The natural world is a treasure trove of beauty, wonder and ingenious design and we don’t have to travel to warmer climates to discover this. Nature is right here on our doorsteps!

Moreover, there is an increasing body of evidence which shows that engaging with nature and the outdoors is good for both our mental and physical health. In other words, children need nature and nature needs children too. It needs children to be guardians of the natural world: supporting children to connect with nature is an important part of this. As Sir David Attenborough says:

"No one will protect what they don’t care about; and no one will care about what they have never experienced."

This blog contains activities, plants and animals to look out for, and resources to help children connect with, and ultimately champion, the natural world. This can start with something as simple as recording their observations in a nature diary, just like many scientists do now. The National Trust have included this as one of their 50 things to do before children reach 11 ¾!

Five ways to explore and connect with nature:

1) Flowers and blossom

Spring and early summer is the perfect time to ask the children to take a close look at some of the flowers that are in bloom (including tree blossom). Encourage them to draw pictures to show the detail of the flowers to promote careful observation.

Questions to ask children:

- what shape are the petals?

- how many petals are there?

- what colours can you see?

- what is inside the flower?

To help name some of the flowers and blossoms you may see, use this blossom spotter sheet or this Spring flowers ID sheet from The Woodland Trust or try the Plant Life website which shows which wildflowers to look at each month.

Linking with maths, children could try and find an answer to the following questions:

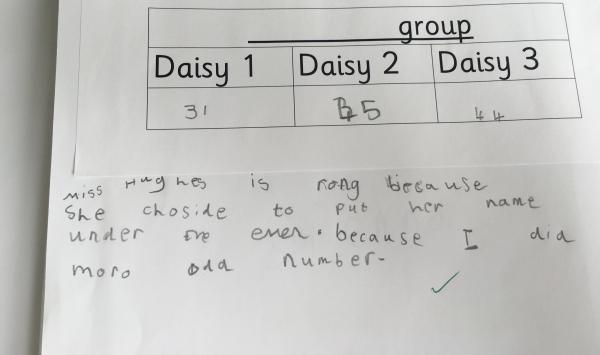

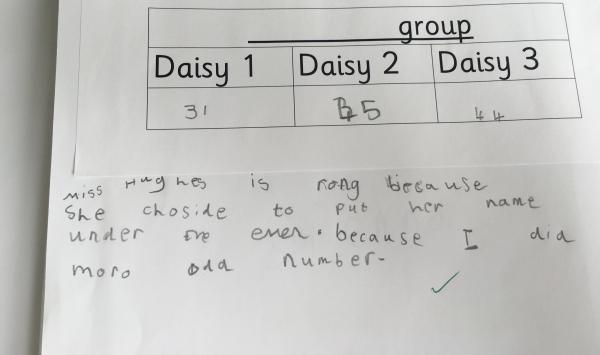

Do flowers always have an even or odd number of petals?

Do flowers of the same plant always have an even or odd number of petals?

Here is an example from a Year 1 child investigating this question with daisies:

Fascinating plants: some flowers like daisies close at night and open back up during the day. There are a range of flowers that do this such as dandelions, tulips, poppies and buttercups. Encourage children to look at them in the evening, early in the morning and during the day to see if they can spot the flowers opening and closing.

2) Bird spotting

Many people find watching and listening to birds a peaceful and relaxing pastime. Over a million people took part in the RSPB’s annual big garden birdwatch in January. It is one of the biggest ‘citizen science’ events and helps scientists and conservationists understand what is happening to bird populations. If you missed it this year, you can still access the results and it is worth putting the date in the school calendar or diary for next year.

Did you know that, as a nation, we spend more on bird feed than any other European country? Scientists think that this has caused the length of blue tit beaks to become longer over time (an example of evolution)! The RSPB has some simple instructions for making bird feeders from items in our recycling bins and a few twigs. Why not get children to make a bird feeder and then record the birds that come to visit it? The RSPB also has some simple instructions for making a bird bath that might attract blackbirds, robins, woodpigeons, sparrows and starlings to come for a quick dip - a great addition to a wildlife area.

It is useful to remember that birds are often easier to hear than they are to see and listening to bird song is also incredibly relaxing. Children could use the Woodland Trust’s bird song identification resource to try and identify some of the songs and calls of birds that they hear.

3) Insect hunting

Going on a bug hunt is a favourite activity of many a child (and for good reason too): we have a range of beautiful and intriguing invertebrates.

Here are a few of my favourite ‘bugs’ to look out for:

Worms

There are lots of different methods for bringing worms to the surface without digging up the school field or garden (although you can do this too). Worms like moist soil so if you have anything lying on the ground such as plant pots or stones, carefully turn them over to see if you can find any there. You could also try making vibrations! This is sometimes referred to as worm grunting or charming and it is thought that some vibrations mimic the sound of moles, a predator, which send them hurrying up towards the surface.

Children can be encouraged to look closely at their worm (once found), its features and how it is moving. They often enjoy giving it a name and drawing it.

Questions to ask children:

- how long is your worm?

- can you tell where its mouth is?

- how does it move?

- what is its body like?

Encourage children to come up with their own questions and see if you can find the answers together. For more information, watch a clip from Spring Watch on the Amazing World Of Earthworms and check out the National Geographic website. If your school is a CLEAPSS member, there are instructions on the primary website for making a wormery which would be a great extension to this activity.

Ladybirds

Ladybirds are a favourite of many a child. Children can record how many spots each ladybird they find has, and what colour its head and body is (this differs according to which species they are). The Woodland Trust have a great nature detective sheet to help children identify the ladybirds they find.

Once children have spotted adult ladybirds, they can then look out for ladybird eggs. These will be clusters of small golden eggs on the underside of a leaf. Eventually, the eggs will hatch, and children will be able to spot ladybird larvae. The larvae are much easier to spot than eggs as they are quite active when they are feeding and growing. The larvae then eventually become pupa as they metamorphose into the adult form (the ladybird as we know it).

This photo shows two pupae from my garden last year. They stay like this for up to two weeks. If you find some, encourage children to take a picture every day to see how they are changing.

For more information about the ladybird lifecycle, check out the BBC website or this ladybird life cycle iDial from the Woodland Trust.

Woodlice

Woodlice can also be easily found in damp and dark places. Children could think about where they might find these conditions, in the school grounds or their gardens, and then go on a woodlice hunt! They can carefully collect some to take a closer look at how they are similar to (or different from) each other. There are 30 species of woodlice that can be found in the UK, so they may find different species. One species, sometimes called roly-poly or pill bugs, are able to roll themselves into a ball as a defence against predators.

The children could investigate which material woodlice prefer to live under by placing small squares of material (plastic, paper, card, carpet) on to bare earth and leaving them for a couple of weeks. They can then go back and count how many woodlice they find underneath each material (an added bonus being they may also find some other invertebrates).

An interesting fact to share with children is that woodlice are actually crustaceans that live on land! This means they are more closely related to shrimps and crabs than insects. Children could look at pictures of crabs and shrimps and think about how a woodlouse is similar or different to these.

Butterflies

Butterflies are always a welcome sight. Did you know that the UK has 59 species of different sizes and colours?

Why not ask children to spend some time looking for butterflies and draw pictures of those they see before using the Butterfly Conservation website or this butterfly spotter sheet from the Woodland Trust to identify what they find.

Bees and bumblebees

It is important for children to see and understand the essential role that bees and bumblebees play in pollination. They can do this through close observation, as it is possible to spot them drinking nectar from flowers and transporting pollen on their furry bodies. Children may even be able to spot a pollen basket which is a structure on the hind legs which certain species use to harvest pollen.

The Bumblebee Conservation Trust have a range of educational activities and Friends of the Earth have a good identification guide for older children. The much- loved TV presenter, Maddie Moate, is also a beekeeper and has a series of videos on YouTube in a series called Beekeeping with Maddie.

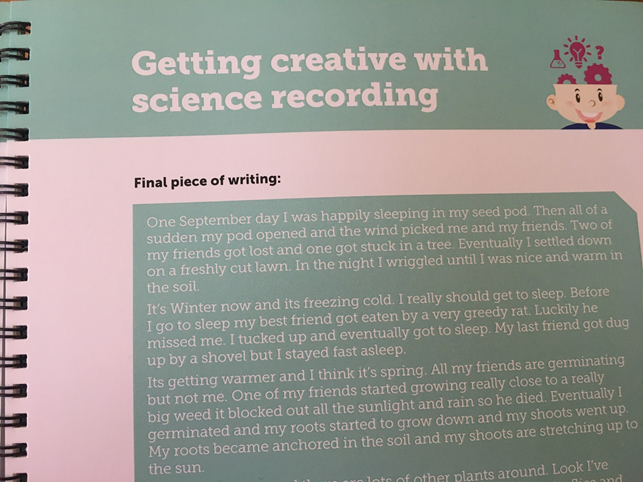

While searching for invertebrates, children could think about entering the annual ASE Great Bug Hunt. Primary aged children have until the 10th of June to find a ‘bug’ and learn about it. They can share their learning in a variety of ways (producing posters, poems, stories or even a video). This is a great competition for encouraging first-hand experiences with the natural world, research and creativity.

4) Planting

Growing and nurturing a plant from seed brings joy and satisfaction and is a fantastic learning experience. Sunflowers are a great place to start, as they are relatively easy to grow (in the spring and early summer) and they provide opportunities for children to make observations and develop their understanding of plants such as:

- growth over time (height, number of leaves, bud formation and the flower opening)

- how the flowers follow the sun throughout the day

- bees visiting to feast on nectar and pollinate

- seed development

It is also hugely satisfying to grow and harvest plants to eat and is a great way to introduce children to new healthy foods. Take a look at Edible Playgrounds and the RHS Campaign for School Gardening for guidance and inspiration.

The NFU also have Farming STEMterprise projects where children can grow, design and market their own food products.

5) Books and documentaries

So far, all of the ideas and activities I have suggested provide children with first-hand experiences of nature. This is essential, as spending time outdoors in nature has many benefits.

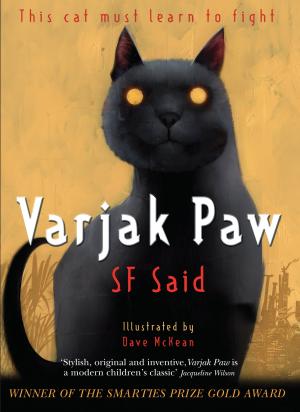

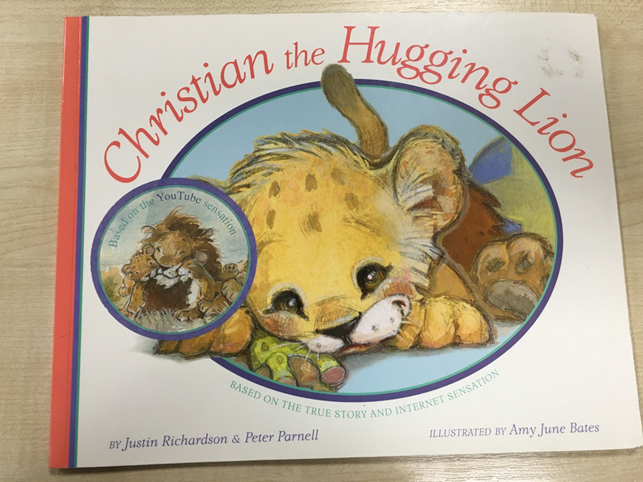

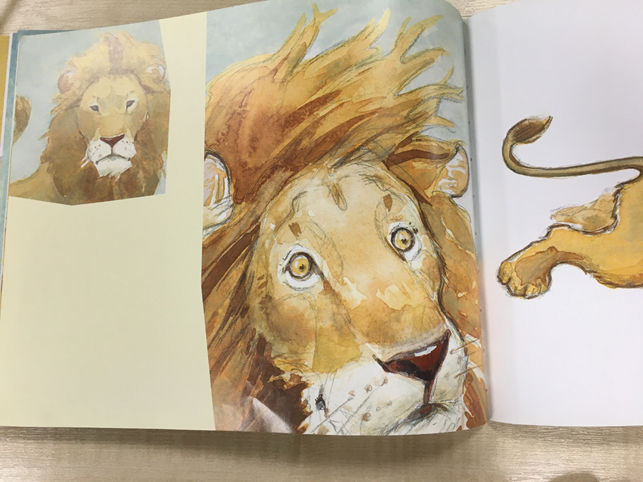

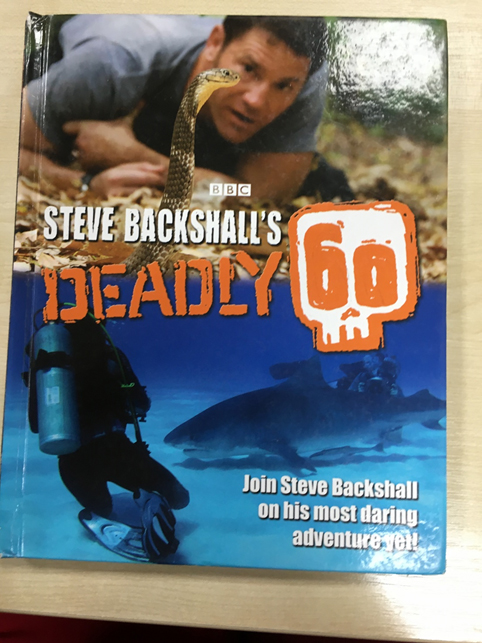

However, alongside these first-hand experiences, there are also opportunities to engage children with nature using books and documentaries that provide the opportunity to ‘travel’ to distant lands and habitats and gain insights into the natural world which are less easy to encounter first- hand. Here are just a few suggestions:

The benefits of engagement with the natural world to both our mental and physical wellbeing are well evidenced. What is less certain is the future preservation of the natural world. Perhaps by developing children’s scientific observation, understanding and ultimately love of nature, we will also be able to encourage future generations to nurture (and be nurtured by) the natural world in the years to come.

Please follow us and share your learning in nature with us on Twitter @Hflscience.

Why not sign up to receive our regular subject leader emails which are full of resources and ideas to support science learning.