Using a repertoire of simple drama techniques in the classroom can be a highly effective way of developing children’s literacy. Drama enables oral rehearsal of sentence structures and new vocabulary. It can develop reading fluency and comprehension, as well as idea generation for writing and key oracy skills for public speaking and performance.

A powerful cross-curricular tool, drama can also enrich subjects such as history and PSHE by inviting children to ‘step into the shoes’ of characters to explore key issues or events. When implemented well, drama injects energy and active learning into lessons, boosting pupil engagement and motivation. Whilst drama techniques can be used to develop spoken language, reading and writing, they can also be considered outcomes in their own right: as an effective performance for an audience.

It is worth noting that drama is a statutory golden thread running through the English curriculum, from role play and storytelling in the Early Years framework to the provision for drama emphasised in the English programmes of study: key stages 1 and 2.

The EYFS statutory framework - ELG Comprehension, states that children should:

‘Demonstrate understanding of what has been read to them by retelling stories

and narratives using their own words and recently introduced vocabulary.’

and ‘Use and understand recently introduced vocabulary… during role-play.’

The English programme of study tells us:

‘All pupils should be enabled to participate in and gain knowledge, skills and understanding associated with the artistic practice of drama. Pupils should be able to adopt, create and sustain a range of roles, responding appropriately to others in role. They should have opportunities to improvise, devise and script drama for one another and a range of audiences, as well as to rehearse, refine, share and respond thoughtfully to drama and theatre performances.’

Using drama can sometimes seem daunting, with concerns around behaviour management or ensuring high-quality outcomes. To make drama effective in lessons, scaffolding, modelling, and feedback are essential, along with high expectations.

In this blog, we will explore five drama techniques with a strong evidence base1 for impact on literacy development and provide practical tips on how to implement them effectively.

Readers’ Theatre

Readers’ Theatre has a significant impact on children’s reading fluency and comprehension. It is particularly effective in engaging reluctant readers and building their confidence. The approach involves a teacher modelling expressive reading, followed by repeated reading rehearsals, culminating in a performance of the text. This final step is crucial because of its motivational impact: it provides an authentic reason to re-read texts, a cornerstone of fluency development, and encourages expressive interpretation.

The performance should use minimal props or gestures. Instead, the focus should be on creating drama through the power of the spoken word. In a supportive classroom environment, with ample rehearsal, modelling, and feedback, Readers’ Theatre also strengthens oracy skills, such as making eye contact with the audience, and speaking with an expressive voice at an appropriate volume and pace.

The process of Readers’ Theatre also develops reading comprehension. As children explore how to read the text with expression, they begin to interpret the text, deciding which words or phrases to emphasise and why. In our experience, through repeated, active exposure, children also expand their vocabulary and familiarity with a variety of sentence structures and genres, all of which can in turn support writing.

To implement this drama technique successfully, embed a clear teaching sequence into regular practice. First, choose a short, engaging text that is at, or slightly above, age related expectations. Speeches, playscripts and poetry all lend themselves well to Readers’ Theatre. However, engaging sections of non-fiction and narrative are equally effective. As a rough guide, choose a section that would last about a minute. For longer pieces, give a section to different groups, so that when it comes to performance, the whole text is read.

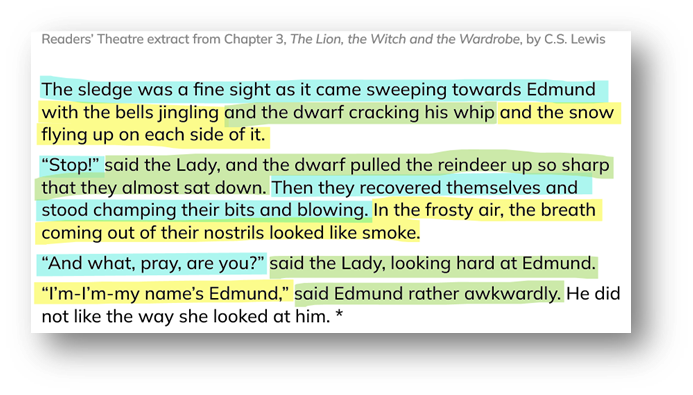

Highlight phrases or sentences in different colours to assign parts to groups (three is a good number). This supports prosody by prompting phrasing and moments of choral reading. It enables adaptations to be made, ensuring readers are given an appropriate level of challenge. Here is an example of what this could look like, from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, by C.S. Lewis:

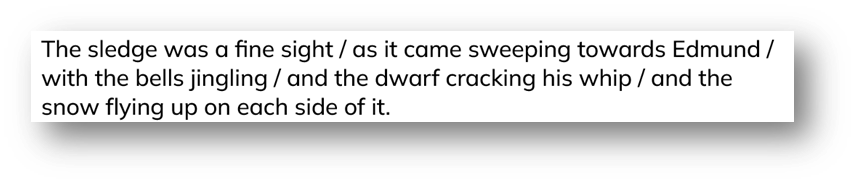

The teaching sequence follows the gradual release model of ‘I do – we do – you do’. Teaching begins with the teacher modelling an expressive read of the text. Then, the teacher ‘echo reads’ a short section. This involves reading the text in short phrases. The children echo back each phrase of the teacher’s expressive read as a chorus, mimicking their expression and volume:

This is where a bit of overacting from the teacher can be helpful, alongside high expectations for the children’s echo. The activity should be pacey, engaging, and responsive, involving repeated re-reading of phrases that children may find challenging or where their echo doesn’t effectively mimic the teacher’s expressiveness. The section is then re-read in longer sections, such as sentences, to build fluency. Lastly, children are invited to read the text in pairs or groups, using the prosody (expression, phrasing and intonation) that was modelled. During rehearsals, the teacher roams and supports, providing feedback and further modelling.

Only when fluency is secure should performance begin. Ensure children understand how to engage the audience by facing forward, looking up from scripts at points, and reading at the right pace and volume. Set expectations for audience behaviour and involve children in giving constructive feedback on fluency and expression. Maintain high expectations and if needed, ask groups to perform again after feedback.

Readers’ Theatre transforms reading lessons into engaging, purposeful experiences and can have a significant impact on reading attainment.

Freeze frames

Freeze Framing is a drama technique which allows children to explore a particular scene from a text in greater depth by physically recreating it and then ‘freezing’ in role - like pressing the ‘pause’ button on a moment in the story. Begin by reading a short, significant extract from the text, such as Edmund’s first encounter with the White Witch in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Model how to identify clues in the text to visualise the characters and setting. Then, demonstrate how to use these clues to sculpt a scene using volunteers, explaining how body language, facial expressions, and positioning can convey character and emotion.

Warm up activities can help if your class is new to this technique or feeling self-conscious. Emotion Statues involves the teacher calling out emotions (e.g. joy, fear, anger) and children freezing in a pose that expresses that emotion. Encourage facial expressions and body posture and ask children to exaggerate these, to comic effect. Character Sculpting is another useful warm up where one pupil acts as a ‘sculptor’ and gently positions a partner into the form of a character. The sculptor explains their choices as they work. This helps to build understanding of how physical choices convey meaning.

Next, give groups time to discuss how they will represent the chosen moment, encouraging them to use textual evidence to inform their choices, such as ‘The Lady frowned…looking sterner than ever’, to create a living statue of the witch. As they create their freeze frames, prompt them to consider levels (e.g. standing, sitting, kneeling), spatial relationships and expressive detail. Invite each group to perform their freeze frame, using a countdown to signal when to freeze. Facilitate discussion by asking questions about the characters’ thoughts, feelings and motivations, and exploring the reasons behind their physical choices. This can help develop children’s understanding of the ‘show don’t tell’ technique in writing. Descriptive phrases linked to the freeze frames, such as slumped shoulders for sadness, or clenched fists for anger could be recorded for use when writing.

With effective modelling and high expectations, children will use retrieval skills to gather information about the witch’s appearance and make inferences about Edmund’s internal conflict and the witch’s hidden intentions. Photographs of the freeze frames can be used as a stimulus for writing activities, such as diary entries from a character’s point of view.

Freeze frames can also be used to summarise a section of narrative by asking children to create a sequence of frames. This is sometimes called a Living Timeline. The audience can be asked to close their eyes while the group quickly rearranges into the next frame, then open them to view the new moment. Alternatively, half the class could present a series of freeze frames to the other half. This can be accompanied by narration or discussion about what has been included or omitted. You might also extend this by asking children to create a freeze frame that predicts what could happen next.

To develop this approach further, introduce Thought Tracking. This technique involves tapping each performer on the shoulder while in freeze frame, prompting them to voice their character’s inner thoughts. For instance, Edmund might whisper, “If I help her, maybe I’ll be more important than Lucy,” while the witch might say gleefully, “He wants to feel important - I’ll give him just enough to keep him loyal.” Support idea generation by modelling high-quality examples and giving children time to rehearse in groups. You can even extend thought tracking to the setting itself: what might the trees of Narnia be thinking as they witness this scene? This can lead to a deeper understanding of how writers use personification to create mood and atmosphere.

Freeze frames can also be developed into a soundscape, where the teacher acts as a conductor and groups contribute sounds from the scene, such as the cold wind blowing or the sound of the sleigh. This helps children understand how writers use the senses to enrich their writing.

Combined with Thought Tracking and a soundscape, a freeze frame can become an atmospheric performance.

This technique is very versatile and can be used in a range of contexts. It is also controlled and structured, which helps to avoid behavioural issues. When used consistently, freeze frames become a quick and powerful tool that fits easily into lessons.

Hot Seating

Hot Seating is a drama technique where someone takes on the role of a character from a story, play or historical event and is questioned by their peers while remaining in character. This encourages children to think deeply about motivation, feelings and perspective, requiring them to draw on inference and empathy. Effective modelling is key, along with scaffolding such as speaking frames, to support children in formulating questions and answers.

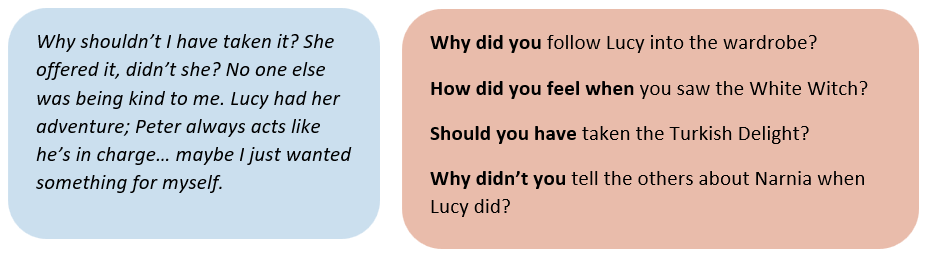

Continuing with our example from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, a teacher might model Hot Seating by taking on the role of Edmund and responding to questions from the class. A speaking frame can be provided for pairs or small groups, to scaffold both questioning and responses in role. For example:

As an adaptation, you could offer a faded scaffold, where only the sentence stems are provided (in bold above), allowing children to devise their own questions. This supports the development of a key comprehension strategy: questioning the text. Hot Seating is an opportunity for children to orally rehearse vocabulary and features that would be useful in their writing. Before Hot Seating, a bank of ideas could be created with the class to suggest ways to physically describe inner thoughts and feelings. Ambitious vocabulary from the text could be highlighted for use, such as ‘proud and cold and stern’ from our example text to describe the witch.

Hot Seating works well alongside Role on the Wall, a strategy that involves drawing an outline of a character (often on a large sheet of paper) and annotating it with information. Inside the outline, children write the character’s inner thoughts and feelings. Outside the outline, they record what others say or think about the character or observable facts such as appearance and actions. This supports Hot Seating by helping children gather ideas about the character beforehand and can help capture the learning for future writing about the text. Insights that are discovered through the drama activity can be added to the outline afterwards, prompting discussion about what has been learned - for example, Edmund’s jealousy, desire for recognition and confusion about the witch’sintentions.

Role on the Wall also provides a foundation for writing in role, such as journalling from the character’s point of view or composing a letter. These activities deepen comprehension and offer valuable opportunities for assessment for learning.

Conscience alley

Conscience Alley is a drama strategy used to explore a character’s decision-making process, usually exploring a moment of dilemma. The class forms two lines facing each other, creating a ‘path’ or ‘alley’ down the middle. One pupil (or the teacher) walks slowly down the alley in role as a character who is facing a dilemma. As they walk, children on either side speak aloud persuasive thoughts, advice, or arguments - some encouraging one choice, others suggesting the opposite. Sometimes, two conscience alleys can work well, so one half of the class can watch the other.

This technique encourages children to actively engage with key moments in a narrative by exploring different viewpoints and internal conflicts. It helps develop empathy and strengthens inference skills, allowing children to connect more deeply with characters and engage actively with key moments in a narrative.

To return to our example text as an example: Edmund’s Dilemma. In this scene, Edmund has just encountered the White Witch, who tempts him with Turkish Delight and the promise of becoming a prince, on the condition that he brings his siblings to her. This moment marks a turning point in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, filled with internal conflict and moral tension.

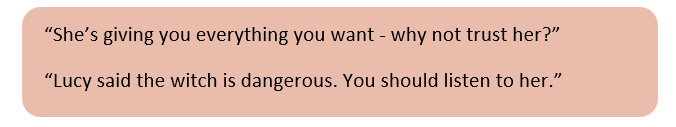

To explore this, begin by establishing two sides to the dilemma: should he bring his siblings to the witch or tell them what happened? Collect ideas for each side, including any vocabulary or features you would like them to orally rehearse, to establish high expectations. Model how to whisper expressively ideas from each side. Give children time to rehearse ideas. Using mini whiteboards to draft their sentences can help children retain ideas and use more ambitious language. Choose one volunteer to take on the role of Edmund and ask them to walk slowly down an ‘alley’ formed by the rest of the class. As he passes, children on either side speak aloud lines that represent his inner thoughts or external influences. These voices reflect the conflicting emotions and pressures Edmund faces. Possible lines include:

Once Edmund reaches the end of the alley, pause the action and invite reflection. Ask children:

This activity is a powerful and engaging way to invite children to connect their own opinions and values to the text. Along with developing children’s understanding of the text, Conscience Alley also supports children’s understanding as writers of how character dilemma is part of narrative structure and provides opportunities for children to practise persuasive language.

Improvising a scene

Improvisation works best in the classroom when it is brief and clearly structured. Children need to understand what their character wants in the scene, as this drives their dialogue and gives the improvisation direction. Techniques such as Freeze Frames and Hot Seating help children explore how different characters might act, move and speak - skills that can be applied to the more complex task of improvising a scene.

To begin, children could re-enact a short section of dialogue from the text. Work with them to identify clues the author uses to convey character, as can be seen below in bold in our example text:

“And what, pray, are you?” said the Lady, looking hard at Edmund.

“I’m-I’m-my name’s Edmund,” said Edmund rather awkwardly. He did not like the way she looked at him.

The Lady frowned, “Is that how you address a Queen?” she asked, looking sterner than ever.

Linking close reading like this to a performance makes it purposeful and invites children to interpret what they have read. This builds on Readers’ Theatre by encouraging children to embody characters and physically act out scenes.

You can extend the activity by inviting children to create alternative scenes. For example: What if Edmund refused the Turkish Delight? Or, in small groups, children could create a scene where Lucy suspects Edmund is hiding something and tries to persuade him to tell the truth. From improvisation, they could collaboratively write a script or a narrative scene with dialogue (writing threes work well for this, with children taking turns to write each sentence).

This activity supports a range of literacy skills. Children practise persuasive language and emotional expression through speaking and listening, while also developing their use of dialogue by turning their role-play into a play script or narrative passage. It encourages inference and empathy as children explore character relationships and moral dilemmas.

Modelling is key. Provide scaffolds, such as adapted dialogue from the text, and establish high expectations with clear success criteria for speaking, listening and performance. After modelling, roam and support groups. Set time limits and use mini plenaries to reinforce success criteria. Maintain clear routines, like cueing groups with ‘Lights, camera, action!’, and offer feedback through audience responses such as ‘two stars and a wish.’ Invite groups to refine and redo performances where needed.

Why use drama in the classroom?

These drama techniques, in combination with Readers’ Theatre, can transform lessons into active and engaging learning experiences. They can deepen comprehension and facilitate thoughtful discussions. Through drama, children practise the key comprehension strategies of predicting, visualising, questioning, summarising and making inferences. Less skilled readers may not yet have experienced the enjoyment that comes from inferring meaning or visualising scenes while reading. Drama techniques can help bring texts to life. This not only supports comprehension but also nurtures a love of reading, helping children connect emotionally with stories and develop reading for pleasure as a lifelong habit. Drama can also develop children as writers, enabling them to rehearse ideas and language that underpin writing.

Despite its many benefits, and its deep roots in our literary heritage and creative industries, drama in schools is in decline. The Fabian Society (2019) reported that 68% of primary teachers in England believe there is less arts education now than in 2010, and 49% say the quality has declined. The Drama and Theatre Education Alliance (DTEA) similarly found that ‘Drama in schools is in steep decline,’ with long-term reductions in provision, particularly across key stages 1–3. Access to the arts is increasingly limited, especially for children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

By embedding drama techniques into everyday classroom practice, teachers not only enhance children’s literacy skills but also open the door to a rich art form that promotes self-expression and confidence. To further develop drama in schools, the DTEA advocates that, ‘Every young person should have at least one theatre experience a year - seeing a show, participating in workshops, performing, and engaging in the creative process.’ As teachers and children grow in confidence with using drama across the curriculum, the quality and ambition of school performances will naturally rise, from Nativity plays to class assemblies and Year 6 leavers’ shows. By championing drama in the classroom, we not only enrich literacy and school’s cultural life, but also empower children to find their confidence, and their voice.

We would love to hear from you about your successes or challenges with implementing drama in your school – do get in touch via the email below.

If you are interested in finding out more about drama in the classroom, please see the references and links below.

References:

- Research-Art-Works-OSU.pdf; The Impact of Drama Classes on Literacy and Writing Skills - Theatretrain ; Using Drama and Theater in the Classroom to Promote Literacy - Novak Djokovic Foundation

- Primary colours | Fabian Society

- Drama in Schools | Primary Drama | Key Stage 3 Drama | Drama and Theatre Education Alliance (DTEA)

Readers’ Theatre:

The role of the teacher in reader’s theatre instruction Timothy Rasinski

Drama resources and CPD:

Teacher resources | National Theatre

RSC Learning | Primary Play Days | Royal Shakespeare Company