SENCOs – Start September strategically

September. Even more so than January, for those of us who work in education, the start of the autumn term is the fresh start, the time for plans and resolutions about how we want to work differently this year. The summer holidays have hopefully given some time and distance to the year that has passed, with a chance to reflect on our own professional WWWs and EBIs (‘what went wells’ and ‘even better ifs’). Now we’ve got past the initial busy first few days of term, it is a good time to reflect on plans for the coming year.

When we talk to SENCOs, their (academic) new year resolutions often include the ambition to be more strategic – to find a way to move beyond completing the never-ending paperwork and to increase their focus on leading inclusion across the whole school. We hear, ‘I want to get into classrooms more’ or ‘I want the chance to do more staff training.’

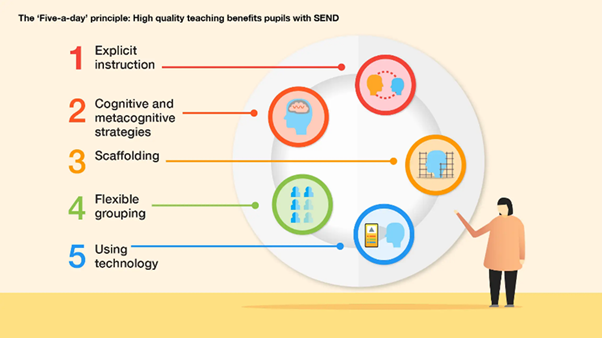

SENCOs understand the value of time spent advising, supporting, and training their colleagues and recognise that consistently high-quality teaching is one of the greatest levers to ensure good outcomes for learners with SEND.

Remember, the SENCO’s role comes with strategic responsibilities as well as managing the day to day:

The SENCO has an important role to play in determining the strategic development of SEN policy and provision in the school.

SEND code of practice (2014) 6.87

The recently published SEND and AP Improvement plan (March 2023) reinforces this expectation, describing the need for the SENCO role to be “whole-school, senior and strategic”

And yet, being strategic doesn’t happen automatically, and it can be hard to carve out time to focus on these high-impact activities. The reality is urgent tasks are visible, often important and every SENCO spends a significant part of every day reacting to demands on their time: a dysregulated child needs immediate support; a phone call interrupts your focus; staffing absence needs to be covered.

Most of us spend too much time on what is urgent, and not enough time on what is important.

Steven Covey

This is not something to feel guilty about…. it is something to be curious about and to reflect on. The good news is that most strategic tasks often don’t take that long once you have found time for them. The 80-20 rule is the widely regarded principle that if you focus on the right priorities you can get 80% of the total impact from just investing 20% of your time in the right place. (What is the 80-20 rule, and how to apply it in your life | Tony Robbins). How might this work for you? For example, a one-hour staff meeting training about the early identification of need may have a positive impact that eventually saves you time minimising the number of ad hoc conversations with teachers throughout the year. Or, taking some time to research and introduce the latest approaches to supporting self-regulation, will hopefully mean that, over time, there are fewer incidents of dysregulated behaviour that urgently need reacting to.

So, if your new year intention is to be more strategic this year, here are five top tips for how you can increase the likelihood of success.

The key is in not spending time, but in investing it.

Stephen R. Covey

1) Make a strategic plan:

The first task is to be clear what leadership and strategic activities you want to complete. To maximise the impact, these need to be relevant to the context of your school, so a good starting point is to review your self- evaluation framework (such as the Hertfordshire SEND Benchmark and Planning tool) and your school’s development plan for the current priorities. Be selective, not comprehensive. From your settings’ priorities, decide only three or four strategic activities for the year that will add the most value.

The ‘Big Rocks’ concept might be useful here; the origin is unknown, but this story was made popular by Stephen Covey in his book The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. Greg McKeown summarises it in his book, “Effortless”:

A teacher picks up a large empty jar. She pours in some pebbles at the bottom. Then she tries to place some larger rocks on top. The problem is that they don’t fit.

The teacher then gets a new container of the same size. This time she puts the large rocks in first. Then the small pebbles in second. This time they fit.

Greg McKeown, Effortless

In this metaphor, the big rocks represent the strategic monitoring and evaluation activities such as learning walks, training, policy review and development, pupil progress meetings, analysis of trends and patterns. The small pebbles are the operational tasks such as planned meetings and processes, referrals, administration. The sand is the day to day urgent and visible tasks that you need to react to.

Once you have chosen your ‘big rocks’ for the year, set SMART objectives for exactly how and when you are going to complete these and block out time for them in your diary. Research shows that scheduling when and where you will do something makes it much more likely that the task will get done. (How to Focus on What’s Important, Not Just What’s Urgent (hbr.org)).

2) Find an accountability friend: sharing your plans increases the commitment to them

By publicly announcing an activity, for example that you will ‘launch a parent questionnaire in May 2024’ to your senior leadership team, to your teaching staff, or even to parents in a newsletter, there is less chance that this action will be ‘bumped’ by urgent firefighting tasks.

Planning a joint activity with your SEN link governor is a great way to keep focus; whilst colleagues might interrupt you if working on your own to ask for help with an urgent issue, they are more likely to find another way if they can see you are in a scheduled meeting. To support you, we have provided templates for eleven strategic monitoring and evaluation activities you can complete alongside your SEN link governor in the Hertfordshire SEND toolkit.

3) Do not try and do too much

If this way of working is new to you, then be realistic about what you can achieve within the time you have available. One good quality strategic monitoring or evaluation activity per half term might be an initially achievable aim. If you didn’t manage to fit in any learning walks last year, then it’s highly unlikely that you are going to be able to complete one a fortnight this year. So be kind to yourself and don’t set yourself up to fail.

4) Share the strategic tasks for SEND between SLT and middle leaders:

As Gary Aubin puts it, in ‘The Lone SENDCO’:

If every teacher is a teacher of SEND, then every leader must be a leader of SEND…. Go back to your priorities. If supporting students’ vocabulary or boosting reading is a priority for you as SENDCO, this will be more impactful if middle leaders can champion this in their area also.

Gary Aubin, The Lone SENDCO.

Can subject leaders include subject specific adaptations for learners with SEND in their CPD sessions for staff? Do all leaders review learners with SEND in their monitoring activities? Can whoever reviews attendance in your school provide you with the analysis for learners with SEND? Can your SEN link governor complete a website check for you?

Whenever you can work ‘with’ someone, you will also be adding that very important value– capacity building in others by sharing your experience, knowledge, and skills of SEND.

5) Identify the unimportant and non-urgent tasks that you keep doing

Find ways to either streamline these processes so they take less time, delegate them to someone else or give yourself strict time limits to complete them as quickly as possible. Also be aware of others who take your time; it can sometimes feel that your non-class time is swallowed up by whatever is needed; covering playground duty, putting up a stage, photocopying assessments. So be assertive enough to say the polite, “yes, but…” such as “I can help with lunch duty today, but that means I won’t be able to complete the attendance analysis I had planned.” Once the requester is aware of the consequence of what they are asking you to do, often they will rethink and find a different option for solving their problem.

In modern life, it is easy to fall into the trap of being “too busy chasing cows to build a fence.” The sorts of scenarios you most want to avoid are fixing the same problems over and over or giving the same instructions repeatedly. To overcome a pattern of spending all day “chasing cows,” you can outsource, automate, batch small tasks, eliminate tasks, streamline your workflow, or create templates for recurring tasks. Look for situations in which you can make an investment of time once to set up a system that will save you time in the future.

Alice Boyes, How to Focus on What’s Important, Not Just What’s Urgent (hbr.org)

Hold tight to your ambition to be more strategic – to spend more time in classrooms and in improving outcomes for learners. You will need to be adaptable and resilient as challenges on your time throughout the year are inevitable, but your ability to respond, learn from failures, and regroup will steer you through.

And finally… don’t forget to acknowledge and celebrate the achievements and positive impact that result from your strategic leadership in the SENCO role. Good luck this year.