With the growing popularity of whole class guided reading in key stage 2 classrooms, where all children in the class are reading the same text guided by the teacher, we felt it timely to reflect on the strengths of this process but also consider how to avoid the potential pitfalls that can result from moving to this model of reading teaching. Here we attempt to address those unintended consequences. We will consider what teachers can do to ensure that all children have the best possible experience and to develop their pupils’ love of reading alongside their journey to becoming proficient readers.

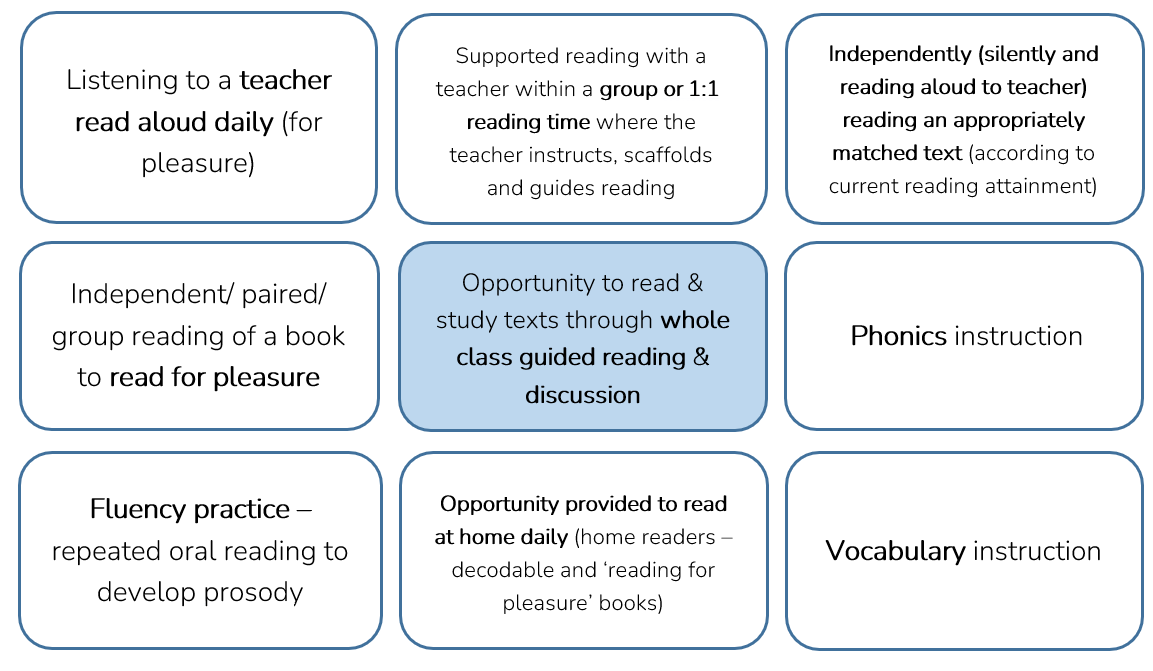

How whole class guided reading fits into a ‘reading diet’:

First, let’s address the idea of the reading diet of each child within a class. Whole class guided reading should ideally feature as one piece of the puzzle within a wider reading diet that a school offers. Here are some examples of what these reading opportunities (provided throughout the week) could be:

Of course, the above list is not exhaustive - particularly regarding some of the wider reading for pleasure practices that are so important within every classroom. Some of these elements are inter-connected. For example, children will learn more vocabulary during many of the shared and guided reading sessions, but vocabulary instruction also needs to be built into explicit teaching time, which will lead to deeper comprehension during independent and guided reading. Shanahan discusses academic learning time (ALT) in an enlightening recent blog and how this definition differs to allotted time on the timetable. For example, there may be 45 minutes of whole class guided reading allocated on the daily timetable, but if a child is not reading and simply page-turning during this time, the lesson does not translate into 45 minutes of academic learning time for that child. Some children will need to read more and have a greater reading diet (essentially, more time to practise reading!) during their school day compared to other children in the class. Consider struggling or less confident readers within the class (often referred to by Ofsted as working within the lowest 20th percentile of reading attainment) - these children will need more of a teacher’s teaching time and support, as well as more time and/ or interventions dedicated to different areas of reading instruction (this could be phonics instruction, fluency strategies, etc., according to the needs of each child). This is additional instruction, not replacement instruction. In this way, we are ensuring equity of access into reading proficiency and there is arguably no greater responsibility placed on schools than ensuring that all children are proficient readers by the time they leave their primary education.

Guided reading – points for consideration

When it comes to children’s reading diets, some key questions to ask would be:

- do all children have the time to practise and improve their reading through reading aloud, paired reading and discussion, as well as exploring a text independently within the school day?

- are there opportunities for children to repeatedly re-read texts, to practise fluency and use of prosody when reading?

- are reading for pleasure practices embedded into daily classroom routines to foster a love of reading?

- are children listened to whilst reading aloud in a supportive, 1:1 discussion with the teacher which moves their reading on (rather than in front of the whole class)?

- and, coming back to Shanahan’s point, what is preventing allotted time for reading on the timetable becoming academic learning time, especially for the children who might need this the most?

Whole class guided reading brings with it the benefit of all children embarking on the same reading journey of the same text, providing a shared experience and developing a community of readers. There is also evidence that reading challenging, complex novels aloud and at a fast pace daily resulted in lower-attaining readers making 18 months progress in 12 weeks (Literacy, vol. 53, issue 2, May 2019). All children can learn something worthwhile from being taught using a high-quality, challenging text. However, in some cases, children are removed from the whole class guided reading lesson for a separate reading intervention. If that’s the case, it might be worth asking - is it really ‘whole class’? The removal of some children surely undermines the purpose of moving to this model in the first place. Consider the impact upon self-esteem and a sense of belonging for these young readers, and how we can ensure that these children are given more opportunities to read and practise reading than anyone else and, if necessary, provided with interventions in addition to the usual reading diet. So, if we want to include all children, let’s turn our attention to thinking about ways in which all pupils can participate within the whole class guided reading lesson.

Ensuring access for all children during whole class guided reading:

An admirable reason for many schools moving towards whole class guided reading is to ensure that all children have access to rich and diverse literature that is pitched at age-appropriate interests and expectations. A potential pitfall of this can mean that children who are not reading at the expected standard within the class will struggle to read the selected text (ideally, only <10% of words encountered should be unknown/unfamiliar in guided reading texts). They might well be able to follow when the book or text is being read to them, but they are not necessarily practising the skills of decoding and developing the automaticity that they need from their reading teaching because too many words are unknown or not yet decodable. A child may be following the text by listening to it, but language comprehension (an understanding of written text) is not the same as listening comprehension (Such, 2021 p. 52). As a result, teachers will often (and rightly so) avoid asking this child to read aloud and be placed under scrutiny in front of the class, but this also means that the opportunity to ‘tune into’ this child reading and teach specific reading strategies, is lost. Thinking back to the reading diet, as long as the teacher has had ample occasions (hopefully twice a week, ideally more) to listen to more vulnerable readers read appropriately levelled texts during 1:1 sessions - and used other occasions to teach specific reading strategies that the child needs to make accelerated progress - we should consider ways to ensure their involvement during whole class reading teaching as well.

Guided reading: Strategies for active participation for all

The third part of this blog will provide advice about the types of discussion, questioning and other activities that could take place within the whole class guided reading lesson. For now, let’s turn our attention to the preparation for the lesson and how to ensure access for all into the text via these strategies:

- Pre-teaching vocabulary – identify any new or difficult vocabulary from the text which is going to be read and discussed during the whole class guided reading lesson. Discuss and teach these words before the lesson (this could be with the whole class as this will benefit all pupils, as well as any vulnerable readers), looking at etymology and using the word within sentences orally or in writing. Supply visual cues to support understanding of unknown or tricky vocabulary for children to refer back to during whole class guided reading lessons and ask children to spot the words that they have been taught within the text, becoming ‘word detectives’ and discussing how those same words have been used by the author.

- Pre-teaching context or background knowledge - in Reading Reconsidered, Lemov discusses the vital importance of context or background knowledge to reading comprehension. Lemov argues that a reading curriculum should embed secondary non-fiction texts in combination with a primary text, in order to increase pupils’ background knowledge of the primary text and therefore develop comprehension. For example, let’s imagine that a class is studying the wonderful The Girl Who Stole an Elephant by Nizrana Farook. Consider what children may not know in terms of the background knowledge needed to fully access this text: Do they need to know more about Sri Lankan geography and culture? The biodiversity of jungle life? The nuances of the behaviour and communication of elephants? It may be necessary to adapt, combine and amend non-fiction texts and provide these for children to enhance their understanding of the whole class guided reading text. Again, this will benefit all pupils in the classroom.

- Using supportive or assisted reading within whole class guided reading lessons – in the excellent Megabook of Fluency, Tim Rasinski & Melanie Cheesman-Smith discuss the importance of pupils reading chorally as part of a group or reading with a more fluent partner such as a teacher, parent, teaching assistant, older pupil or even a classmate. Some research studies have found that dysfluent readers make accelerated progress when they read aloud whilst simultaneously hearing a more fluent reading of the same text.

- Build in opportunities for repeated reading during whole class guided reading lessons. As well as wider reading, deeper reading is essential for children to repeatedly read the same text several times until they achieve some degree of automaticity (they are not struggling to decode the words). Each time, pupils will show improved reading with each successive reading (Rasinski, 2012). This strategy is widely employed on the HFL Reading Fluency Project.

- Explicitly teach reading habits – it can often be the case that children will lose their place in the text if they are trying to keep up with the pace of the text being read aloud whilst following along with reading the written text simultaneously. Make sure that there are regular reminders for children to track along with their finger or use a ruler/ piece of paper to follow the line that is being read. Some children may also need to draw what they understand from the text – this will support their visualisation. Whatever method that helps each child to access their reading material will only be a good thing!

- Use a visualiser! The effective use of a decent visualiser can be the best teaching tool within any classroom. Modelling how to follow the text as it is being read (teaching reading habits, as above), annotating passages, text marking to denote phrases for effective prosody, highlighting, underlining or circling words – all of these strategies can be demonstrated to the class with the reading material placed under the visualiser. If a child loses their place whilst the text is being read aloud, knowing that they can simply look up at the screen to see the text and reorientate themselves – without asking or needing to be prompted by the teacher – is empowering. A good visualiser* is worth investing in. A game-changer, truly.

The suggestions that we are offering are not intended to require any radical change but to show that, sometimes, as Daniel Sobel and Sara Alston say, some children may need a quick and simple adjustment to a lesson, while others may need a part of it to be adapted. To conclude in their words: ‘In the end, it [inclusion] boils down to good routines and practices that do not take up much time but are rich in maximising children’s engagement and that sense of ‘I belong and can be successful in this class.’’ (Sobel & Alston, 2021: p. 28).

References:

- Doug Lemov et al (2016), Reading Reconsidered

- Tim Rasinski & Melissa Cheesman-Smith (2021), The Megabook of Fluency

- Tim Rasinski, ‘Why Reading Fluency should be hot’ - The Reading Teacher Vol. 65 Issue 8 (May 2012)

- Timothy Shanahan, ‘What’s the Role of Amount of Reading Instruction?’, 11th March 2023

- Daniel Sobel & Sara Alston (2021), The Inclusive Classroom: A New Approach to Differentiation

- Christopher Such (2021), The Art and Science of Primary Reading

*It can be difficult to find a good visualiser with so many on the market – it’s worth paying a little bit extra (around £100) for a decent one.