This is the first in a series of blogs about The writing framework, published by the Department for Education in July 2025, and its implications for classroom practice. If you have time and the inclination, we do recommend reading the framework in its entirety. However, our aim is to help translate this hefty 150-page document into easy-to-follow advice and guidance for busy classroom teachers, subject and school leaders.

As can be seen in the Acknowledgements (p.11), they consulted widely, which is commendable. However, this has at times resulted in a mix of messages, as differing views on writing jostle to be heard within the document.

In this series of blogs, we will explore the real strengths of The writing framework, while also addressing some of its ‘blind spots’ to help ensure that misinterpretation of its guidance does not lead to unintended consequences in the classroom.

Whilst the document is non-statutory and will be updated after a revised national curriculum is drafted, it is worth noting that the framework’s introduction asserts:

‘This document’s key objective is to help schools meet the expectations set out in the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) statutory framework and the National Curriculum. It aligns with Ofsted’s education inspection framework and with The reading framework.’

The framework is divided into eight sections:

Section 1: The importance of writing and a conceptual model

Section 2: The importance of reception

Section 3: Transcription – handwriting and spelling

Section 4: Composition

Section 5: Pupils who need the most support

Section 6: Writing across the curriculum

Section 7: Leadership and management of writing

Section 8: National assessments

For this blog, we will focus on Section 1: The importance of writing and a conceptual model. Other sections will be explored in later blogs.

What is writing and why does it matter?

Section 1 contains some powerful and inspiring messages about writing that encourage us to reflect on the extent to which our current classroom practice enables children to experience what writing can be:

‘Writing is ... key to social experiences as it enables participation in social communication […] writing is a highly creative process, allowing people to create imaginary worlds, entertain others and paint with words. Writing can also be a form of self-expression: it offers young people an opportunity to reflect upon themselves, their interests and their worlds…’ p. 13

It describes how writing, as a creative act of self-expression, can contribute to the well-being of the writer and the intended audience. So, the framework begins with asserting the vital importance of children writing for authentic audiences and purposes, and for children to have choice over what they write.

Section 1 also emphasises how writing develops children’s thinking and learning:

‘It helps pupils to consider information more deeply than when they are simply reading it; it enhances the learning of subject matter and helps cement that learning in long-term memory.’ p13

It goes on to note that ‘when writers abdicate composition to artificial intelligence (AI), none of these cognitive advantages applies.’ Writing to think and reflect, then, has a key part to play in learning across the curriculum, which is developed further in Section 6 and we will explore in more depth in a later blog.

Another strength in this first section is its emphasis on the importance of spoken language in writing development: interactions with adults, exposure to stories and back-and-forth talk. Crucially, it notes the need to teach children how to engage in dialogue to generate ideas for writing, with clear structures and talk routines modelled by teachers.

Managing cognitive load and the demands on the working memory of young writers is a key theme. The framework asserts the need to slow writing down:

‘Writing should not be rushed: pupils should concentrate on the quality of their writing rather than producing large amounts of lower-quality text.’ p19

This encourages us to reflect on how we structure and sequence writing lessons. Are we giving children enough time and support to generate ideas and plan? Are we modelling writing features in manageable steps, or overwhelming them with too many at once? Do we use mini-plenaries, for example, to reinforce success criteria and share good examples? And are we building in time for editing and proofreading?

Echoing messages from Telling the story: the English education subject report (DfE, 2024) and Strong foundations in the first years of school (DfE, 2024) reports, the framework stresses the importance of securing foundational writing skills before moving on to more complex writing, particularly handwriting and spelling. Poor spelling and handwriting can impact young writers’ self-esteem and act as barriers to writing. As it notes, ‘fluency in transcription frees up working memory to focus on composing writing.’ To remove transcriptional barriers to writing, we need to ensure handwriting and spelling are being taught regularly, and that misconceptions and gaps in learning are addressed, such as securing letter formation before joining. Importantly, though, it also emphasises that grammar and spelling should link to purposeful writing:

‘Others may be turned off writing, if teaching is focused too heavily on learning lists of spellings and grammatical concepts, out of context and with little understanding of their potential for expressive impact.’ p21

It stresses that:

‘just as decoding is not reading, transcription is not writing: it is essential but not sufficient.’ p21

Here the framework is reminding us that development of transcriptional fluency is important so children can focus on composition, on the creative act itself. However, as we focus on children’s handwriting, spelling and grammar, are we linking them to the purpose: to communicate effectively to the reader, to have an ‘expressive impact’?

Motivation is highlighted as a crucial driver of children’s success in writing. The framework explores different kinds of motivation linked to writing, explaining how one form of motivation is derived from feelings of success. This is why slowing down the writing process is so important: it helps ensure a high success rate for all children by teaching in small steps and addressing misconceptions. This might mean revisiting earlier learning, such as securing accurate sentence demarcation, before introducing more complex sentence structures. Conversely, if we rush the writing process, young writers can become overwhelmed and frustrated.

Another form of motivation is highlighted: giving children choice in what they want to write about and who they want to write for. It asserts:

‘Too often, pupils ‘learn to write for the circular purpose of learning to write’ and find little personal purpose or value in it.’ p22

The framework encourages us to think about the writing tasks we give children: what’s in it for them? Do they get to write about what interests them, as the framework suggests? For example, writing about ‘granny’s cooking’ is listed as a legitimate and interesting to topic to write about at school. In addition to the teacher and their classmates as readers, can we find authentic writing tasks where children’s writing has a real purpose and audience, perhaps publishing their work in the school library, or sharing with another class, or even beyond the school gates? Could children share their writing with their family at home or even with the local community, for example? In the context of plummeting attitudes towards writing amongst young people, especially among primary-aged pupils, as shown by the National Literacy Trust’s research, motivation should be at the forefront of our minds.

Blind spots and unintended consequences

While the framework presents many strengths in this section, it also introduces a conceptual view of writing that may carry unintended consequences. This perspective could potentially have a detrimental impact on how writing is taught in practice.

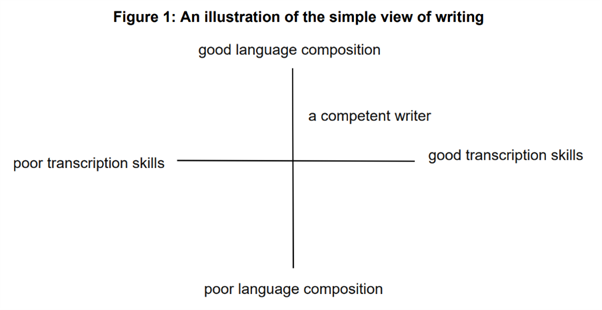

The Simple View of Writing (Berninger et al, 2002) is suggested as a way to think about writing, which boils writing down to: transcription + composition = competent writer:

The risk with the Simple View of Writing is that it reduces writing to a formula: master transcription, then add composition. This suggests a linear process that doesn’t reflect the complexity of real writing. What exactly is meant by ‘composition’? It involves generating ideas, experimenting with language, and writing with purpose and audience in mind. If we treat transcription as a prerequisite, we may end up prioritising spelling and handwriting over creativity and meaning, like teaching children scales but never letting them play music.

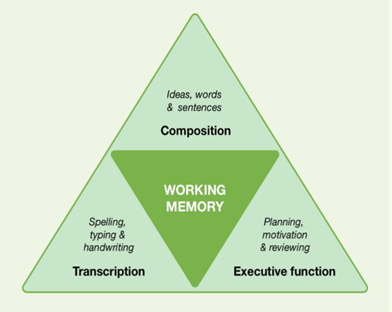

Interestingly, this model has since been revised to the ‘Not So Simple View of Writing’ (Adapted by EEF from: Berninger et al.,2002), which better acknowledges the role of motivation and the complexity of composition:

The need to manage the demands we make on working memory in writing lessons is central in this model, affirming the need to teach the writing process in small steps, avoid overloading writing tasks with too many writing features, and develop children’s transcriptional fluency. However, this model still overlooks the importance of helping children develop their identities as writers. This is likely to be through tasks that encourage self-expression, offer choice, and involve real audiences and purposes from the earliest stages, while also developing transcription skills like handwriting, spelling, and sentence construction. We need to ask ourselves not just what the writing needs, but also what our young writers need.

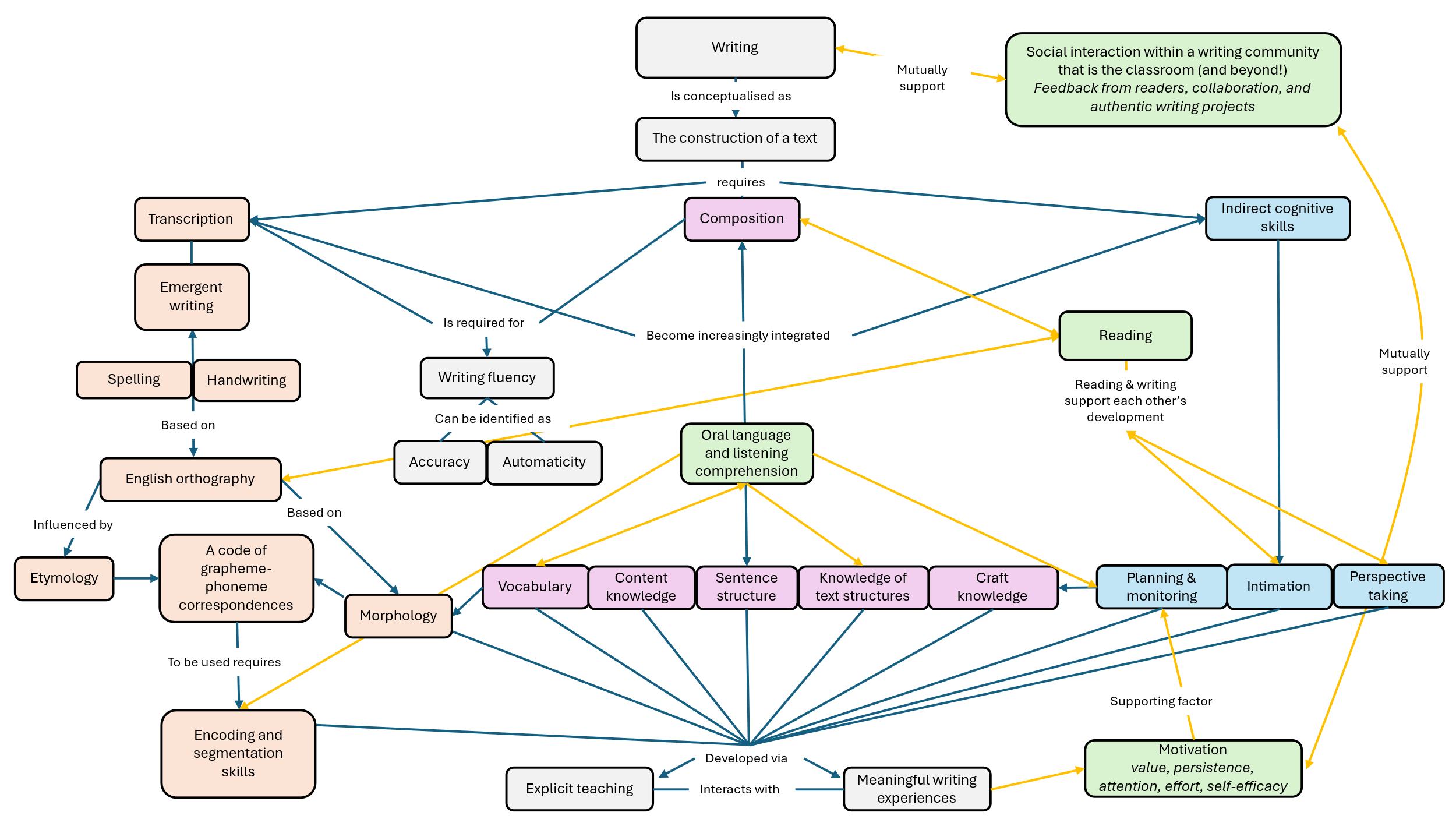

The framework could have chosen a conceptual model for writing which attempts to celebrate the complexity and richness of the writing process and help teachers develop a pedagogy which address this, such as The Writing for Pleasure Centre’s ‘The Writing Map’:

Note how in this model, writing is underpinned by meaningful writing experiences and explicit teaching, supported by motivation and social communication, alongside transcriptional skills. As teachers, we need to embrace the complexity of the writing process and develop a culture of a writing community in our classrooms.

At HFL, our writing curriculum, ESSENTIALWRITING, places audience and purpose at the heart of writing projects. At the earliest stages of writing in the Early Years, children are invited to apply their transcriptional skills in the context of making books on topics of their choice. As children develop their writing, our English plans weave in grammar progression by noticing what writers use in mentor texts and explicitly modelling how to use them in the context of our own writing to have an impact on the reader.

Any framework for teaching writing needs to help teachers without oversimplifying what writing really is. The Simple View of Writing may seem helpful at first, but it risks turning writing into a step-by-step formula (first transcription, then composition) when, in reality, writing is much more complex. If we want children to enjoy writing and see themselves as writers, we need to give them real reasons to write, choices in what they write, and opportunities to express themselves.

ESSENTIALWRITING | HFL Education

How to help with handwriting | HFL Education

An introduction to ESSENTIALspelling | HFL Education

Young, R., & Ferguson, F. (2025). The Writing Map. The Writing for Pleasure Centre The Writing Map & Evidence-Informed Writing Teaching

Berninger, V. W., Vaughan, K., Abbott, R. D., Begay, K. K., Coleman, K. B., Curtin, G., Hawkins, J. M., and Graham, S. (2002). ‘Teaching spelling and composition alone and together: Implications for the simple view of writing’ Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), pp. 291–304

Join us at our upcoming English Conference Writing Matters: Bridging Research and Policy into Primary Classroom Practice to explore the key themes within the writing framework and hear from its lead author, Dr Tim Mills, alongside other expert speakers including Professor Steve Graham, Professor Teresa Cremin and the wonderful author Bethan Woollvin.