Mastery readiness – taking small steps to make a big difference

In strategic partnership with Matrix Maths Hub, the HFL Education maths team lead the Mastery Readiness stage of the National Centre for Excellence in the Teaching of Mathematics (NCETM) Teaching for Mastery Programme. Since 2015, almost a third of primary schools in England have been involved in this national programme.

A question that we are often asked is, ‘What is the difference between Mastery Readiness and the teaching for mastery programme?’

Our answer?

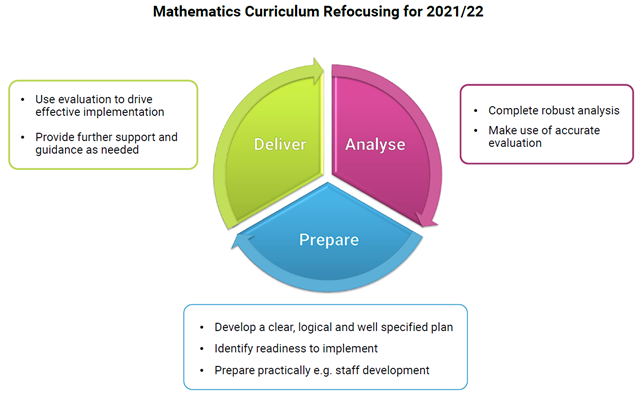

The Mastery Readiness year allows schools to slow down, take stock and then move into the developing year from a place of genuine understanding of their needs and priorities on the road to teaching using a mastery approach.

During the year, Mastery Readiness leads work with 1 or 2 teachers from each school (the project teams) as well as the Headteachers. The project team participate in half-termly workgroups and collaborate with teams from other schools as well as receiving half termly school visits.

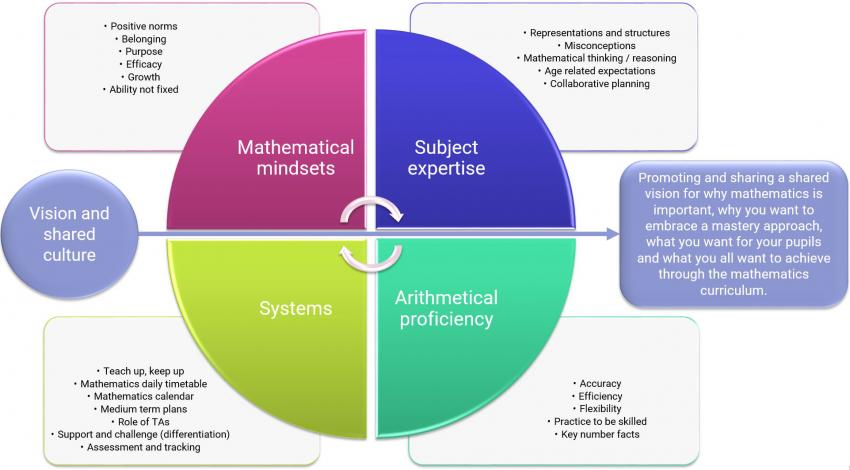

The school visits are personalised to the needs of each individual school and support is based around the five areas of Mastery Readiness, also called the Catalysts of Change.

These catalysts are:

- vision and shared culture

- mathematical mindsets

- subject expertise

- systems

- and arithmetical proficiency

In this blog, Nicola, Doug and Laura reflect upon and share some of the things schools this year have done to drive improvement and really prepare for the next step in their journey to teaching maths using a mastery approach.

Vision and shared culture

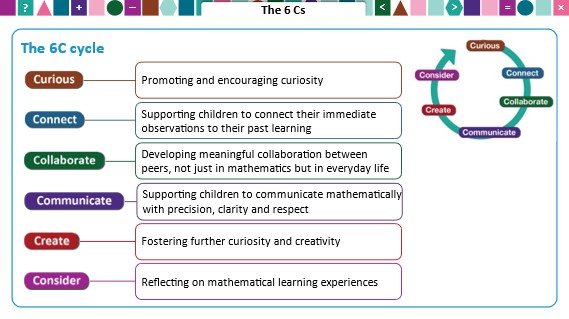

Although there is no strict hierarchy within the five catalysts for change, our first workgroup is always based around vision and shared culture as this acts as the driver which then leads into all of the future work that the schools go on to do.

School visions this year included:

Delivering an engaging and challenging curriculum, embedded with practical and fun activities which enable all learners to achieve and be successful.

For all children to have the secure mathematical knowledge for their next stage in learning and life. To instil a love of maths for all pupils.

To achieve teaching and learning where the whole class can work together regardless of age gaps. Teachers understand how to teach the curriculum across more than one year group in a practical and enjoyable way.

Each school in the work group brings its own unique context and this is reflected in their vision. However, there are many commonalities and one of the most common elements has always been that desire for all to enjoy maths and achieve their full potential.

Mathematical mindsets

The intended impact of exploring Mathematical Mindsets is to instil a ‘We are all in this together’ scenario where the profile of maths is significantly raised and is valued by all stakeholders across the school. This positivity increases the aspirations of all concerned and creates an atmosphere where success is recognised in many forms and equally celebrated. Working in this atmosphere allows for a sense of purpose and belonging. Growth becomes the customary central focus that is recognised as being achievable by everyone involved.

Starting points for developing this type of mindset were based on the outcomes of the Mastery Readiness self-evaluation that was carried out by each school in the first workshop.

Considerations included:

- Do all staff understand that classes contain previously high / mid / low attainers, but they do not limit the achievement of all pupils through labels such as ‘most able / less able’, ‘good / no good at maths’ and ‘can / can’t do maths’?

- Do all staff proactively promote a ‘can do’ attitude to mathematics for all pupils through a set of ‘positive norms’ for the mathematics classroom, including the use of ‘yet’, depth of understanding before speed and valuing learning by mistakes?

- Do all staff believe all pupils can and will achieve in mathematics?

- Do all staff encourage an inclusive ‘learning together’ culture? Do all pupils feel a sense of belonging in the mathematics classroom?

The answers to these questions were graded between 0 and 3 on a scale from being ‘currently not a feature of practice’ to ‘a central feature of practice’.

This provided key personalised information for each school and prioritised actions could be formulated based on specific evidence explored with the project team.

In Tewin Cowper C of E Primary School, this reflection led to the realisation that a change to mathematical mindsets would be a key aspect in the school’s journey towards teaching using a mastery approach. Both the Headteacher and the subject leader for maths articulated that the school had a vision and set of aims but this subject specific aspect had not been considered previously. Developing positive mathematical mindsets would form a sound foundation for the enhancement of pedagogy throughout the school.

When the Mastery Readiness Lead discussed the next course of action with the subject leader, it was realised that, from a leadership point of view, it would be beneficial to include all of the staff in the process and an effective starting point would be to create a Mission Statement. This would be the ‘driver’ for the rationale of a positive mathematical mindset and would guide the attitudes and consequent actions of all staff through the realisation of its potential impact, especially on the children.

The project team held a staff meeting to discuss and analyse the idea in depth and a whole school Mission Statement was created. This was deemed to be,

“Inspiring the Mathematician in everyone by championing enquiring, investigative minds.”

The content of the statement was developed through analysis of specific words and statements that staff agreed as being important.

The next step was to utilise the Mission Statement as the driver for the school’s actions moving forward.

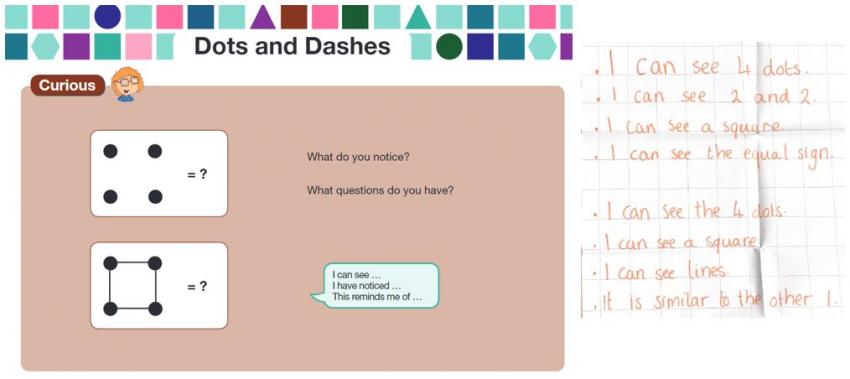

It was decided that an explorative approach in lessons should be introduced to staff. This would begin using the ‘Distributive Leadership’ model with the subject leader using the approach in her classroom and feeding back to teachers regarding the impact in a staff meeting. Staff then trialled the approach themselves and evaluated the process.

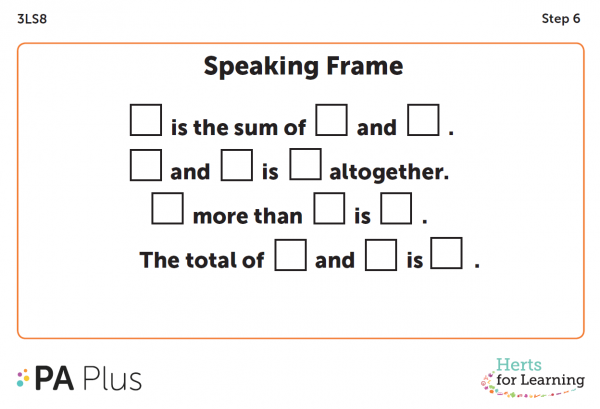

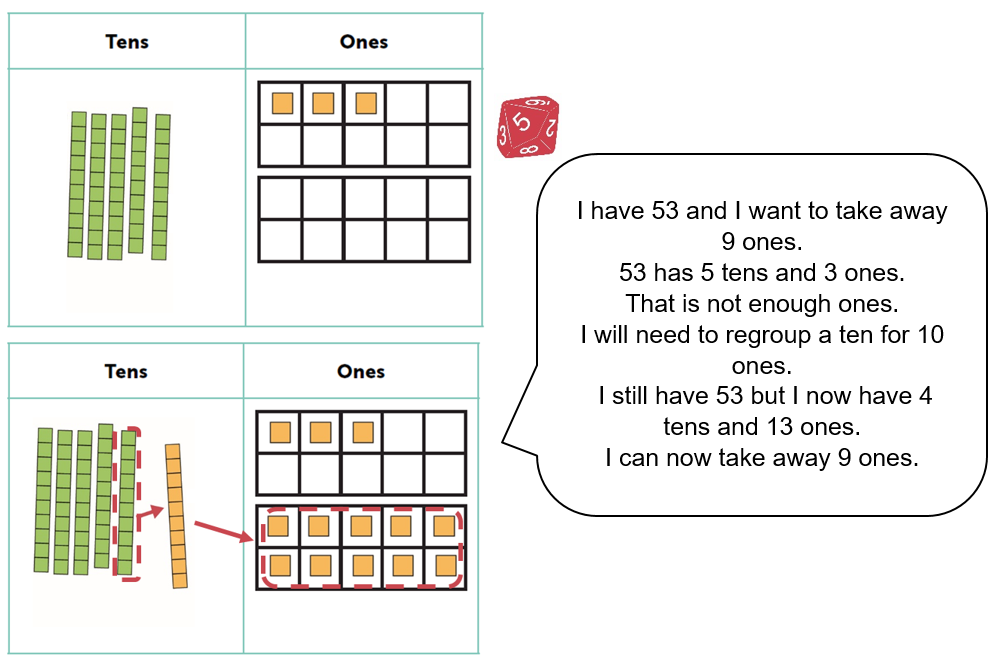

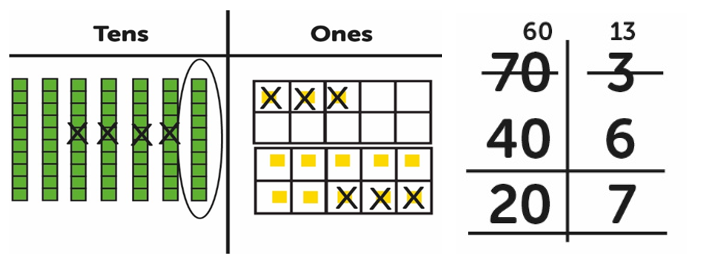

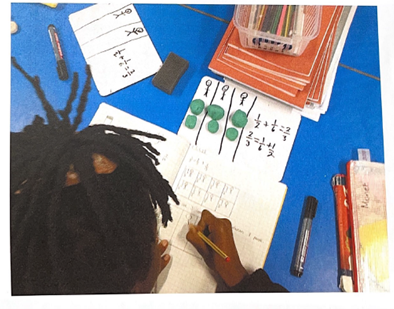

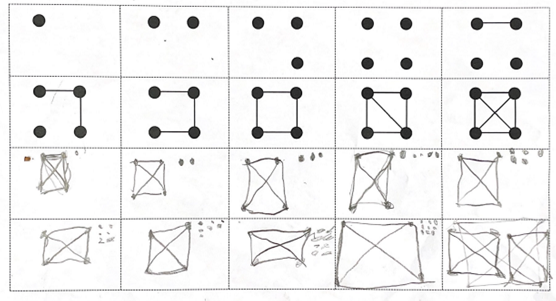

The staff meeting also included the exploration of a ‘low threshold entry – high ceiling’ approach to keep the class together and provide opportunities for constant formative assessment by the teacher. This was delivered with a focus on the use of the Concrete Pictorial Abstract (CPA) approach as scaffolding for learning and specific exploration by the children with a focus on mathematical talk and the use of specific language. See this blog to read more about the CPA approach.

The project team learned that there were:

Opportunities for children to learn as a whole class

There is ‘space not pace’ for learning and going slow meant children were able to make connections to previous learning. This meant that children began new learning from a more level ‘playing field.’ Children were demonstrating that they could use alternative / their own methods and sharing verbal reasoning. ‘Low threshold/high ceiling’ meant all children are able to access the level at their own level and self-challenge, thus less requirement for adult instruction. Discussions mean that children are using rich mathematical vocabulary.

Opportunities for formative assessment

All teachers reported that there was bountiful opportunity for assessment with one teacher commenting, “Amazing assessment –they knew more than I thought!” Teachers reported that the freedom of it allowed them to make informed judgements of when to move children on within the lesson. Lots more discussion and exploration meant teachers could move around and challenge verbally. Discussion revealed children’s level of understanding of concepts and mathematical vocab. This formative assessment also allowed for teachers to use day by day planning and be flexible.

Opportunities to change mindset

Lots of teachers reflected that children were sometimes confused by the expectation that they take a more active role. Children were starting to take more ownership of the learning. Things that appeared initially to be obstacles to the teaching e.g. “Children are used to digital clocks, not analogue” provided rich discussion.

At the end of the Mastery Readiness year, the project team revisited the self-evaluation to re-grade the statements.

It was clear that significant progress had been made and there had been a definite positive shift throughout the school. This was evident not only in classrooms but also from the general atmosphere in and around the school. The project team asserted that clear foundations had been laid, which were based on deep understanding of the catalysts for change to enhance mathematical mindsets through the ‘driver’ of the Mission Statement and the main theme of Vision and Shared Culture.

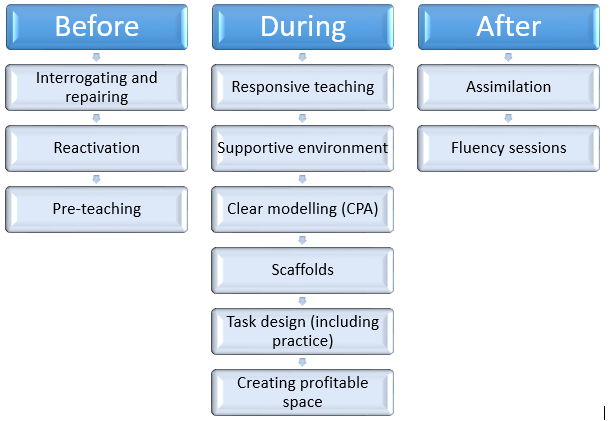

Systems

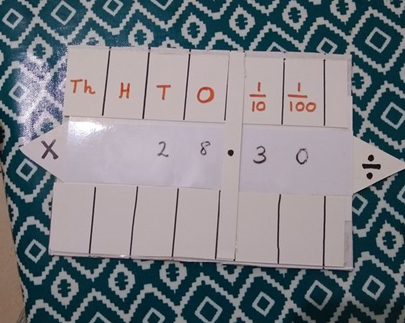

Within the ‘systems’ element, schools consider their overall curriculum provision for mathematics.

- Is maths taught daily?

- Are medium term plans sequenced coherently?

- Are systems in place to support the cycle of both formative and summative assessment?

Schools were supported by their Mastery Readiness leads to explore these areas and to prioritise actions. The project team, with the support of the Headteacher, then led and managed any changes made so that ownership was fully with each school.

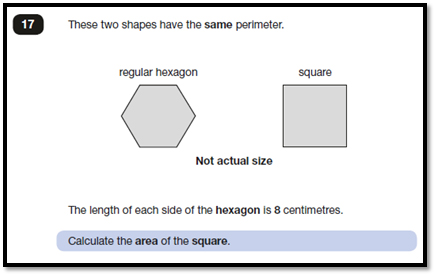

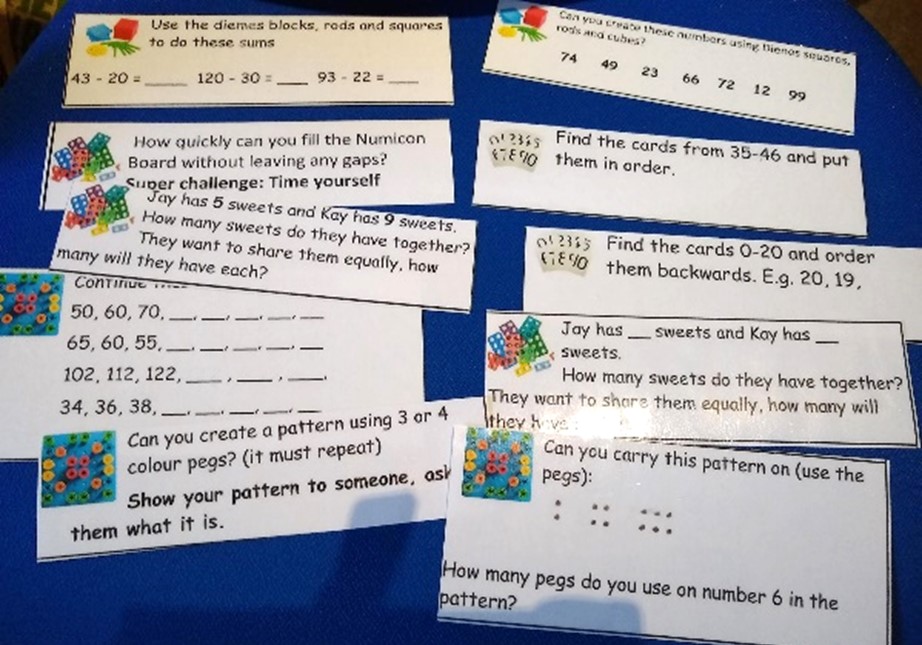

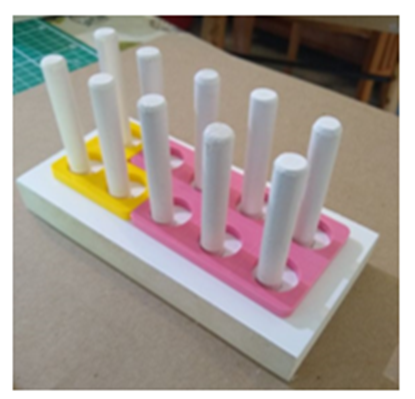

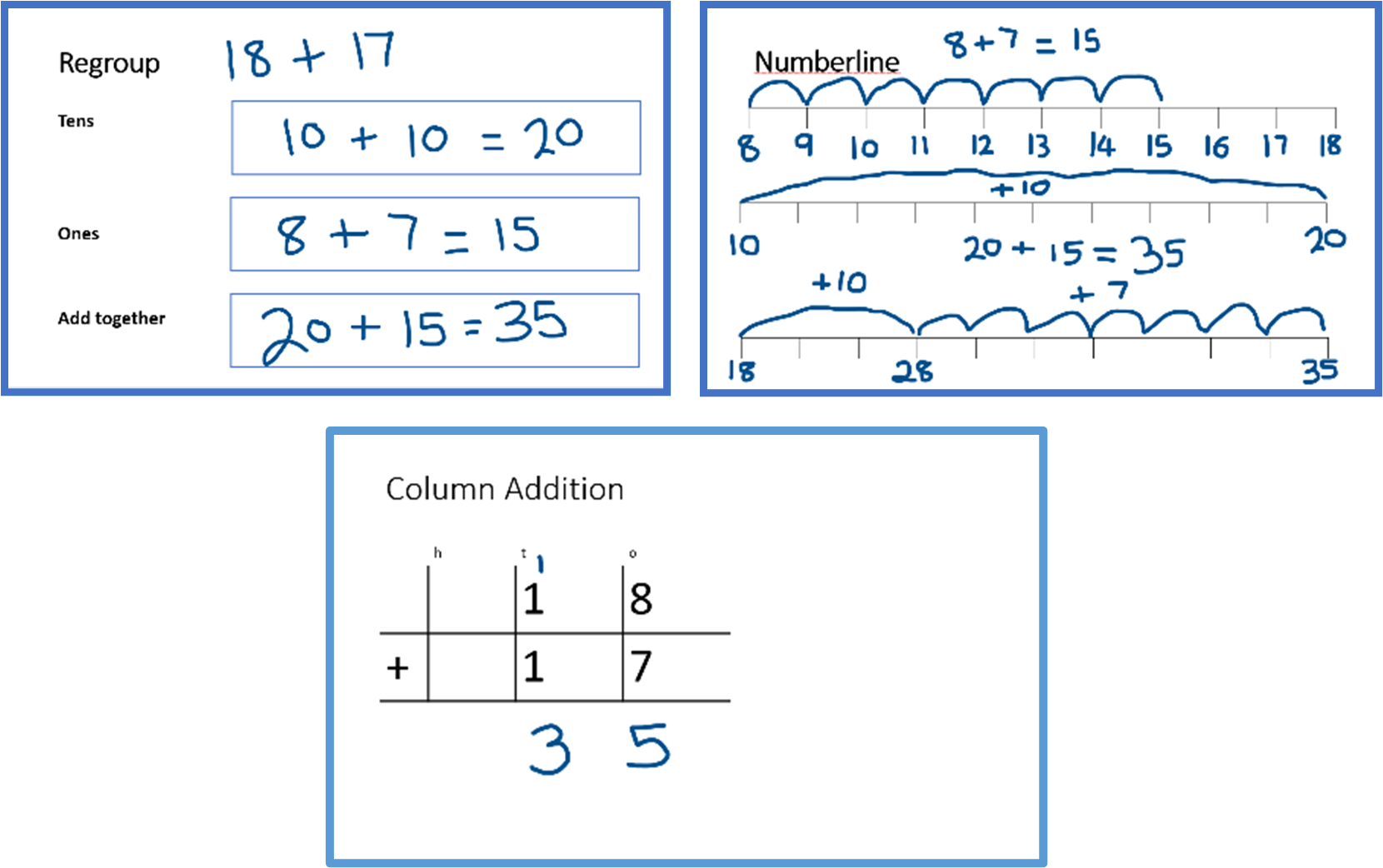

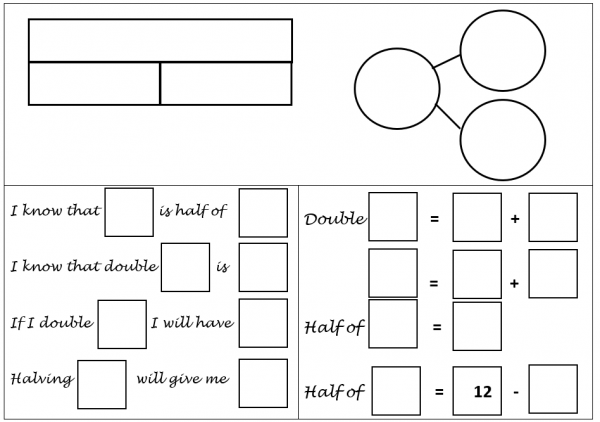

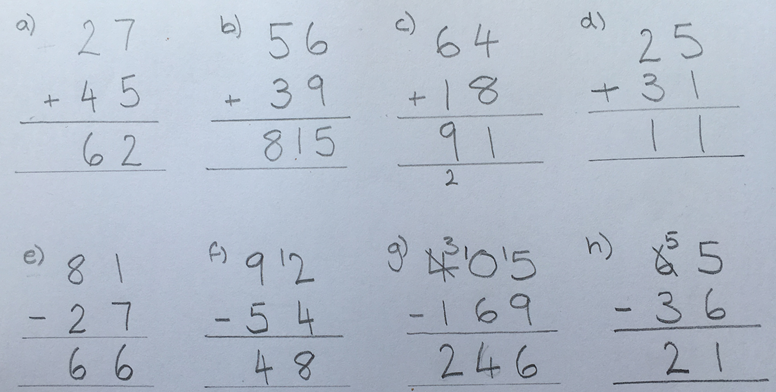

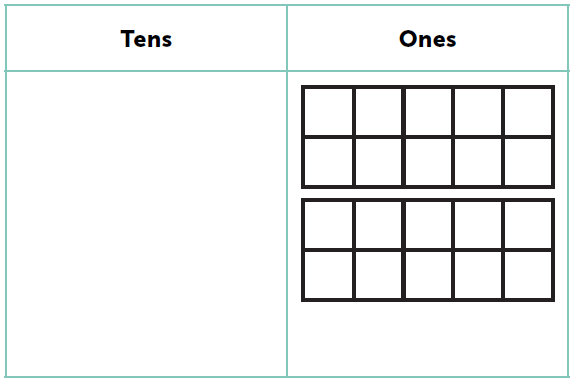

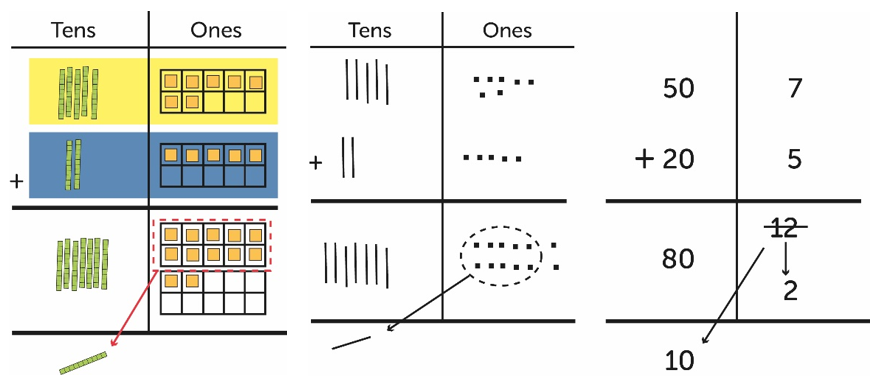

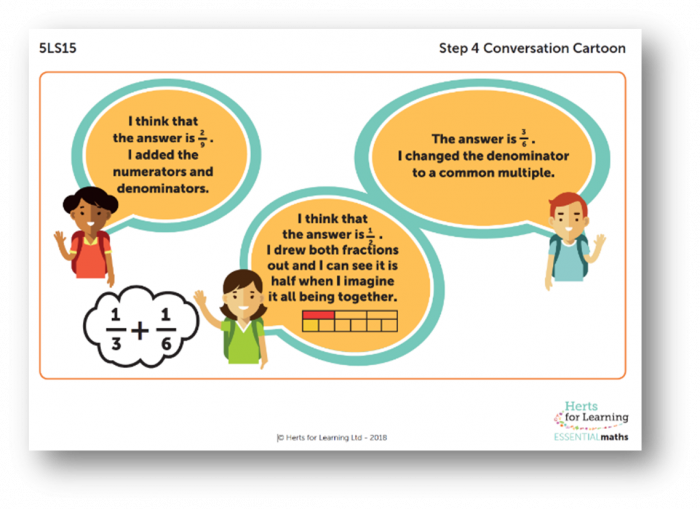

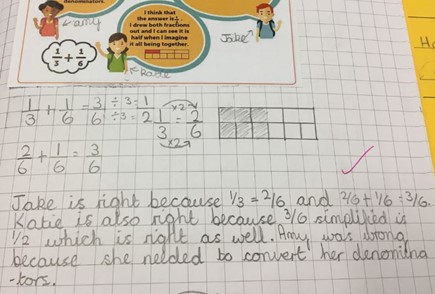

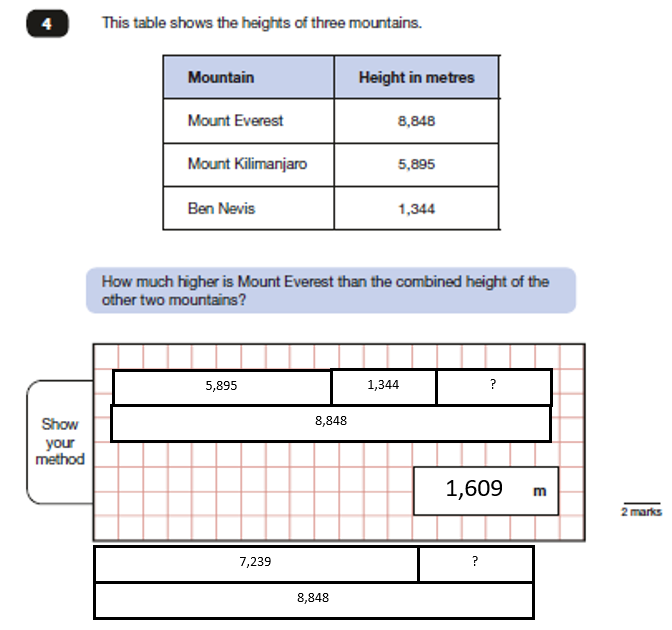

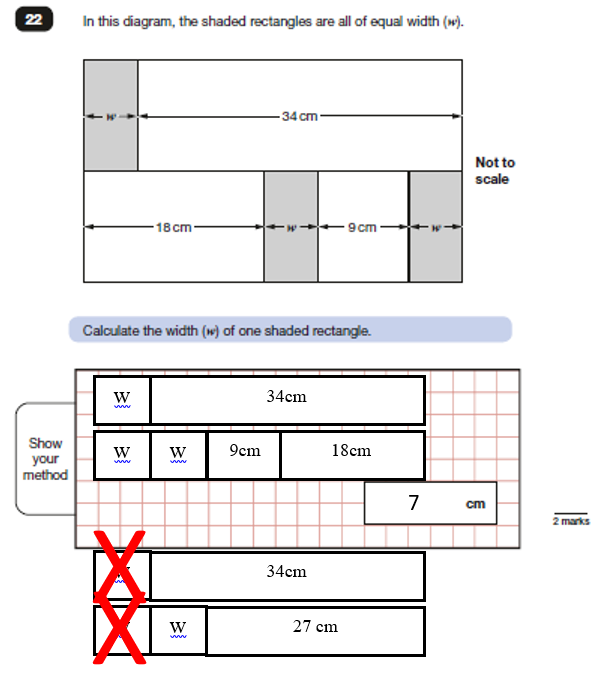

A key priority for Bedmond Primary Academy was to consider how to structure teaching in small steps, incorporating the CPA approach to develop secure understanding of mathematical structures and processes.

To do this, they began by visiting a local school to share strategies. Following this, they decided to purchase a set of planning materials that would provide small step sequences of teaching across the school and modelled examples throughout to ensure consistency across the school and continue to develop subject knowledge and expertise.

The project team then trialled the resources in their classrooms before enrolling staff on training for the autumn term. Teachers reflected that by participating in the training, they felt more familiar and confident with using the resource in their classrooms. As part of the implementation process, potential barriers were also considered, with the project team discussing lack of previous exposure to some of the models and representations that children would explore as well as heightened language expectations.

The careful consideration to the implementation process helped give the school a clear vision and plan moving forward this year to develop their planning and teaching, as well as the use of purposeful summative assessments.

Diagnostic assessments have been introduced this year and early in the summer term, additional time was given to teachers to thoroughly analyse their outcomes. This knowledge was then used to inform and tweak medium term plans for the remainder of the year. The process also lead to successful and informative transition meetings enabling teachers to plan for a flying start from September. The project team noted how useful this process had been and leaders have included the use of diagnostics, and time to complete detailed analysis, as part of their assessment cycle moving forward.

For more information: ESSENTIALmaths planning and diagnostic materials

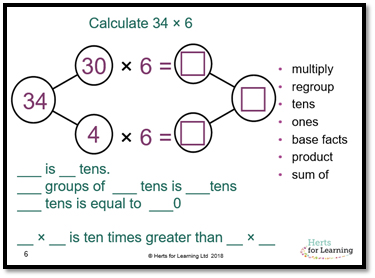

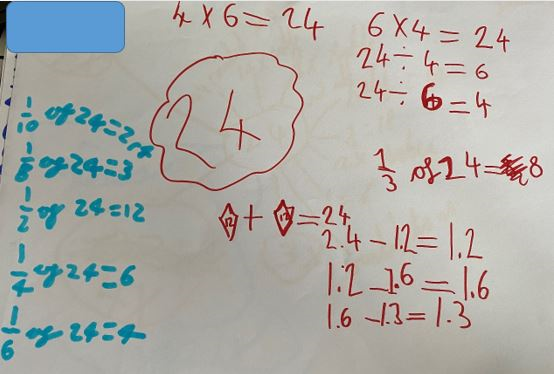

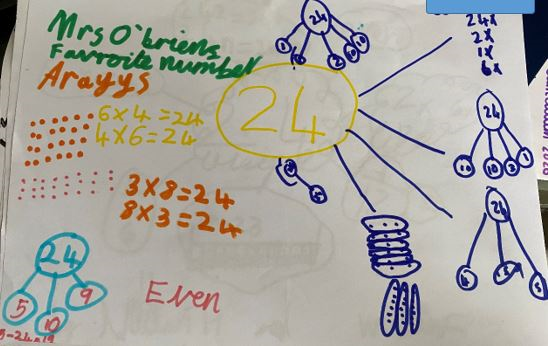

Arithmetical proficiency

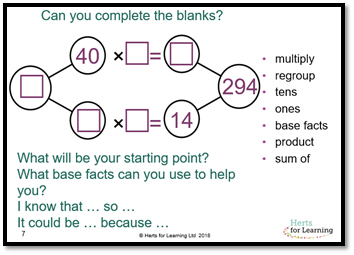

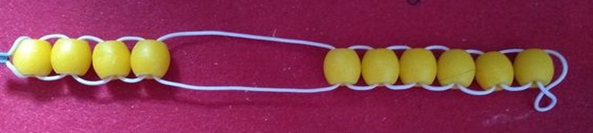

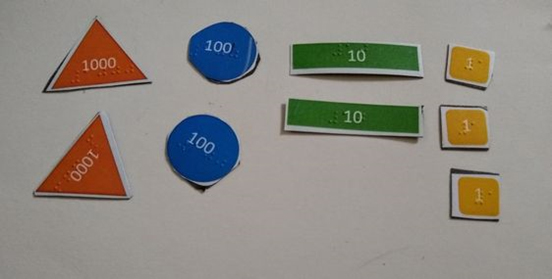

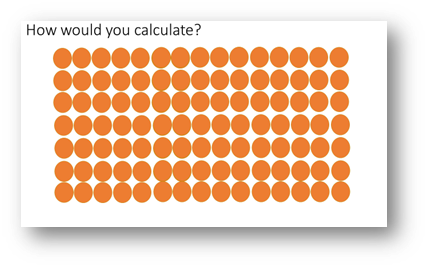

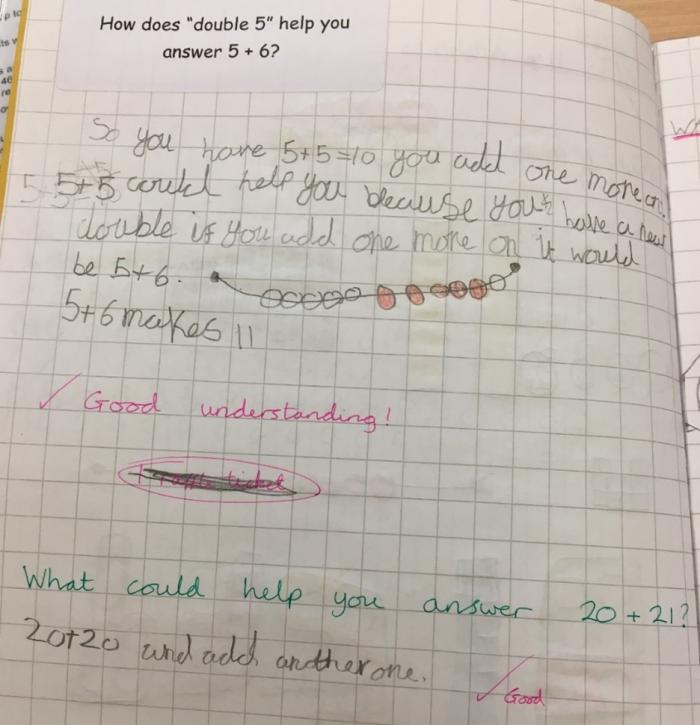

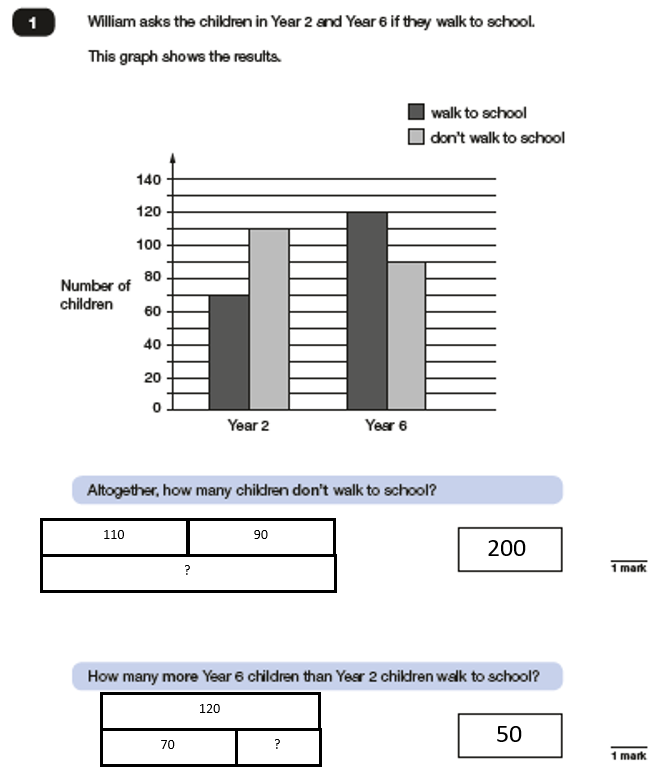

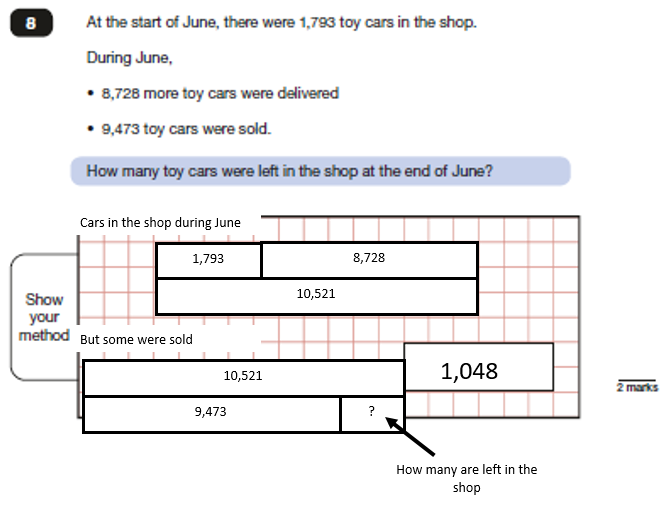

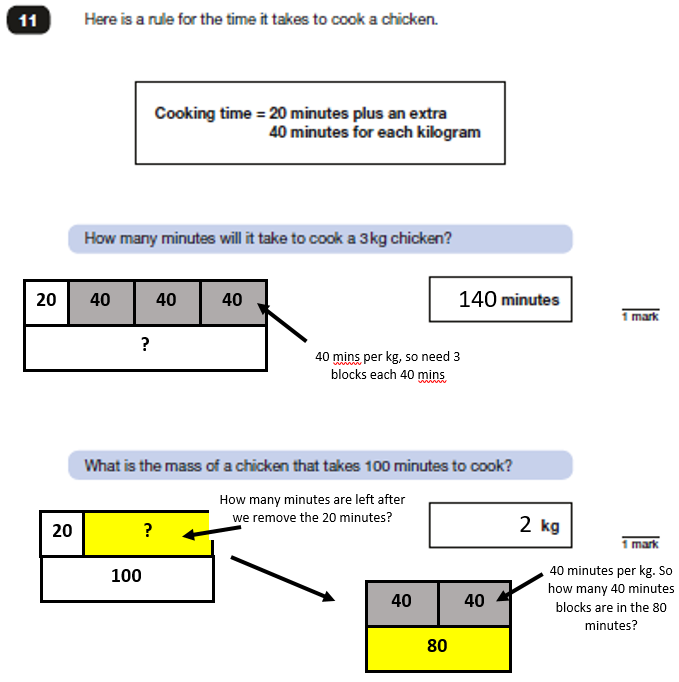

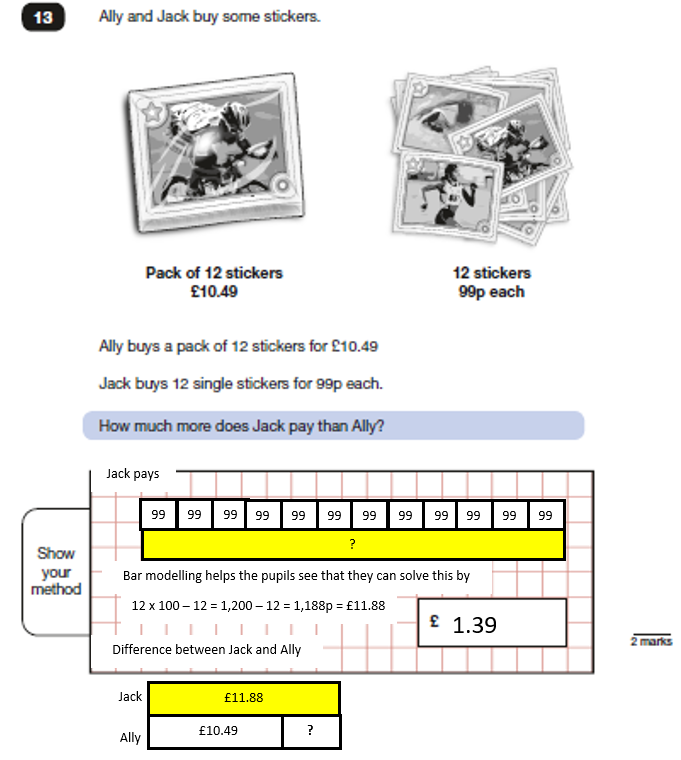

In order to successfully reason mathematically and solve problems, it is important that children are also proficient with their arithmetical skills and this is why two workgroups this year were dedicated to this catalyst; the first focusing on additive knowledge and the second on multiplicative.

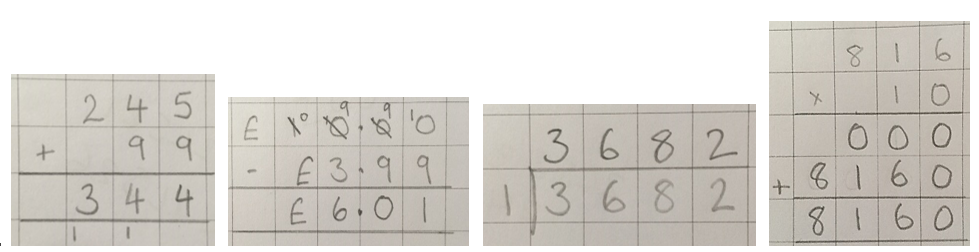

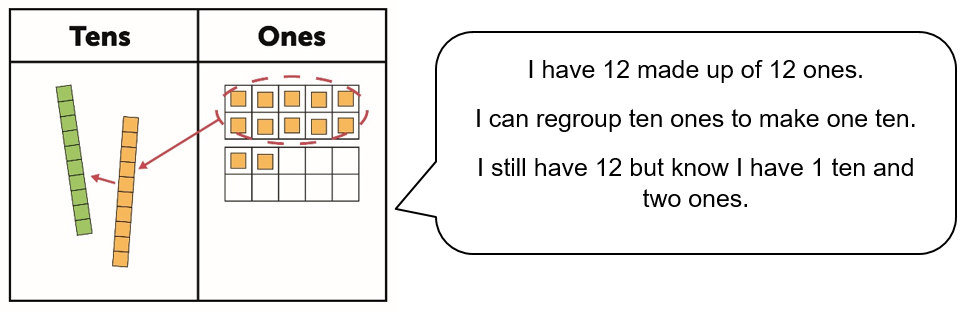

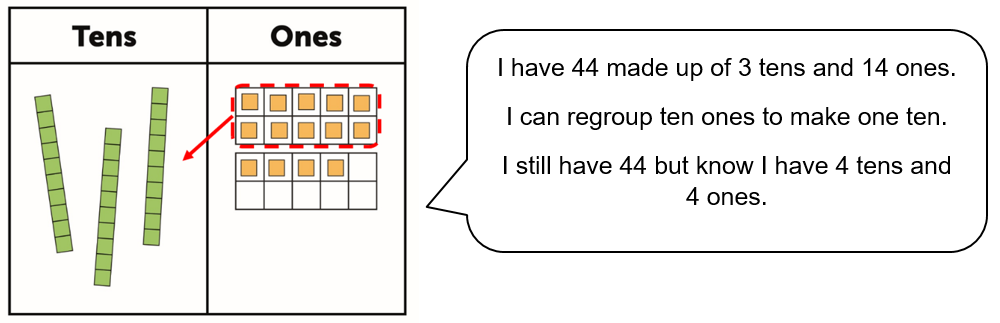

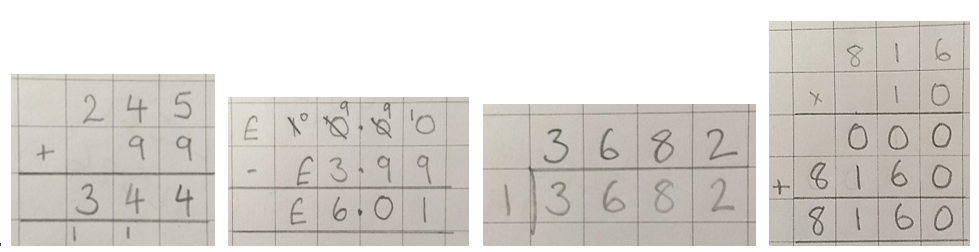

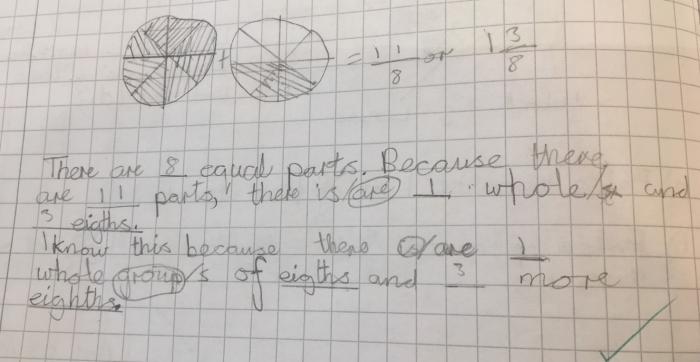

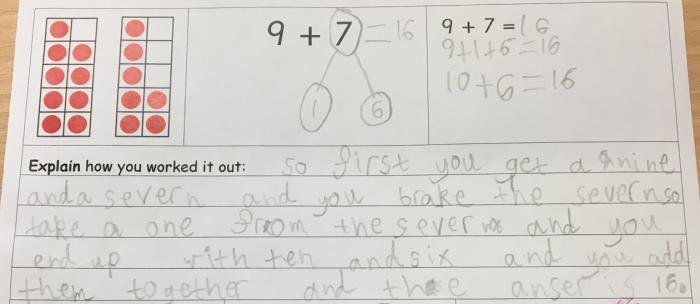

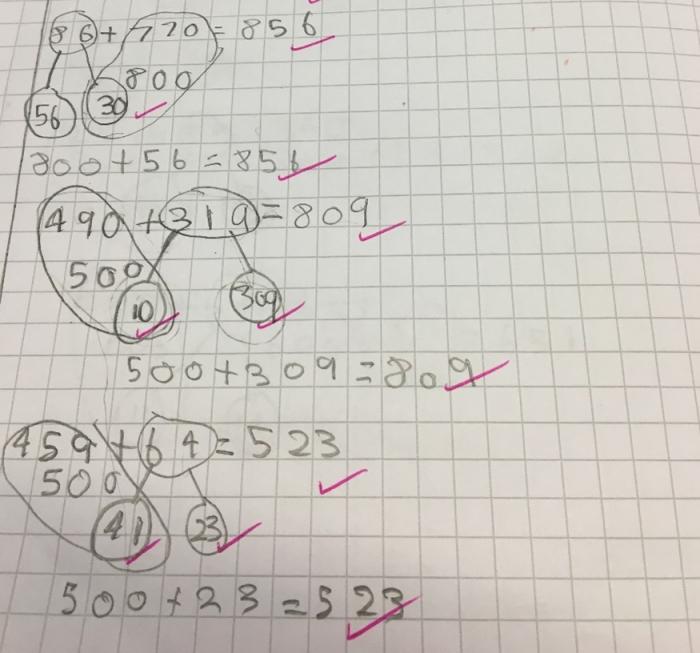

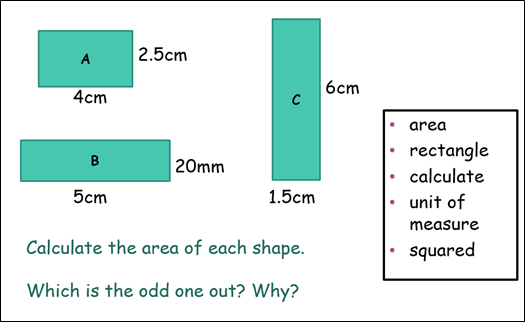

Three characteristics that underpin arithmetic proficiency are accuracy, efficiency and flexibility.

Accuracy involves pupils having secure knowledge of their number facts, making meaningful recordings, applying their knowledge of relationships between numbers and double checking their results.

If efficient, children will be fluent with a range of calculation strategies with the ability to choose their method based on the calculation they are tackling.

Pupils with flexibility are able to move smoothly between different strands of maths. They have more than one approach and are able to choose and carry out an appropriate strategy.

This was something that Cassiobury Junior School were keen to explore as, although many of their pupils were competent when using formal written methods, there was less flexibility and efficiency in terms of the methods chosen, with pupils often over-reliant on those written strategies.

Another area for development that the project team had identified was that pupils were less confident at recalling prior learning when needing to apply it to real life problems and scenarios.

The school decided that in order to provide pupils with additional opportunities to revisit taught knowledge and skills, and to encourage discussion about multiple strategies, that they would introduce fluency sessions.

To support staff with planning and resourcing these sessions, the school purchased the HfL fluency session slides which revisit taught concepts and are then used on a regular basis to establish familiarity and understanding and increase confidence for all.

The project team trialled the sessions in their classes and reported that, even after only a week, pupils were participating more confidently using precise mathematical vocabulary and discussing their reasoning with peers. And pupils reported how much they enjoyed the sessions! The project team planned to introduce the sessions and resources in a staff meeting during the summer term ready to fully implement them into their weekly timetables in the autumn term.

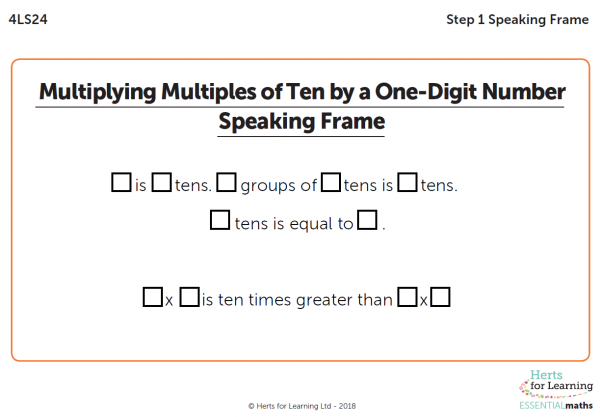

To further support the school’s priorities around times tables recall and multiplication strategies, teachers will include a slide with a multiplication focus and a mental strategy element in each of their sessions so that key number facts are regularly rehearsed.

Therfield First School also focused on developing fluency sessions in their mixed-age school as part of their Mastery Readiness year. Read more about their journey here: Children are seeing themselves as mathematicians – the impact of CPA and fluency sessions in my mixed age class

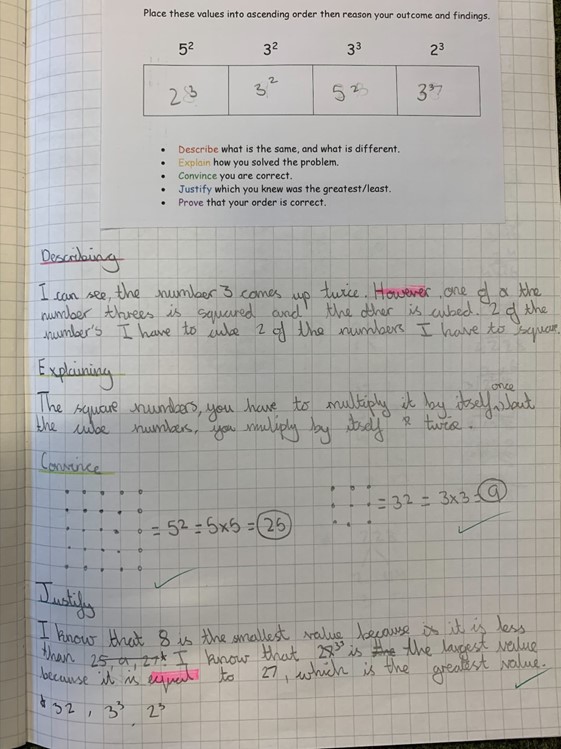

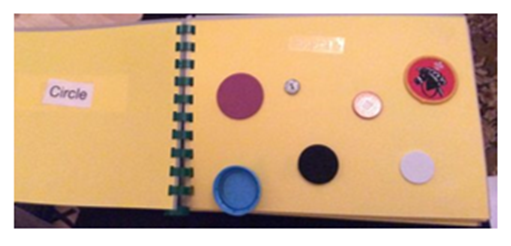

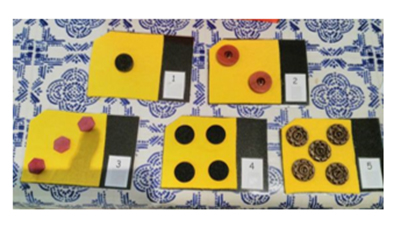

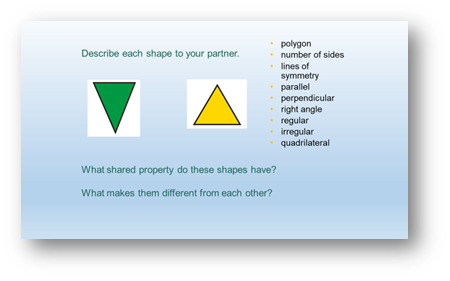

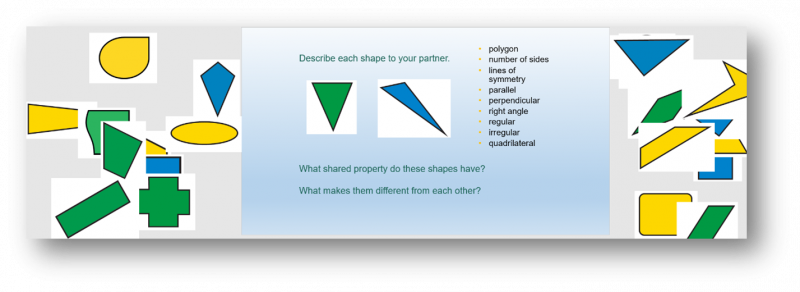

Subject expertise

Last, but by no means least, comes subject expertise. Secure subject expertise and pedagogy for both teachers and teaching assistants is essential in developing mathematics. Knowing the age-related expectations and the necessary building blocks to get there is key to all children keeping up. It is important that children explore and learn about mathematical structures through concrete and pictorial representations. For children who find it difficult to articulate their thinking, this will support them to develop that and also allow teachers to pick up on any errors or misconceptions.

This year, with the disruption to schooling, it was more crucial than ever to be able to identify the starting points of the children in each concept and to do this, teachers needed to be aware of each small step in the sequence of learning.

Tannery Drift First School found gaming to be a valuable tool for identifying these starting points following the national lockdown in spring 2021.

Knowing how important it is for children to have a variety of calculation strategies in their toolkit, the Year 2 teacher wanted to check which strategies were being commonly used for addition and subtraction and whether or not the children were recalling number facts automatically in the process. Information gathered from observing and interacting with children playing games was then fed into teaching plans going forward.

The Year 4 teacher thoroughly enjoyed the designated gaming sessions and the children did too. As the games were played more than once, things could be dripped in over time and opportunities could be taken to support development of language or stretch thinking based on what was being observed. This was particularly beneficial for the teacher in the parallel Year 4 class who was new to the school as it provided opportunity to get to know the children in a very low-threat and fun environment whilst also highlighting areas of strength and areas that would require further teaching.

The children not only enjoyed playing the games provided, they began to design their own. For example, in Dodge the Crocodile, they thought about how to ‘trick’ players by including common misconceptions and errors on their path. Enabling the children to do this relied on the teacher’s strong subject expertise.

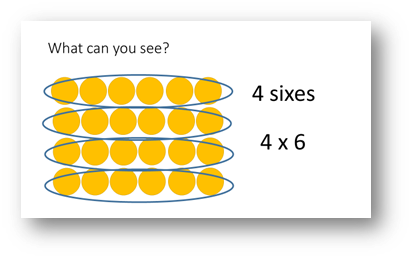

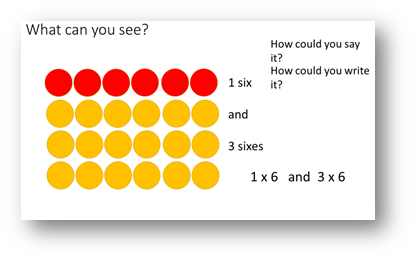

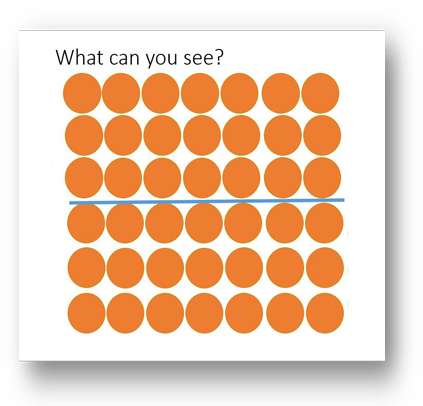

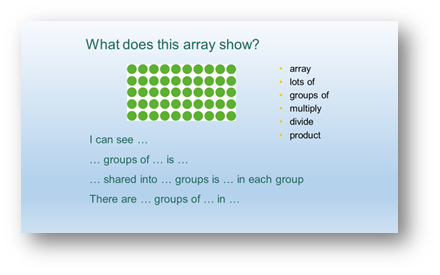

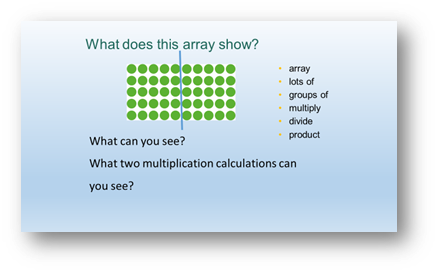

Collaborative planning is an approach the school have been using to plan the progression across the school in the teaching and rehearsal of times tables. Following workshop 3 around multiplicative reasoning, there has been a whole school focus on the recall of known multiplication facts and strategies to work out unknown facts.

Exploring the structure of multiplication with the children, along with modelling the use of accurate language, has enabled them to articulate their strategies for working out unknown facts. Both project teachers have noticed a big difference in the way their children play with numbers to reach unknown facts.

Year 4 have been working on the 12x table and focussing on understanding of mathematical structures.

- Can we partition it?

- Could we use double the 6x fact?

- Could we use 10x and 2 groups more?

Teaching happens as a whole class to secure understanding and then game choices are provided for rehearsal.

Thank you to those schools who shared their journeys so far in this blog.

For more information about Mastery Readiness and to apply, please contact primarymaths@hfleducation.org.

Blog authored by Laura Dell, Nicola Adams and Doug Harmer.

Our school’s previous Ofsted report noted that the next steps and ongoing focus should include attention to ensuring that ‘higher-attaining pupils are consistently challenged by all adults, so that they achieve the very best they can in writing and mathematics’.

Our school’s previous Ofsted report noted that the next steps and ongoing focus should include attention to ensuring that ‘higher-attaining pupils are consistently challenged by all adults, so that they achieve the very best they can in writing and mathematics’.