Do you ever hear someone speak about a topic of interest and spend the whole time nodding emphatically and inwardly screaming agreement? This was me at the start of the term, having listened to Dan Nicholls, Director of Education at Cabot Learning Federation, speaking about disadvantaged pupils in our schools. This is an issue close to my heart and is something I have always felt compelled to champion. It needs to go beyond inspirational words and quotes, and beyond images of 3 children trying to look over a wall to help explain equality vs equity.

My aim for this blog is to share key messages from Dan Nicholls, my own thoughts, and to provide some guidance about practical changes that can be made in schools to keep chipping away at the disadvantaged gap.

What do the government mean by ‘disadvantaged’?

Pupil eligibility definitions can be found in Pupil Premium 2022 to 2023: technical note

Schools must use Pupil Premium Grant (PPG) funding for the purpose of raising the educational attainment of Previously Looked After Children (PLAC), Looked After Children (LAC) and pupils who are eligible for FSM Ever 6.

In line with the 3-tiered approach in EEF’s pupil premium guide, activities must be those that:

- support the quality of teaching, such as staff professional development

- provide targeted academic support, such as tutoring; and

- tackle non-academic barriers to academic success, such as attendance, behaviour and social and emotional support

(Education & Skills Funding Agency, 2022)

It is important to note that there may be some children for whom the school still receive PPG, but who are not currently in receipt of Free School Meals (FSM). How can this be? Well, these are children who have experienced disadvantage at some point, but who economically are now above the threshold for FSM. The PPG continues to be provided for a further 6 years as it is known that economic hardship has lasting effects, well beyond the time in question. This group of pupils are often referred to within data as FSM6 or FSM Ever 6.

Accumulated disadvantage / advantage

Dan Nicholls used the phrase ‘accumulated disadvantage’ which was really powerful when considering the journey these children have had to date. This suggests that advantaged children generally have led a life thus far where their economic situation has meant that they are in a much more secure and stable position mentally and emotionally to be able to take advantage of opportunities as they arise, and that when they do experience a setback, they bounce back much more quickly. With each and every successful experience, their ‘advantage’ grows.

In comparison, a child who has experienced economic hardship at some point, may not have developed a deep sense of self, built up over years of making meaningful connections with others and so do not feel that this community, this education system, is for them. They are ‘done to’ rather than active participants in the experience. So, each and every unsuccessful experience fuels their need to withdraw to reduce possible future failure. They are conditioned to believe that they are safer if they do not actively engage.

The bottom line is that it’s not just about not being able to afford a computer!

How does this translate into mathematics?

Maths is a rich subject, full of connections and possibilities, which can feel overwhelming to a disadvantaged child, who may just be wanting to get the answer ‘right’. Problem solving and reasoning require an inquisitive mind, one that asks questions and interrogates the information provided in order to find a solution. The very nature of maths as a subject requires a great deal of resilience, which is what we know our disadvantaged pupils can lack. This is also why we, as subject leaders, often hear teachers say ‘child X just lacks confidence’ in maths. It is because these children have opted out from the very beginning, as a way of protecting themselves from failure. They simply are not advantaged enough to take risks. The real issue here is not the lack of confidence; it is limited experiences of success.

Why is this relevant?

This level of understanding about our most vulnerable pupils is crucial if we are to make a difference. Not just because Ofsted says so, or because our data shows that fewer FSM6 children make age related, but because it is our duty to try to make sure that every child reaches their potential and that we see them into the wider world with the skills and knowledge to enable success.

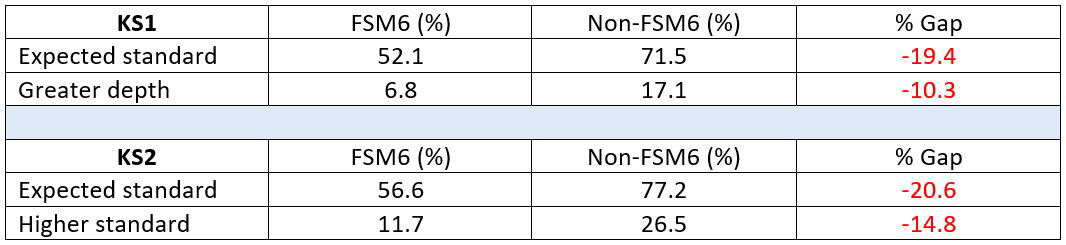

What does the data say?

National data shows that FSM6 pupils achieve below that of their non-FSM peers across the board, at every age and in every subject. Below shows the data for mathematics from 2022.

Note: this data is provisional at the time of publishing.

Is this a similar picture in your school?

So now let’s delve a little deeper. Where are these pupils?

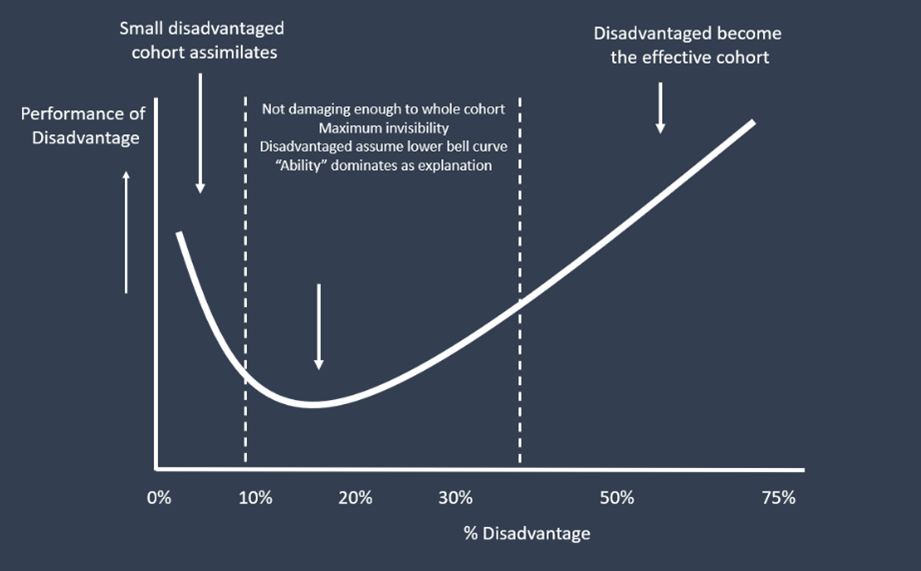

Data suggests that disadvantaged pupils generally do well in schools where there are either small proportions of disadvantaged pupils or large proportions (see image below), where disadvantaged become the majority, rather than minority. Those schools who have a significant, but not a particularly large or small, population of disadvantaged pupils are the ones who tend to not be as successful at closing the gap.

As a leader in your school, this is your first step: what does your data say?

- How many disadvantaged pupils do you have?

- Are there any year groups that have more or less than others?

- What are their start and exit points like?

- What is the progress of disadvantaged pupils in your school?

Don’t forget to look at both their attainment and progress in maths as well as combined (reading, writing and maths), as this can help you to pin-point where the need for improvement is.

How can we advantage the disadvantaged?

1. Identify the children

First from the data and then on an individual basis.

As a teacher, you should know these children. What do they like? Who are their friends? Who drops them off in the morning? These are all important things for the class teacher to know or else they have no chance at all in helping the child to feel like they belong.

2. Shift the language

How are these pupils referred to?

Dan Nicholls suggested the term ‘delayed attainment’ is helpful as it suggests potential. ‘Ability’ should be avoided as it gives the impression that their attainment is innate and pre-determined. ‘Those presently experiencing disadvantage’ is another phrase worth sharing with staff, as it separates the child’s economic status from who they are as a person. Shifting the language used to talk about this vulnerable group can lead to raised expectations and even alter the mindset of adults working in the school about what this group could achieve, if given the chance.

3. Disadvantaged FIRST and ALWAYS

When conducting pupil progress meetings, leaders should focus on the disadvantaged group first. By doing this, leadership sets the precedent that they are important. Similarly, teachers could mark their disadvantaged children’s books first to ensure the highest quality of feedback (before the tiredness sets in!!). Despite what some may argue, this is not at the expense of the non-FSM pupils. We are simply giving advantage to the disadvantaged in a bid to make it a more even playing field.

Timing is everything.

4. When is maths taught in the day?

If it is always taught first thing, and you know that some of your FSM children come to school hungry or tired, or even late, then always having maths first means that this time will never be as productive as in other subjects that come later in the timetable. Similarly, if you know that some of your children struggle to regulate emotions at breaktime, and maths is always straight after, they may be missing crucial learning time simply from needing time to resolve and restore. The key here is to know your pupils and adapt to suit their needs. It may also be that little and often will make the difference to the pupils’ retention. Just because it’s not a maths lesson, doesn’t mean you can’t ask them the time, or ask what 6x7 is and how they know.

5. CPA all the way!!

Using consistent models and carefully chosen manipulatives help pupils to see the maths and make connections.

If you have a FSM child who is attaining below age related in their reading and writing, as well as maths, this will obviously impact lessons where they need to read and interpret the question. Using images and resources that are familiar will instantly help them to access these kinds of problems and overall make the maths much more achievable. And let’s be honest, CPA is good for ALL anyway!

6. Effective teaching and learning is what will make the difference.

We know that children don’t just ‘lack confidence’ in maths. They have grown to lack confidence due to a series of unsuccessful experiences. So, we need to try to build them back up again in a meaningful way. Telling them that it’s ok they aren’t good at maths because they’re great at PE is not overly helpful. Ensure work is initially pitched slightly below where they are working, so that they can whizz through a few questions and feel the buzz of being right. Then increase the challenge slowly but steadily throughout the lesson in small steps. Pre-teach concepts that are due to come up in the following week or introduce language beforehand. Whole class fluency is perfect for this if you don’t have the luxury of extra adult support.

7. Pre-empt behaviour

Touch base with your FSM children as soon as the independent work begins.

Don’t leave them to flounder for 10 minutes first, or else you might not get them back for the whole lesson. Remember why they do not have as much resilience. They are not waiting for help just to be annoying!

8. Fill gaps

We find that FSM pupils often have gaps in their maths understanding, which then hinders their progress.

This is inevitable really, when you remember that they may have had a time in their lives when things were tough at home, due to money being tight. Economic hardship is hard, even for the most loving of families. Perhaps their parents argued more, or they were more stressed generally and that can impact a child’s openness to learning. Therefore, it is our job to close these gaps. Quickly. That might be small group catch-up in addition to the maths lesson, but for the majority of pupils, it shouldn’t necessarily mean that they are regularly given work pitched lower than age related. Obviously, every child is different, but it is crucial that teachers have high expectations of what these pupils can achieve. They must have exposure to age related (and deeper) learning. Or else, what are they aspiring to?

9. Be resilient and patient

We usually talk about the children needing resilience, but when it comes to FSM pupils, often it is the adults that need it more. Feeling like you are repeating the same thing time after time is tiring. But necessary. The repetition is what is needed for learning to be retained. Be patient. You are trying to undo years of ineffective learning behaviours (zoning out, reliance on teacher, no confidence etc) so that is unlikely to change within two lessons.

10. Give status

In most classes, there is a superb calculator; a child who knows all their multiplication facts and is quick at mental calculation. So, when you ask a question, you know that their hand will shoot straight up. And they will be correct. And every time they are correct, their ‘advantage’ grows. This is what we need for our disadvantaged pupils. Actively seek opportunities where they can share and be accurate in public way, to build their status within the maths classroom.

Fluency sessions can be great for this because the content has been taught before, so if it’s pitched accurately, they should be able to offer a response. Check in with them while the class are busy solving problems to make sure they do actually have the right answer, and then ask them to share it. Sometimes we need to actively find out what they have written on their whiteboard, because they may not have the confidence to share it themselves. If you have children who hate to share whole class, you can still give status 1:1. Speak to them and offer genuine praise in a way that shows it’s what you expected of them all along because they are a mathematician, like every other child in the class.

With the economic situation in the UK as it is, it is likely that things will get worse before they get better. The rising cost of living is affecting all families, but those who were experiencing hardship previously will be finding things even more challenging. Unfortunately, we can’t really affect that. But we can affect what happens in the classroom for these children.

Dan Nicholls suggests that there are three key things we can do for disadvantaged pupils: Give status, foster a sense of belonging and fuel esteem. Couple that alongside a rich maths curriculum and effective teaching and we might just be able to make a difference for these pupils.

If you’re looking for support with primary maths teaching or subject leadership through in-school or remote consultancy, staff meeting or INSET sessions, please get in touch for further details.

Primary mathematics teaching and learning advisory services

Bibliography

Education & Skills Funding Agency, 2022. Guidance - Pupil premium 2022 to 2023: conditions of grant for local authorities. [Online]

Available at:

Gov.UK: Pupil premium 2022 to 2023: conditions of grant for local authorities

To keep up to date: Join our Primary Subject Leaders’ mailing list

To subscribe to our blogs: Get our blogs straight to your inbox