assessment techniques to:

- find out what children already know so that they can build on this?

- unpick children’s misconceptions?

- check learning within (as well as at the end of) lessons?

- provide effective feedback to move learning forwards?

In addition to these points about classroom assessment, the Handbook discusses (in the section 'Talking about the curriculum with leaders') how inspectors will want leaders to set out the scope of what they intend pupils to learn, including how the subject content has been mapped out across the year groups and the extent to which clear end points have been established. (Paragraph 259)

So we also need to ask the question, how do teachers (and subject leaders):

- evaluate whether children are where they should be in their learning journey through the school curriculum?

In answering that last question, though, we need to take note of the messages around data collection and analysis not creating excessive workload. It’s not that practices such as tracking pupil attainment over time need necessarily disappear altogether, but such practices must be proportionate and purposeful. More on this later in this blog. But for now let’s keep the focus on the formative.

The first four of the above questions are all about formative assessment, whilst the fifth is slightly different in that it focuses on evaluation in a more summative sense. (Evaluation can of course also be used formatively, e.g. if it leads to curriculum development, but often summative assessment is a means to an end). For me, that ratio of 4:1, formative to summative, is a good guide to how we should be investing our assessment energy: overwhelmingly focusing on the formative, as that is where the greatest benefits to learning will lie.

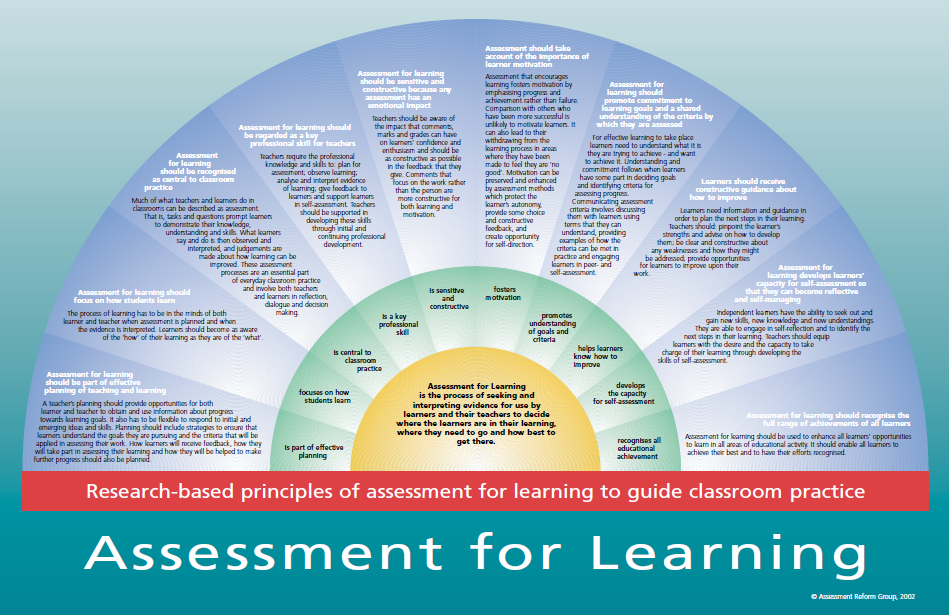

There is plenty of evidence that formative assessment, or ‘assessment for learning’ (AfL) if you prefer, can have powerful impact on learning, when its core principles are at the heart of teachers’ practice. Formative assessment is fundamental to becoming a ‘responsive teacher’ – one who skilfully uses questioning techniques to find out what every child in the class thinks, knows and understands, and what the misconceptions and gaps are – and then, crucially, responds to this information: addressing those misconceptions in the moment, adapting the lesson plan as necessary.

Here’s a reminder of the ten principles for formative assessment that were set out by the Assessment Reform Group in 2002.

The above image can be downloaded as a pdf.

But AfL can sometimes be misinterpreted when it comes to classroom practice or school policy, and can end up being distilled into a set of strategies or rules that might be somewhat divorced from the core principles. Our ‘Focus on Formative’ work with schools is aimed at supporting teachers to develop a meaningful understanding of the purpose of formative assessment strategies, so that they can embed these into their practice in a truly impactful way.

There are many strands to this. For now, though, I will just mention one area: feedback.

Effective feedback, whether it be written or verbal, should move the learning forwards. For me, the following quotation is still a fundamental guide to the purpose of feedback:

"Comments should identify what has been done well and what still needs improvement, and should give guidance on how to make that improvement…to be effective, feedback should cause thinking to take place."

Working inside the black box, Black et al (2002)

School marking/feedback policies may dictate that teachers use particular colours of highlighter pens, or give ‘three stars and a wish’, or refer to polishing pens or indeed state that the school has moved away from giving pupils written feedback altogether in favour of verbal comments or a conferencing approach.

However I would argue that all of those things are peripheral. The most important thing to consider is the impact of the feedback: to refer again to the above quotation, has that feedback caused thinking to take place?

Regardless of how the feedback is given, what matters is the content of the feedback and the timing (i.e. focused on the intended purpose of the learning, and the more immediate the better). And it’s important to note that feedback might need to look different for different learners. Let’s not worry ourselves about consistency in terms of what things look like. School policy can, and should, dictate consistency in terms of the principles to which all staff are expected to adhere, but should allow the flexibility for teachers to use their professional knowledge of the child and give the feedback that is going to be of greatest benefit to that individual at that point in time. Feedback to a novice learner may very well look quite different to that which is given to a learner with a more advanced understanding of a particular concept. For some learners, a coaching approach might be hugely beneficial, although a learner already needs to have a pretty good grasp of where they are in their learning and where they want to get to for a coaching approach to be effective. This blog, written by my colleague Sophie MacNeill, provides further thoughts on effective feedback.

To return to my earlier questions, effective techniques to gauge children’s understanding of subject content prior to teaching a unit of work, during the teaching and at the end are also very important. Knowledge organisers, concept cartoons, mind maps, true/false quizzes etc can all be useful tools to use as starting points for class discussion which can illuminate for the teacher the areas of the subject where the knowledge is already secure, areas where misconceptions lie, and areas where the knowledge is lacking. Such techniques are particularly useful when there is a spiral curriculum in place. For example, children will have learnt about the topic of ‘animals including humans’ during Key Stage 1, and will likely revisit this topic at various points in Key Stage 2. It will be important for teachers to ascertain what has been remembered from the previous teaching when planning the next unit. One cannot rely on a simple record of what was taught in the previous year as a guarantee that those concepts made it into the long-term memories of all the children. During the Curriculum Symposium, we heard from both Mary Myatt and Clare Sealy about the importance of understanding schemata - the conceptual frameworks we internally construct as we learn - and the importance of challenging misconceptions that may exist within these schemata. Good classroom assessment techniques play a vital role here.

During teaching, the idea of the ‘hinge-point question’, explained by Dylan Wiliam in brief video clips on Vimeo and YouTube, is a hugely powerful strategy to enable teachers to make evidence-based decisions about the direction of the lesson. This absolutely strikes a chord with that Ofsted bullet point I quoted earlier:

"Teachers use assessment to check pupils’ understanding in order to inform teaching"

Amongst the various competing demands on teachers’ time, I feel that time spent devising really good hinge-point questions to use in lessons is particularly worthwhile. As Dylan Wiliam explains, the trick to devising a good multiple choice hinge question is that it considers the possible misconceptions that different learners may have. The wrong answers should be those typically given when common misconceptions are held, and it should be extremely unlikely that someone would arrive at the right answer but for the wrong reason. For further professional development in the concept of the hinge question, a read of ‘Embedded Formative Assessment’ by Dylan Wiliam is recommended.

This blog cannot hope to cover an exhaustive range of formative assessment strategies, but what I hope I have achieved with these few examples is to illustrate the importance of teachers continually developing and upskilling their classroom techniques - not just because of Ofsted but fundamentally because it will improve teaching and learning across the school.

In terms of end-of-unit assessment - the means by which teachers seek to determine how well the students have learned the material - thought needs to be given to:

- the particular areas of knowledge, skills and concepts that we wish to assess

- the range of approaches that we might use as vehicles for the children to demonstrate their learning

- the extent to which the approach to assessment genuinely explores that knowledge has gone into children's long-term memory, not simply regurgitated on a surface level soon after the point of teaching

On the first of those points, this is where the curriculum mapping is essential. Across your school, is there a clear map in place that shows in which year groups you expect children to learn key concepts? Are there particular milestones, in terms of skill progression or areas of knowledge? Which key skills do you expect children in Year 4 to develop in art? What are the expectations of a Year 1 child in geography? These things will vary from school to school. Tim Oates encourages us to teach fewer things in greater depth, and each school will make different choices about what to prioritise in its curriculum. The curriculum choices you make will determine the key milestones on which your summative assessment should focus. They will probably also determine the choices you make about what data to collect.

In terms of the range of approaches, the only limit is your imagination. Whether you ask your children to produce a dramatic presentation, a cartoon, a poem, a website, a poster, a podcast, an assembly, a piece of writing or even a good old-fashioned test (or whether the children make their own choice from any of the above) - one thing we do need to ensure is that we are maintaining the integrity of the subject. Cross-curricular work can be wonderful, but we need to be clear about the focus of our assessment. If we ask our children to write, for example, a diary entry or letter from the perspective of a particular historical character, are we assessing it from a literacy perspective, or looking for accurate historical knowledge, or both?

Before I finish this blog, I would like to briefly return to the topic of summative assessment and the extent to which subject leaders in schools need data to be able to demonstrate the progress pupils are making across the school.

Paragraph 389 of the School Inspection Handbook indicates that inspectors will consider whether data collections are “proportionate, represent an efficient use of school resources, and are sustainable for staff”. Crucially, any data collection should serve a purpose - it should inform clear actions, for example indicating areas of the curriculum that require greater teaching focus, or professional development, or groups of pupils that need further support etc. I would encourage school leaders to think about their current data collection practice and carry out a quick cost/benefit analysis. Consider how much teacher time and energy goes into each data collection, and consider what benefits they bring. Do the benefits justify the costs?

Paragraph 388 states that "assessment should support the teaching of the curriculum, but not substantially increase teachers’ workloads". The 'Making Data Work' report recommends a maximum of three ‘data drops’ per year.

It is particularly important to note paragraph 250 of the Handbook at this point, which I quote in full below:

"Inspectors will not look at non-statutory internal progress and attainment data on inspections of schools. That does not mean that schools cannot use data if they consider it appropriate. Inspectors will, however, put more focus on the curriculum and less on schools’ generation, analysis and interpretation of data. Teachers have told us that they believe this will help us play our part in reducing unnecessary workload. Inspectors will be interested in the conclusions drawn and actions taken from any internal assessment information, but they will not examine or verify that information first hand. Inspectors will use published national performance data as a starting point on inspection, where it is available."

The significance of the above should not be underestimated. It opens the door for true data honesty. We no longer need to worry about external eyes looking at our internal data and basing judgements upon it, so the ongoing assessments that teachers are making can genuinely reflect how securely children are learning key concepts, without any pressure to, shall we say, over-optimistically massage the figures. In fact the opposite should be true - we need teachers to be brutally honest in their assessments, because the fundamental point of the assessment is to provide an accurate picture to school leaders which they can use as the basis for decisions. If boys’ standards in maths in Year 4 are slipping a bit, or girls’ progress in reading across the school is not as strong as one would hope, then leaders need to know about this so they can consider what actions may be required - resourcing, training, targeted support etc. To reiterate a key phrase from paragraph 250, ‘Inspectors will be interested in the conclusions drawn and actions taken from any internal assessment information, but they will not examine or verify that information first hand’.

Matthew Purves, formerly Ofsted’s Deputy Director for Schools, talks about the rationale for inspectors not looking at internal data in this short clip.

This blog has only scratched the surface. There is much more for us to consider in terms of how we refocus our thinking on assessment. Its place is to support and inform our teaching of the curriculum, not to drive it. Our curriculum should not be determined by what’s going to come up on a test. The curriculum must come first and should be the master. Assessment should be the servant.

References

Assessment Reform Group (2002) Assessment for Learning: 10 principles

Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall & Wiliam (2002) Working inside the Black Box: Assessment for Learning in the Classroom

Wiliam (2017) Embedded Formative Assessment