It’s autumn, and while the Year 6 Reading SATs paper may feel like a distant memory, many of us already have our eyes on 2026. Looking back at the paper gives us valuable insight into how children are being asked to demonstrate their knowledge, stamina and comprehension. So, let’s take a closer look at the 2025 paper and reflect on what this means for classroom practice.

The extracts

Children faced explored the usual three extracts, with an hour to read and answer 50 questions:

- A Life-Changing Game - a biographical extract about Phiona Mutesi, who is a Ugandan chess prodigy.

- In the Cave - a science-fiction narrative where two boys discover a very strange machine.

- Longbow Girl - a historical fiction extract in which a young archer engages in a tense competition.

The extracts increased in complexity as the paper progressed; while extract 1 offered a relatively gentle start, extract 3 required stamina, inference, and close attention to language.

Content domain analysis

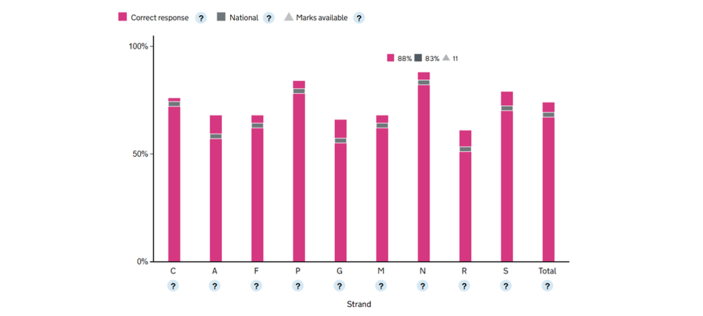

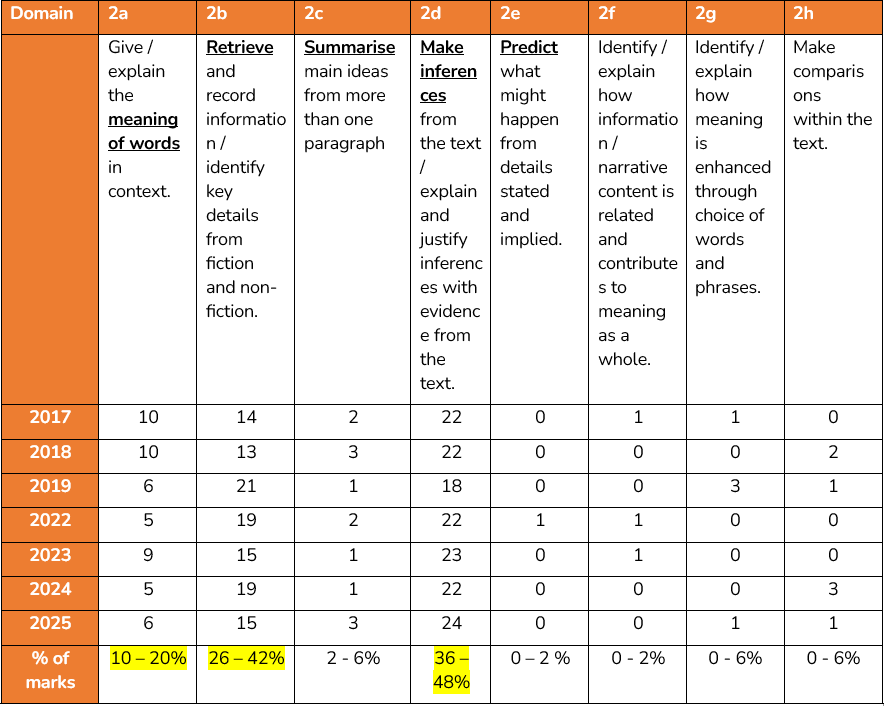

Unsurprisingly, inference once again dominated the paper. Almost half of the marks tested children’s inference this year, with a significant proportion of the rest of the paper focused on retrieval and vocabulary. Together, these three domains accounted for around 90% of the potential marks. This follows the usual trends. The table below provides you with a comparison to previous years:

These three domains are hugely significant for becoming a skilled reader, and much of our reading teaching should focus on developing children’s retrieval, vocabulary and inference skills. The other reading domains of course support the goal of comprehension and inference, and pupils should learn how to use and apply these comprehension strategies to build a mental model of the text. However, the 2023 Reading Framework is clear that these content domains should not be treated as a checklist for teaching reading. Instead, the framework reminds us of the importance of drawing on and weaving together a variety of strategies. When we read, we might be visualising, making predictions, and questioning – all to support inference - and often all at once. These processes are interconnected, not isolated skills to be ticked off a list.

Building on my previous blog (Reading SATs knowledge: Reading SATs power), a helpful next step is to give more attention to comprehension strategies that support children to become aware of their own thinking as they read. This means encouraging them to:

- monitor their understanding,

- notice when things don’t make sense, and

- connect new ideas with what they already know.

Encourage children to briefly summarise a paragraph after they have read it, or to note any questions in the margin of the text. Christopher Such explains this clearly in The Art & Science of Teaching Primary Reading (p. 60): ‘Research suggests that encouraging children to ask themselves questions about the text’s meaning and to summarise parts of the text can lead to improvements in comprehension. In addition, children can be taught to recognise when greater attention is required.’ This will aid children to grow into confident, thoughtful readers who can flexibly use their reading for different purposes.

A gentle start to a tough challenge

The first extract, A Life-Changing Game, gave children a fair start: a clear structure and a familiar non-fiction genre. However, cultural references to Uganda and the art of chess may have been more demanding for some children without the relevant background knowledge. We can’t prepare children for every possible eventuality, however, exposure to a rich, broad reading diet will help to power up children’s background knowledge and expose them to previously unfamiliar worlds and vocabulary.

The second extract, In the Cave, was more challenging. Children were faced with potentially unfamiliar vocabulary such as ‘beckoning’ and ‘inaudible’. The way that dialogue was used, while seeming simple at first glance, required children to keep up with the conversation as it revealed discoveries, built tension and moved the plot forward. The text was also littered with many long, multi-clause sentences. Children require plenty of practice in grappling with these; strategies such as re-reading, breaking them down into meaningful chunks, and visualising, can all help with making meaning from long sentences.

The final extract, Longbow Girl, was the most demanding. A historical fiction extract blending technical archery vocabulary along with figurative language and more of those long, multi-clause sentences - a real challenge for less confident readers. Children had to track the physical events, get to grips with the atmosphere and infer the characters’ emotions, which were sprinkled throughout. That’s a lot to balance! Inference requires the use of multiple reading processes at once. Rich dialogue about texts - in which teachers model making meaning by making connections, empathising, predicting, summarising, questioning, and children are invited to do the same – will support children to feel prepared when approaching texts of this pitch.

Reading fluency comes into play here, too. Without accurate, automatic reading and expressive phrasing, children can struggle to access and make meaning from lengthy sentences or layered passages. Fluent reading reduces the cognitive burden of decoding, allowing the reader to focus on understanding. To develop fluency, pupils require regular opportunities to read widely (a range of different texts) as well as deeply (reading the same text more than once). By doing so, they build their automaticity. They also benefit from hearing an expert model of reading and reading alongside that model (assisted reading); this supports application of prosody and phrasing which can help to make the meaning clear, paving the way for understanding. This is why reading fluency is often referred to as the bridge to comprehension. We have a number of blogs on the topic. Have a read of this one, which gives more insight into the research behind fluency and this one which explores how to teach fluency.

Precision over plausibility

This year’s mark scheme highlighted the need for accuracy, not just general understanding. Let’s dive into Question 3, which is based on A Life-Changing Game:

‘How can you tell that people in Uganda were not familiar with chess?’

At first glance, some answers may have seemed plausible but only the very specific ones were accepted:

‘There was no word for it in Phiona’s language.’

‘Chess was unusual in Uganda.’

‘She had to walk six kilometres every day to learn how to play.’

Responses such as ‘they didn’t know what it was’ or ‘they hadn’t heard of it’ were rejected. Why? Because they went beyond the text and were a little vague. The extract does not say nobody knew chess, only that it was ‘unusual’ and ‘there was no word for it.’ Children needed to tie their answers to the evidence given in the text.

Encouraging children to ‘prove it’ - ‘put your finger on it’, or ‘highlight the part of the text that tells you’ - is a simple but powerful way to build this habit. Train children to go back to the text.

Inference

As usual, inference sat firmly at the heart of the paper, with 24 marks testing this domain – even higher than in recent years. Children were asked to interpret motives, explain actions and describe character traits. Take question 37, based on Longbow Girl. Children had to explain why Merry smiled at the end of the extract. The reasons were scattered across the extract, and the mark scheme allowed several valid answers. This included her accuracy, her victory, the crowd’s respect, or proving others wrong. But to gain full marks, children had to give two distinct reasons with precision. This tempted inaccurate answers, such as the ‘she had just won ten gold coins’, which was explicitly rejected. This was a real test for some children, who may have struggled to navigate the text, comprehend it, and ignore what wasn’t relevant to answer the question. When planning reading lessons, create authentic, open-ended questions which elicit many different responses so that children get used to exploring texts in this way, drawing together ideas from across paragraphs to answer bigger questions. Ensure that follow-up questions dig a little deeper and probe children’s understanding, to help them identify nuances in what does or does not answer the question at hand.

We know that skilled readers monitor their own understanding. In a dense passage like this, that might mean noticing shifts between Merry’s actions, her emotions and the crowd’s reactions. The reader will likely need to ask themselves questions: ‘What’s happening here? What does this tell me? How do things look for Merry at this point?’ They’ll need to be identifying and summarising the key events within the extract - Merry’s fear of the bow breaking, her relief as the arrows found their mark, and her victory. When summarising, you might support children to summarise the main ideas in a paragraph to a single sentence, or the plot in just a few lines. You might use metacognitive talk to model how you ask yourself questions about the text’s meaning, e.g. ‘I’m wondering why…’ or ‘Is the author trying to tell me that…’ These different comprehension strategies can help children connect ideas and track meaning across the text. In reading lessons, incorporate teaching these strategies within rich text discussion. Demonstrate how these can be combined to make a mental model of the text and get to that ultimate goal of reading: comprehension and inference.

Words in context

Vocabulary is of course integral to understanding what we read, and there were certainly words which posed a level of challenge across the paper.

- A Life-Changing Game: children had to interpret words such as ‘anticipation’ and ‘intriguing’. This may have been a stumbling block for some.

- In the Cave: technical words such as ‘horizontal’ and ‘panel’ drew on subject and world knowledge.

- Longbow Girl: specialist archery terms sat alongside figurative expressions such as the ‘first flush of euphoria.’

Without wide reading experience and vocabulary instruction, this can quickly become a barrier. That’s why it’s so important to introduce children to a range of high-quality texts and explicitly teach new vocabulary. Pre-teaching vocabulary can be powerful, but children should also practise reading and unpicking the meaning of words in context. We can model strategies such as drawing on the clues around the unfamiliar word as, often, it’s the surrounding words that provide the extra hints needed to unlock meaning. Morphology is also key to unlocking word meanings, so model identifying root words and applying meaning of affixes to help with understanding and engage pupils in doing the same. If vocabulary teaching is on your radar, you may find this blog useful: Improving vocabulary for primary pupils.

Final thoughts

Overall, the 2025 Reading SATs paper was well-structured and fair. It rewarded reflective readers who could combine retrieval, inference, vocabulary knowledge, and give precise answers. To prepare children for reading with this pitch of challenge, both in SATs and – more importantly - wider reading experiences, we need to embed a broad, rich reading curriculum. Children should experience a wide range of genres, have the opportunity to read these with fluency and have meaningful discussions about them where they encouraged to dig a little deeper. Also, we must equip children with strategies to monitor their understanding, select evidence carefully, and tackle new vocabulary.

Come along to our Growing greater depth reading in year 5 and 6 or HFL Education Reading Fluency Showcase 2025 to further explore effective teaching of reading at UKS2.